What are vaccines, how do they work and why are people sceptical?

- Published

Vaccines have saved tens of millions of lives in the past century, yet in many countries health experts have identified a trend towards “vaccine hesitancy” – an increasing refusal to use vaccination.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is so concerned that it has listed this trend as one of the 10 threats to global health in 2019.

How was vaccination discovered?

Before vaccines existed, the world was a far more dangerous place, with millions dying each year to now preventable illnesses.

The Chinese were the first to discover an early form of vaccination in the 10th Century.

Eight centuries later, British doctor Edward Jenner noticed how milkmaids caught mild cowpox, but rarely went on to contract the deadly smallpox.

In 1796 Jenner carried out an experiment on eight-year-old James Phipps.

The doctor inserted pus from a cowpox wound into the boy, who soon developed symptoms.

Once Phipps had recovered, Jenner inserted smallpox into the boy but he remained healthy. The cowpox had made him immune.

In 1798, the results were published and the word vaccine - from the Latin 'vacca' for cow - was coined.

What have been the successes?

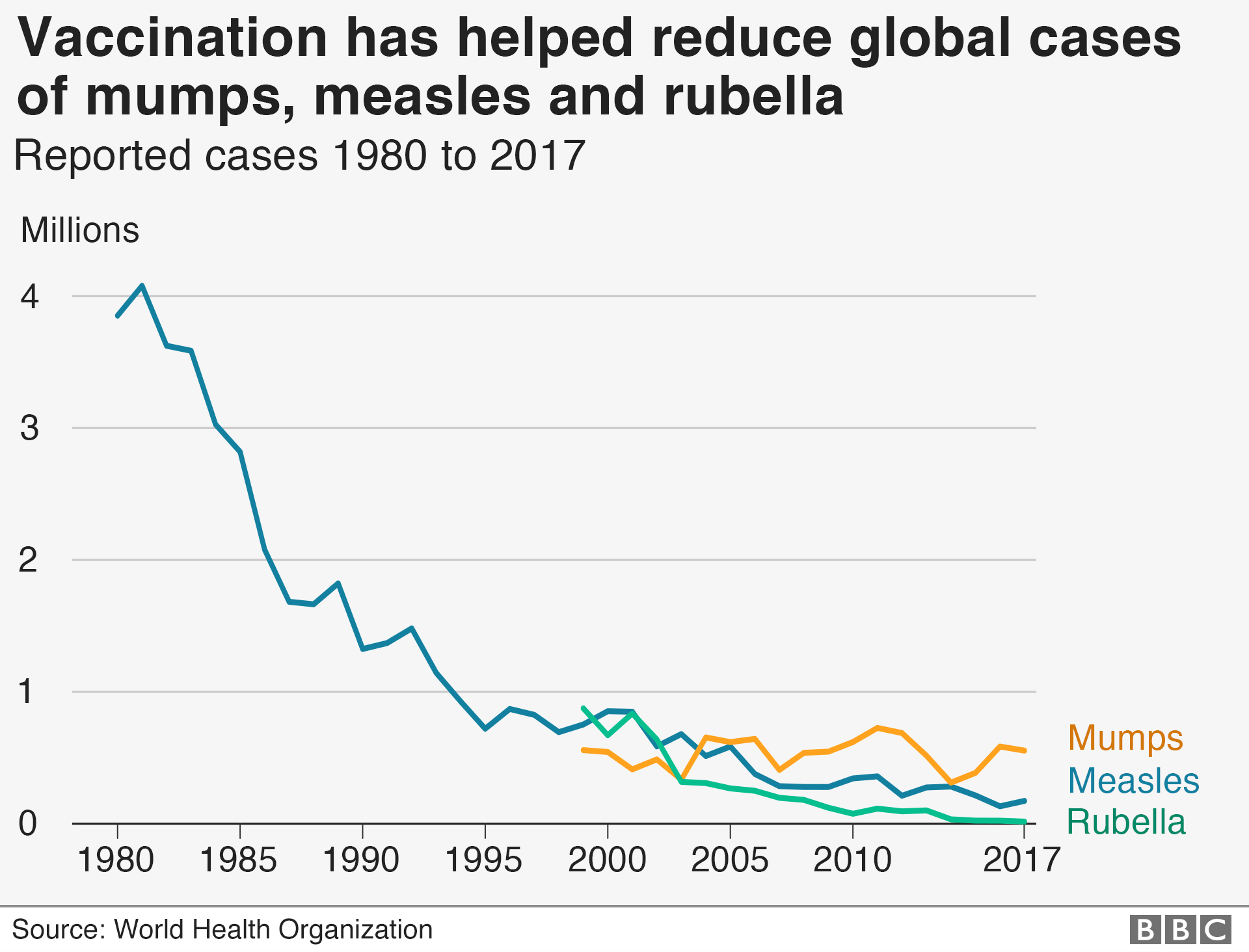

Vaccines have helped drastically reduce the damage done by many diseases in the past century.

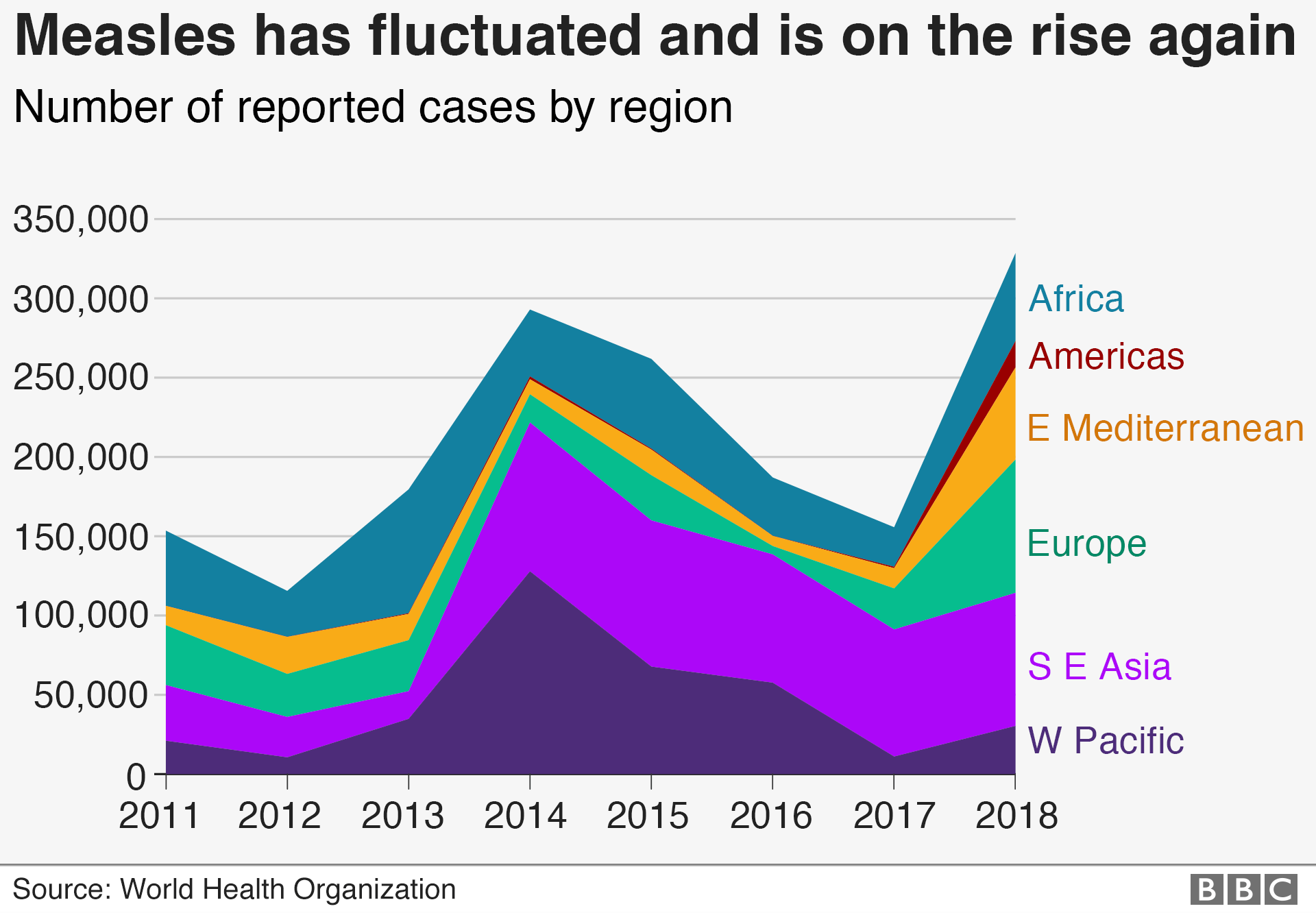

About 2.6m people were dying from measles every year before the first vaccination for the disease was introduced in the 1960s. Vaccination resulted in an 80% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2017 worldwide, according to the WHO.

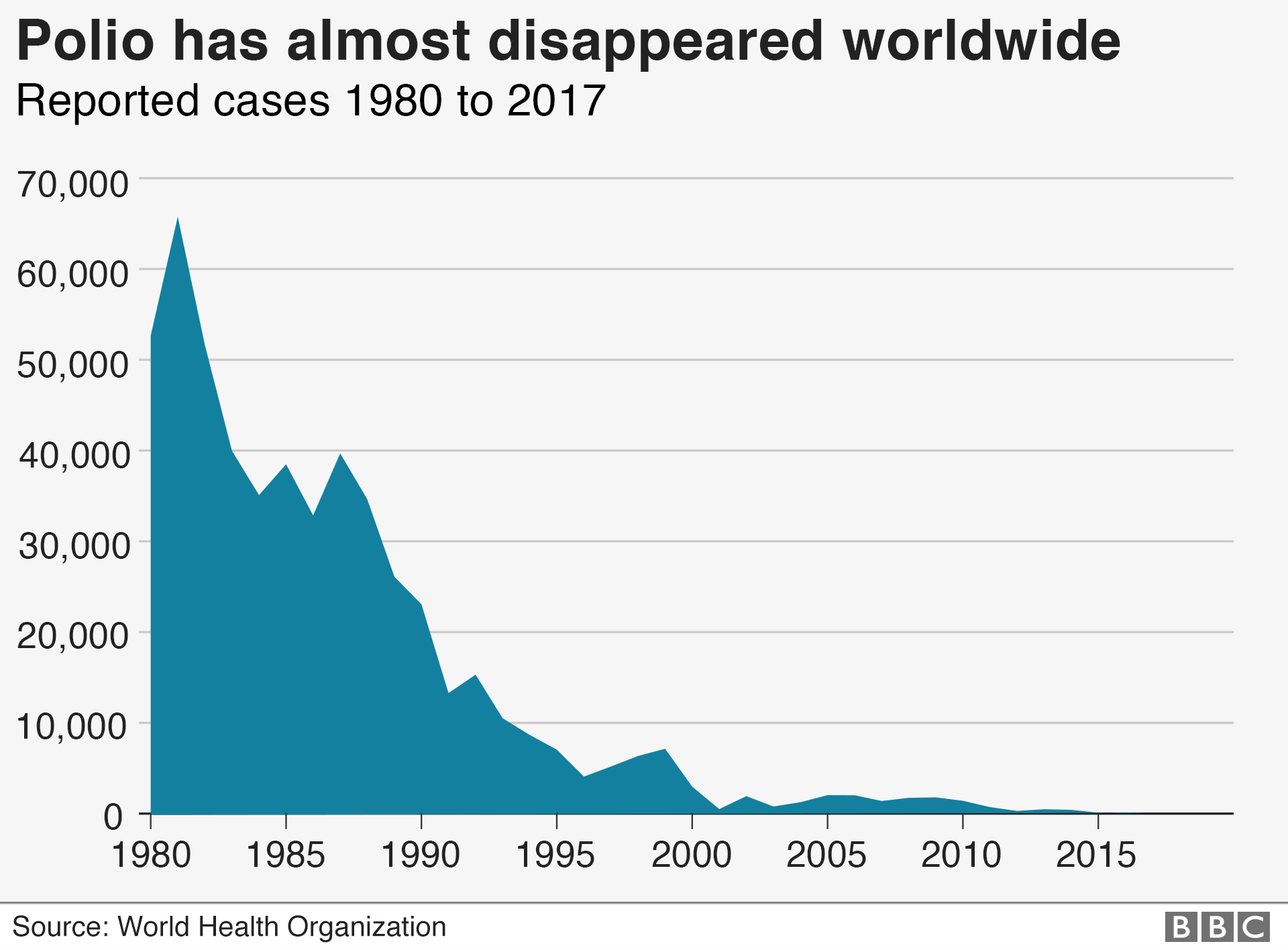

Only a few decades ago, paralysis or death was a very real concern as millions fell victim to polio. Now polio has almost disappeared.

Why do some people refuse vaccination?

Suspicion of vaccines has been around almost as long as modern vaccines themselves.

In the past people were sceptical for religious reasons, because they thought vaccination was unclean, or because they felt it infringed on their freedom of choice.

In the 1800s so-called anti-vaccination leagues popped up across Britain, pushing for alternative measures to fight disease, such as isolating patients.

In the 1870s, the first anti-vaccination group in the US started after a visit by a British anti-vaccination activist, William Tebb.

One of the key figures in the recent history of the anti-vaccination movement is Andrew Wakefield.

In 1998, the London-based doctor published a report falsely linking autism and bowel disease to the MMR vaccine.

Even though his paper was discredited and Wakefield was struck from the medical register in the UK, there was a drop in the number of children vaccinated after his claims.

The issue of vaccines is being increasingly politicised too.

Italy’s interior minister Matteo Salvini has allied himself with anti-vaccination groups.

US President Donald Trump, without evidence, appeared to link vaccinations to autism, but has recently urged parents to get their children vaccinated.

The biggest global study of attitudes to immunisation, conducted by the Wellcome Trust in 2019, suggested that distrust of vaccines was highest in Europe, with France the most sceptical.

What are the risks?

When a high proportion of the population is vaccinated it helps prevent the spread of disease which in turn provides protection for those who have not developed immunity or who cannot be vaccinated.

This is called herd immunity and when it breaks down there is a risk to the wider population.

Last year in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, USA, fliers were distributed wrongly claiming links between vaccines and autism.

That same community has been at the centre of one of the largest outbreaks of measles in the US in decades.

England’s most senior doctor warned last year that too many people were being fooled by misleading information about vaccines on social media, and US researchers found that Russian bots were being used to sow discord online by posting false information about vaccines.

The proportion of the world’s children who receive recommended vaccines has remained unchanged at 85% for the past few years, according to the World Health Organization.

The WHO says vaccines continue to prevent between two and three million deaths worldwide every year.

The biggest challenges to vaccination, and the lowest rates of immunisation, are in countries with a recent history of conflict and extremely poor healthcare systems, including Afghanistan, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

But the WHO has also identified complacency as a key issue in developed countries; put simply people have forgotten the harm a disease can do.

If you cannot see the interactive content above click here., external

Produced by Roland Hughes, George Wright, David Brown, Tom Francis-Winnington and Sean Willmott

- Published29 April 2019

- Published29 November 2018

- Published5 March 2019

- Published1 November 2018

- Published24 January 2019