Climate change: Protecting the poor from green taxes

- Published

President Macron says he is 'partly responsible' for the 'insufficient response' to the yellow vest protests

As President Macron caved into the yellow vest fuel tax protests, President Trump was triumphant.

The French humiliation showed people rejected the sort of carbon taxes supported by the UN’s climate deal, he tweeted.

Of course it’s more complicated than that, because it depends on what sort of carbon taxes and how they are imposed.

Green economists say carbon taxes are a good idea - but they insist that governments must protect the poor from the side-effects.

Why are the poor vulnerable to green taxes?

It’s a question of disposable income. If a government imposes a flat tax on motor fuel as Mr Macron did, that hits the poor hardest because it eats their disposable income.

The fuel rises were doubly galling for the yellow vests in their suburban and rural homes because they can’t rely on good public transport like rich city slickers do.

The tax was supposed to help reduce carbon emissions

The UK faced a less violent protest in 2001 when the past Labour government tried to notch up a petrol tax rise with its annual “fuel tax escalator”.

The policy had succeeded in suppressing the relentless rise in traffic, and prompted more fuel-efficient vehicles.

But the Conservative opposition leader William Hague quipped: “If you’re on an escalator you have to know when to get off!”

So how can the poor be protected?

Academics have figured out over the years how to protect the poor from green taxes, but Mr Macron appears to have missed their research, or ignored it.

His fuel tax took from people struggling with living costs, and diverted the proceeds to wind farms instead.

A very different Robin Hood policy in Australia deliberately re-directed carbon taxes to help the worse-off.

It took the $5bn Australian dollars ($3.6bn; £2.9bn) of annual profits from a carbon tax on industry and diverted it to the poor by introducing lower income taxes and higher welfare payments.

Most households - and just about all poor households - were better off as a result, whereas richer households bore most of the costs, according to Prof Frank Jotzo from the Australian National University in Canberra.

Why are green taxes on the rise?

Pollution imposes costs on society, and most governments accept that people and businesses should pay for the pollution they cause.

With climate change, for instance, carbon emissions are likely to damage crops; increase health care costs from heatwaves; and droughts; make flooding worse; inundate homes from sea level rise - and much more.

As a result, the World Bank says, carbon taxes have been introduced in 40 countries, external and more than 20 cities, states and provinces. Many more schemes are in the pipeline.

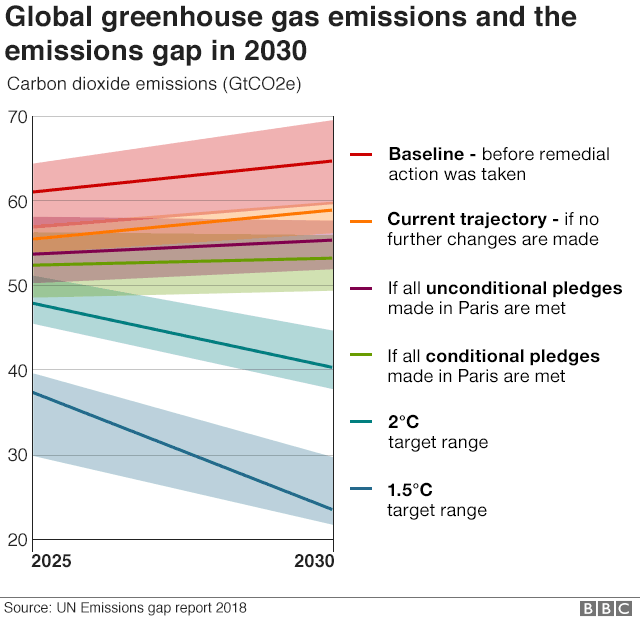

Together they cover about 13% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions, and are, according to the Bank, the cheapest way for nations to cut emissions because they allow businesses to choose when and how to invest in clean technology.

It says carbon prices stimulates innovation and fuels new low-carbon drivers of economic growth.

So are green economists cursing Mr Macron?

Environmental economists will be appalled that the Macron policies have made carbon taxes more politically toxic just as governments need good solutions to climate change.

World-leading research into the social impacts of green taxes has been done at University College London by Prof Paul Ekins.

He says governments must think hard about protecting the poor before they introduce taxes.

Even then, he says, ministers may have to devise special measures to support small groups of households faced with higher bills because - say - they have a sick family member who needs to be kept very warm.

Do people support green taxes?

There’s one final problem… green taxes are complicated and can be hard to communicate.

In Australia, for instance, the coal industry has a very loud voice in public debate. And it supported the claim of the right-wing politician Tony Abbott that the carbon tax was: “A big fat tax on everything”.

The tax was scrapped, even though Prof Jotzo says the poor were actually better off since it was imposed.

People believed the rhetoric rather than the evidence of their bank accounts, he says.

"The Australian experience shows that governments need to design environmental policies to leave lower income people better off, and then also to explain this to the voters," Prof Jotzo says.

"Just doing the right thing is not enough, you need to also cut through the noise and misinformation... Mr Macron's team clearly did not study the lessons from the Antipodes."

Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin, external

- Published27 November 2018

- Published3 December 2018

- Published8 December 2018