Korea remains: How are human remains identified?

- Published

The latest repatriated remains arrived in South Korea on the July 27, the 65th anniversary of the armistice that ended the fighting

Some families of the US Korean War dead have waited decades for closure about their missing loved ones, with the remains of an estimated 5,300 thought still to be scattered across North Korean territory.

On Thursday the remains of 55 people were transferred back - but how do you begin to identify decades-old remains?

Initial examination

CNN reports say that US officials planned to make a "cursory review" of what was being transferred over, external by the North Koreans, which was then photographed.

Experts will then look a bit more closely, examining any material evidence found alongside, such as uniforms and identification tags, for clues.

After a formal repatriation ceremony, the remains will then go to the Defence POW/MIA Accounting Agency lab (DPAA) in Hawaii - which describes itself as the largest anthropological lab in the world - where remains from servicemen from World War II, Korea and Vietnam are tested.

Repatriation of war dead has been done in stages - and has been a point of contention in US-North Korea relations

Experts there have admitted that 99% of the Korean War missing don't have DNA on file, so the process is multi-layered and complex.

Building a biological profile

Forensic Anthropologists can tell a lot from initial examinations of skeletal remains. Our bone appearance can give away indications about our ancestry, sex, age and height.

Because there are an estimated 33,000 coalition troops still unaccounted for in North Korea, there is no guarantee all of those transferred will even be US troops.

Doctor Helen Langstaff, a lecturer at the Center for Anatomy and Human Identification at the University of Dundee, says skull size is a key indicator of where in the world they could hail from.

She adds that pelvis size and shape is routinely used as an indicator of a skeleton's gender, with longer arm and leg bones measured to indicate a person's height.

"They take all this data about who is missing and start narrowing down the options," she says about the process.

Students pictured examining skeletal remains at the University of Dundee, where Dr Langstaff lectures

"If some of the missing are quite young, 18-20, then the body starts off with more bones that gradually fuse together to form the bones we'd recognise in an adult - that process might not be complete in some of them that are at that younger age bracket."

Personal identifiers

While biological identifiers are still quite generic, there are also other things in skeletal remains that experts can look for on the surface. This can include things like visible surgical implants or the appearance of healed injuries such as fractures which can be cross-checked with medical records.

A forensic odontology expert specifically looks at individual characteristics in dental remains - a common method of identification.

"You can also compare with information from dentists, who know what fillings they have and in what places," Dr Langstaff says.

The DPAA says it uses x-rays and even handwritten charts and treatment notes in their research process, but with decades-old identification, accessing records is a challenge.

DNA testing

DNA testing, itself only a couple of decades old, works by comparing unique genetic markers in two biological samples.

If there is no tissue is left on remains, mitochondrial DNA can be pulled from skeletal and tooth material by experts - but it is not a simple process.

Remains recovered in 2012 were identified as King Richard III centuries after his death down to "overwhelming evidence" including DNA analysis

Ideally DNA should be taken from areas of bone and teeth which haven't been in direct contact with contaminants such as soil. Outside influences such as burning can also affect the quality of the samples.

"You can get bones that are thousands of years old and are completely fine and you can get bones that have been in the ground for a matter of a decade," Dr Langstaff says.

"Depending on the soil they've been in, especially if it's acidic or something like that, then they can just be tiny little fragments that can be very fragile or crumbly."

If remains have been stored together, there is also the possibility of cross-contamination and mixing up of remains. This could mean every piece has to be tested separately, protracting the process.

Technological developments

Huge advancements have been made to the techniques of extracting, identifying and comparing samples in recent years.

This has in part been pioneered by the intensive effort in New York to identify victims from the 9/11 terror attacks.

The effort in New York is considered the most costly forensic investigation in US history

Tens of thousands of fragments of remains were collected at the site, but very few were recovered intact.

Identifying victims was then complicated by the remains having been mixed with other pulverised non-human remains as well as having been exposed to jet fuel, fire, water and other influences.

There still have only been 1,642 positive identifications of the 2,753 people killed there. But the latest came just on Wednesday, when a fragment was matched to 26-year-old financial worker Scott Michael Johnson.

Mark Desire, the assistant director of the office's department of forensic biology, told the New York Times that they had been able to identify Mr Johnson using a new technique, external which involved using metal ball bearings in the process where bones are pulverised to extract DNA.

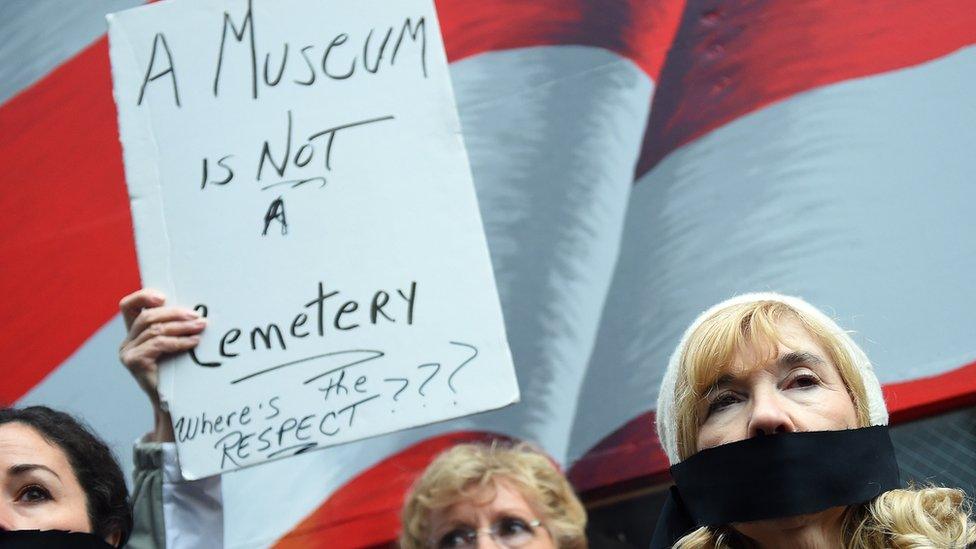

Most of the unidentified remains are now held at a repository at Ground Zero, a decision which in 2014 irked some families of the dead

The sample size is said to have been so limited that scientists had to replicate it by using enzymes to spark a polymerase chain reaction to make it bigger, so the DNA was usable for identification. After three processes, the sample was big enough to cross-check the DNA to find Mr Johnson with the thousands of records on file.

Identifying war dead is made difficult because of there is no such database and decades on immediate family members may be harder to find.

The DPAA office says it uses mitochondrial DNA testing in most of its identification, with sequences compared with family reference samples taken from maternal descendants.

These are not perfect for identification though - the organisation says that separate evidence must then be used to support the genetic sampling, external before going through peer review processes and external review by independent experts.

- Published21 February 2012

- Published12 June 2018

- Published27 July 2018

- Published7 August 2017