Soleimani attack: What does international law say?

- Published

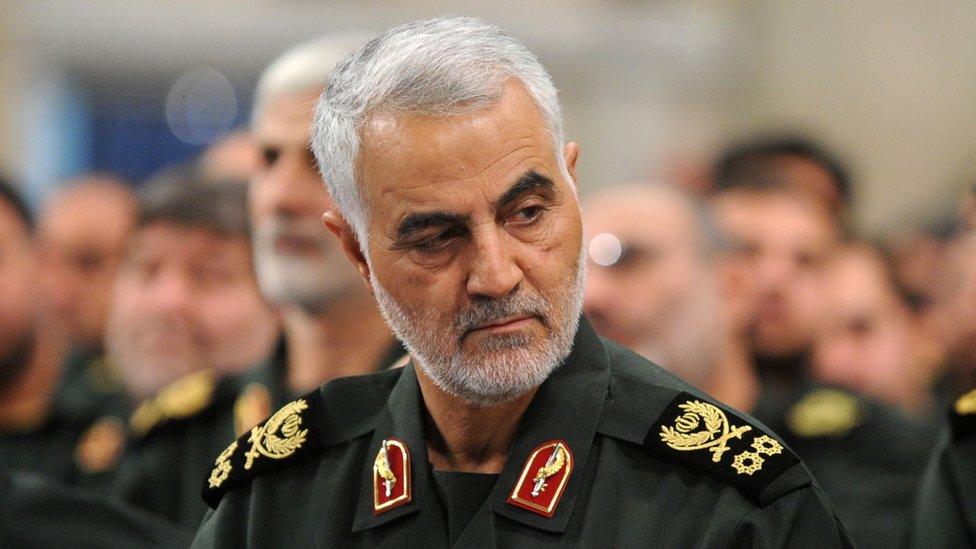

President Trump said Soleimani was plotting imminent attacks on American diplomats

US President Donald Trump ordered the drone strike that killed Iranian military commander Qasem Soleimani in Iraq but what are the legal grounds for this course of action?

The US said: "This strike was aimed at deterring future Iranian attack plans."

So, what are the key issues when considering its legality, according to international law?

What does the law say?

The relevant law in the UN Charter allows for a state to act in self-defence "if an armed attack occurs".

But this definition tends to be interpreted by governments, say legal experts.

"In the Soleimani case, the US is claiming it acted in self-defence to prevent imminent attacks, a category of action which, if in fact true, is generally seen as being permissible under the UN Charter," says Dapo Akande, professor of public international law at Oxford University and co-director of the Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict (ELAC).

But Agnes Callamard, UN special rapporteur on extra-judicial killings. has tweeted about the strike saying "this test is unlikely to be met".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

A 2010 UN report on "targeted killings", external said there was a weighty body of scholarship that viewed the self-defence argument as having the right to use force "against a real and imminent threat when the necessity of that self-defence is instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation."

The initial US Department of Defense statement, external omitted the word "imminent" and said the strike was aimed at deterring future Iranian attacks and that Iran's top military leader Soleimani was "actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region".

In later statements, US officials including President Trump said Soleimani had been plotting "imminent attacks".

Elizabeth Warren, a Democratic Party candidate for the US presidency, said: "The administration cannot keep its story straight."

So what evidence is there of planned attacks by Iran?

The legality of the strike under international law may well depend on the US providing evidence of those future attacks, according to Mr Akande.

The US government has not yet shared details publicly, but the administration has said intelligence has been shared with key figures in the US Congress.

Asked by a journalist on 7 January for more details about imminent threats, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo noted the incidents leading up to the strike, but did not provide any evidence of impending attacks.

There are other justifications it has used in the past, according to Dr Ralph Wilde, an expert in public international law at University College London.

"Since 9/11 the US has taken a view that self-defence can be justified to prevent more longer-term attacks. When the attack is being planned, but is not imminent. The Obama administration used this argument to justify drone strikes."

Mourners packed the streets in Tehran - and Iran's supreme leader wept as he led prayers

And what about the issue of consent?

The other issue is whether the US had consent from Iraq to carry out the strike there.

Iraqi MPs reacted angrily and passed a non-binding resolution calling for US troops to leave the country. The Iraqi government has called it a "brazen violation of Iraq's sovereignty".

US forces had been invited into Iraq to fight the Islamic State group and to train Iraqi forces.

The US might argue this invitation constituted some form of consent, giving them a right to protect their interests and personnel inside Iraq.

But Mr Akande argues that, in practice, the terms of the agreement to host US forces would not stretch to carrying out an attack like this.

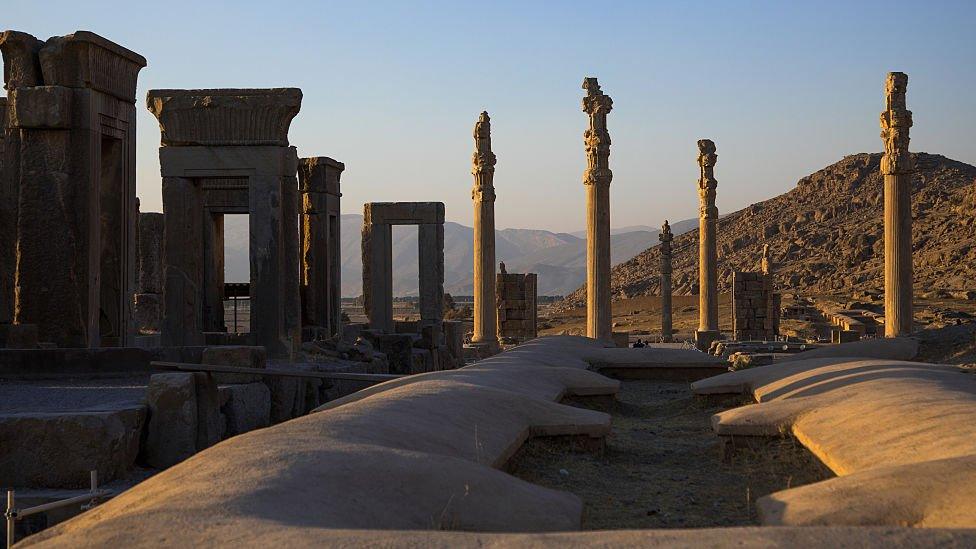

Persepolis is one of Iran's most famous cultural sites

Can you target cultural sites?

On Sunday, Mr Trump tweeted, warning the US would target sites that were "important to Iran and the Iranian culture" if American assets were hit.

The Iran Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif said an attack on a cultural site would amount to a war crime.

Trump's threat "shows callous disregard for the global rule of law", said Andrea Prasow of Human Rights Watch.

The US government insisted it would behave lawfully.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But an attack on a cultural site would violate several international treaties.

The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property safeguarded cultural sites in the wake of the destruction of cultural heritage sites during World War Two, and was signed by the US.

In 2017, the UN passed a resolution in response to the Islamic State attacks which condemned "the unlawful destruction of cultural heritage, including the destruction of religious sites and artefacts".

The US was among the harshest critics of the IS destruction of historic site of Palmyra in Syria in 2015, as well as the Taliban's demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001.

In 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) convicted someone for the destruction of cultural heritage for the first time, after an extremist linked to Al-Qaeda destroyed religious artefacts in Mali.

The US is not part of the ICC but it is a signatory of other agreements to protect cultural property and any attack would represent a significant reversal.

- Published3 January 2020

- Published8 January 2020

- Published6 January 2020

- Published6 January 2020

- Published3 January 2020

- Published3 January 2020