What will the end of oil dependence mean for geopolitics?

- Published

Solar power is one form of renewable energy that is replacing fossil fuels

If you want to understand the revolution taking place in renewable energy, come to a power station called Gemasolar in southern Spain.

Here, in the dusty plains of Andalusia, they have worked out how to generate solar power 24 hours a day.

Yes, you can read that sentence again. At Gemasolar they create electricity even when the Sun is not shining.

They have rigged up more than 2,500 huge mirrors on hydraulic mounts that follow the Sun's passage through the sky.

The mirrors - each about the size of half a tennis court - reflect the Sun's rays to one central point, the top of a 140m (459ft) tower, where molten salt is heated to almost 600C. This liquid salt is carried down the tower to where it heats the steam that powers a turbine.

And here's the trick: not all the salt is used at that point. Some is stored in huge tanks and used later when the Sun has gone down. So long as the Sun shines every day, the plant can generate power 24/7.

I tell you this not just as an illustration of how fast renewable technology is changing - this particular innovation is not that new - but also as an example of how electrified our energy is set to become.

The expansion of electric vehicles is predicted to accelerate significantly, external, to a point when it will become the norm rather than the exception.

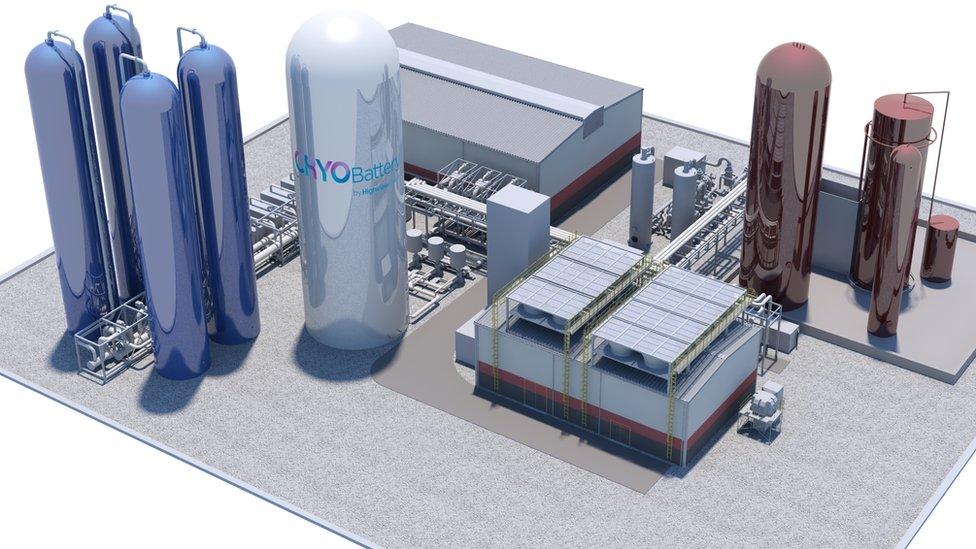

Battery technology still has far to go but many scientists and businesses are competing to find ways of storing electrical power that is lighter and longer-lasting. Already some electrically powered passenger aircraft are in production. How long before ships can be powered by batteries rather than fuel oil?

The plane that can fly 600 miles on batteries alone

The obvious and much-contested question is when this renewable revolution will reach its peak and whether it will come in time to protect the planet from global warming. That is not something I am qualified to answer.

What interests me is a separate question: what impact might this new technology have, not on the world's climate, but its politics?

What happens to the global balance of political power when so many countries no longer need to buy so much oil and gas? This is a question that Adam Bowen and I have sought to answer in a documentary for the BBC World Service and Radio Four.

For more than a century, nations that had oil and gas had power, literally and politically. Wars were fought over the stuff.

The Iraqi military set Kuwaiti oil fields on fire after their retreat in 1991

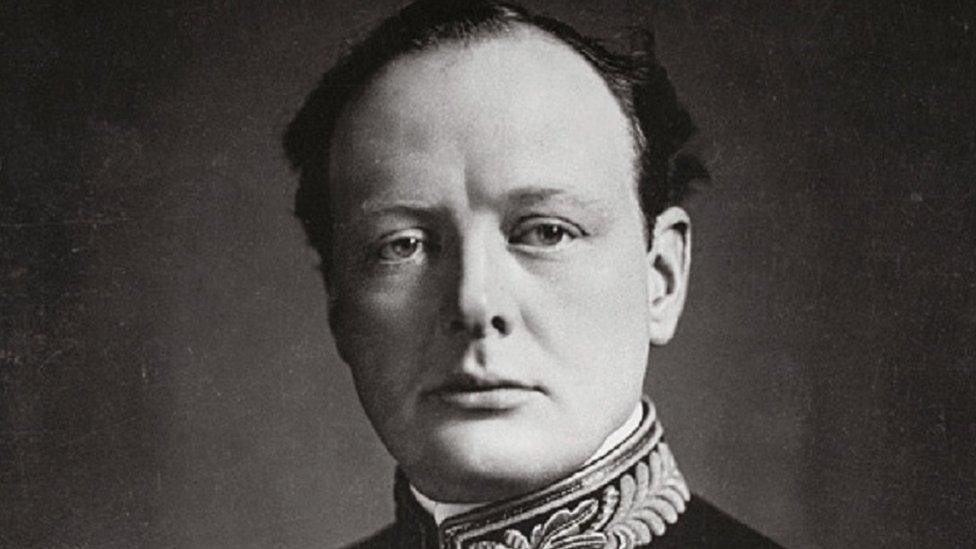

It all began before the World War One when Winston Churchill - as First Lord of the Admiralty - converted the British navy from Welsh coal to imported oil.

To secure British access to that oil, the future British prime minister bought a controlling stake in the Anglo Persian oil company, the forerunner of BP, in what is now Iran.

From that moment, much of the history of the 20th Century can be seen through countries' pursuit of hydrocarbons, from Adolf Hitler's attempts to secure the Baku oil fields to Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait to last September's drone and missile attack on Saudi oil facilities.

Countries with oil and gas used their monopolies to sell the stuff for huge profits; those countries which relied on it spent much blood and treasure defending their access to it.

Churchill - pictured here in 1914 - oversaw the Royal Navy's transition from coal to oil

The question is how much the renewable revolution might change this geopolitical equation. How much influence will be lost by some of the world's big fossil fuel producers, in the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere?

Might there be more regional conflict as these countries fight over an ever-decreasing share of the hydrocarbon energy market? And what might happen to these countries internally if they lose their main source of revenue?

Often these are nations have huge state-led economies, with many workers employed by governments, with youthful populations accustomed to cheap fuel.

There is little consensus over when the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy will take place. There are many different predictions about when global demand for oil will peak and fall away but the planners at Shell recently forecast it could happen as early as 2025, external.

So some oil-producing countries are playing safe and preparing for the moment when they can no longer rely on oil. They are looking to diversify their economies and find other sources of energy.

But other countries are more sceptical, trusting that demand for their oil and gas will last for some time.

Some of these countries stand accused of talking about diversification but doing little about it. The potential consequences of this are becoming an increasing source of concern.

Protests over a fuel price hike recently erupted in Iran

This is what Prof Paul Stevens, distinguished fellow at the UK foreign affairs think tank Chatham House, told the BBC: "The oil producing government gets revenue; if that revenue falls or disappears, the government is no longer able to sustain the non-oil sector, which means you will have rising unemployment, you will no longer be able to pay subsidies to keep your population happy.

"Many of the large oil and gas exporters are what might politely be described as politically unstable. So the faster the transition [to renewables], the greater the fall in gas and oil revenues, the more disruptive it is going to be and so you are looking at potentially a large number of failed states."

This is what Tom Burke, chairman of the E3G environmental think tank and a former UK government adviser says: "If you can't deliver food, energy and water security, as we have seen across the Middle East, it is pretty difficult to deliver internal stability. Urban populations, when you fail to meet their expectations, riot. You could have the basic structures of the state fall apart.

"But much more than that, when people riot or look like they might riot, what tends to happen in those situations in countries is they seek foreign adventures in order to distract people from their unmet expectations."

Saudi Arabia's Khurais oil processing plant was attack in September, causing global tensions

So just imagine a currently stable oil-producing country in the Gulf that suddenly becomes a failed state. Not only would this be a disaster for the country itself, but it could also have huge implications for the world.

Failed states often become the homes to extremist violence - think Syria - and they often produce mass migration.

This potential disruption might not be confined to the Gulf. Russia is one of the biggest exporters of oil and gas in the world. Its economy and its government depend hugely on the revenues this brings in. Little wonder that President Putin describes the development of "green technologies" as a one of the "main challenges and threats" to Russia's economic security, external.

The Russian economy is reliant on oil and gas revenues

Many Russians remember that falling oil prices contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union. But the current government is investing little in alternative renewable energies. If one day the world needs to buy less Russian gas, that could have a huge impact on the stability of the Russian state and could transform its relations with Europe.

There are other potential sources of tension and conflict in a world of clean energy.

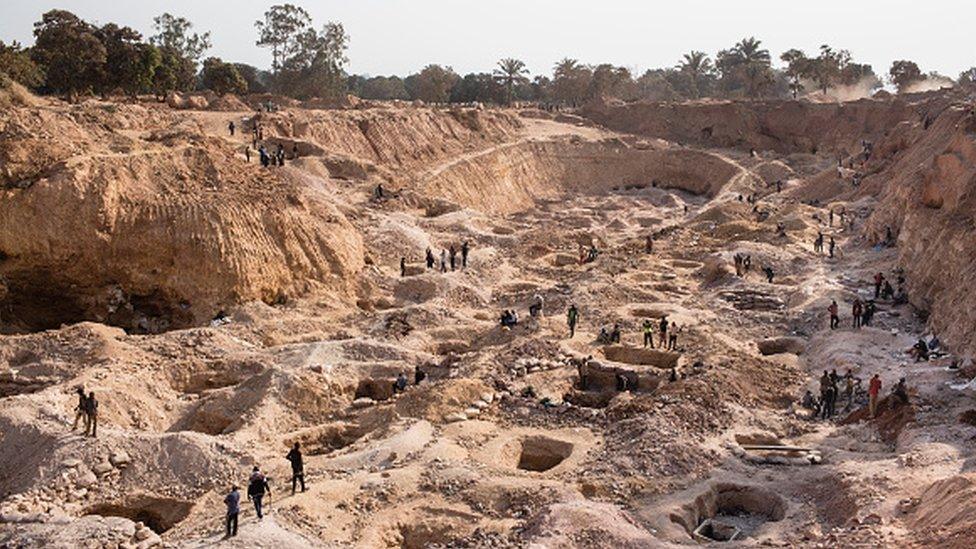

There could be a race to secure access to minerals such as cobalt and lithium which are vital for batteries and can be rare. Much of the world's best cobalt is located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) which has a history of instability and poor governance.

At the same time, the new so-called super grids through which electricity will flow between countries will be more vulnerable to cyber-attack.

Cobalt, a vital mineral needed for the production of rechargeable batteries, is a valuable commodity

An interesting question is how environmental campaigners should respond to the political risks involved in the move towards renewable energy.

Should those potential downsides be taken into account or is the need to protect the world from climate change so paramount that all other considerations are secondary? How might public opinion be affected if reducing global warming meant more terrorism and migration?

These, of course, are some of the worst-case scenarios. There are many potential positives.

When the transition to renewables takes place, countries that were previously energy dependent will be able to produce their own power. One of the advantages of renewables is that many more countries have the ability to generate clean energy.

Solar panels are becoming more common in domestic settings

Some countries with lots of sun, wind or tide could not only become self-sufficient but could also export some of their energy via huge so-called interconnectors. There may be something of a peace dividend: if the world no longer needs so much oil passing through the Strait of Hormuz each day, then perhaps they will not need such large armies and navies to defend it?

To a large extent, the geopolitics of energy may cease to be so significant. As Prof Stevens says, people will still find things to kill each other over, such as food and water.

But energy, maybe not so much.

The World Turned Upside Down is on BBC World Service on Friday, 3 January and Saturday, 4 January. It will also be broadcast in two parts on BBC Radio 4 on Sunday, 5 January and Sunday, 12 January. It can also be heard on the BBC Sounds app.

- Published25 November 2019

- Published3 July 2019

- Published22 October 2019