The boy who survived a plane crash in Alaska

- Published

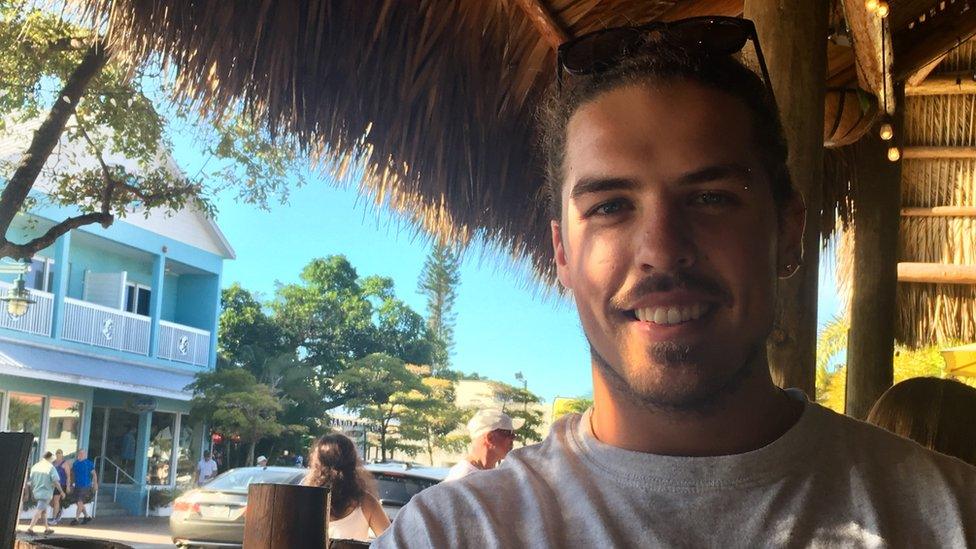

Willy Phillips Jr was 13 years old when he survived a plane crash that killed his father in 2010. Almost nine years on, he explains how he is still coming to terms with how he survived.

The weather in Alaska on 9 August 2010 was awful - raining and foggy. The group had planned a fishing trip, travelling by plane, but Willy says "the likelihood of us getting out was not very high".

Willy was in Alaska with his father William "Bill" Phillips, and former US senator, Ted Stevens. Bill had previously worked for Senator Stevens, who had represented Alaska for more than 40 years, and was known by many in the state as "Uncle Ted".

"After an hour or so we finally got the heads up that we would be able to make it out," Willy remembers, "so that was pretty exciting. So everybody is running around and getting their things together".

They would use a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter, an amphibious float-plane. Willy had been on it before and knew how it worked. But this time for some reason he didn't put his seatbelt on.

"I was sitting on the window seat and I was dozing in and out of the reality around me.

"One of the last things I remember before the accident was that there was a bunch of rain on the window, and I remember sitting there and there was a big drop of water that was snaking its way down the window. Right as it got to the bottom - that's when I fell asleep."

The wreckage of the plane on an Alaskan mountainside

At about 14:30 Alaska Daylight Time the plane crashed into the side of a mountain. The weather was bad, visibility was poor. But the exact reasons for the crash are still unknown.

An investigation by the US National Transportation Safety Board couldn't say for sure what happened. It speculated that the pilot, who was one of five people killed, may have fallen asleep or had a seizure, but there was no direct evidence to support these theories.

Willy says he thought it had been a dream: "I was sitting there for probably an hour or so. Every five minutes I would try to fall back asleep and then I'd wake up and then I'd think OK maybe I'll try again. And I would close my eyes and then open them up again and I'm still in this place."

'I wasn't in my seat'

Eventually he realised he had to move.

"I wasn't in my seat. Had I actually been wearing my seatbelt I could have been in a much worse situation. Because I ended up being in the cockpit of the plane. I sustained most of my injuries making impact with the front of the plane as we had come into contact with the mountain.

"Right in front of me were a few broken bushes and glass everywhere. I ended up pretty much sitting on the lap of the person who'd been in the co-pilot's seat for the duration of that flight. I was looking at a 50% gradient on the mountain."

It's still not clear what caused the plane to crash

There were nine passengers and crew on the plane. Five lost their lives.

"You kind of assume the worst at this point," Willy says. "I heard some rustling around and some voices so I definitely had some hope that I could be going to an area full of people.

"I went around the side of the plane... right down the side of [the] mountain and kind of made my way to the spot where I was originally sitting. And it was actually quite morbid.

"It was just a group of lifeless people and then other people who were just scattered among them, who were alive at that point."

Willy says what he'd learned from his father was key in keeping him calm.

"He had a role in keeping my head level," he says. "For my entire life he had taught my brothers and I that by getting overly frustrated or anxious in a moment doesn't help the resolution. My first instinct was to be the calmest there. I didn't really see another option, it didn't feel right to talk about how bad a situation we were in, that didn't seem helpful to anybody."

Willy saw one of his father's best friends, who had survived: "He was one of the first people to bring me down to earth a little bit. He was like 'Willy you know we're going to need your help, but do you know that your father is dead?' But I knew right then was not the time to have this moment of breakdown. It was something I was told then, but not something I came to terms with until we got out of there."

Treacherous conditions

As soon as it was reported that the aircraft hadn't landed as scheduled, other pilots launched a search. But Willy says the authorities assumed the plane had crashed and everybody on board had died. Nobody was looking at a rescue operation.

"The focus was on getting us out the next day because with no survivors and the weather not good, it didn't make sense to rescue a plane full of bodies," he says.

The wreckage of the plane was found at 18:30 local time on a 40-degree slope in the mountainous Dillingham region of Alaska.

"I could just hear very faint fluttering of a helicopter somewhere in the distance so I scrambled out of the fuselage of the plane. I had on a white sweatshirt and I started throwing that around and waving my hands around. I think it was at that moment that we turned from a 'recovery the next morning' to a 'rescue immediately'."

Within half-an-hour of Willy's white sweatshirt being spotted, rescue teams were on the ground - a doctor and a handful of local responders were airlifted in to help the survivors. But with the weather conditions deteriorating, it was seen as too treacherous to get the casualties out that night, and the full scale rescue didn't start until the next morning.

Willy had multiple injuries on his left side, including a broken ankle requiring 13 surgeries, plus injuries to his shoulder, wrist and nose.

As he says, "It's been a long process".

Willy Phillips was in hospital for 10 days in Alaska before being transferred to Washington

The crash was front page news across the US. One of America's longest serving politicians, Senator Ted Stevens, had died. Statements poured in commemorating the late senator, including from President Obama, who said: "Michelle and I extend our condolences to the entire Stevens family and to the families of those who perished alongside Senator Stevens in this terrible accident."

For Willy and his family, the news coverage meant recovery was even harder: "It complicated things when there would be reporters showing up at the end of our driveway or coming and knocking on our front door. Any time my mum went to the grocery store she would be accosted by somebody. It was years of somebody trying to get a story. "

It's been almost nine years since the crash, and Willy is philosophical.

"It's one of those things that had to happen to somebody - it happened to me. It was obviously an unfortunate thing, but exposed me to so many finer idiosyncrasies of life that I don't think I would ever have had an appreciation for in the same way... Every day when I wake up I think this is so infinitely better to waking up on the side of that mountain so today is probably going to be a pretty good day."

'Crippling anxiety'

Willy is currently studying environmental science and in particular, water.

"I used to have this crippling anxiety every time it would rain because that was the last thing that I remember when everything was normal. The last thing I remember before waking up on the mountain was seeing the rain on the side of that window and so for years it scared the hell out of me. It would rain and I would feel it raining and I would just kind of collapse."

He says he's since taken rain, which he called his biggest weakness, to be his biggest source of motivation.

"Maybe I think about my Dad when I do that stuff. I learn from him every single day. I think about how my outward actions and expressions are influenced by him and I think I take after him quite a bit.

"Alaska and the natural environment were things that he always had an appreciation for and he definitely passed that down to me, and that's probably part of my reason in being so invested in what I study.

"There's something to it that I just can't get enough of."

Listen to Emma Barnett's full interview with Willy Phillips on BBC Sounds.