Coronavirus: Five things the military can do during pandemic

- Published

The Grenadier Guards are now taking their posts at the Palace without the usual music and ceremony

"They're changing Guard at Buckingham Palace…" begins the famous poem by AA Milne, creator of the much-loved children's character, Winnie the Pooh.

But it's not usually like this. The Grenadier Guards are now taking their posts at the Palace without the usual music and ceremony.

It's what's known as "an administrative Guard mount"; used usually when there is heavy rain or a timing conflict with another important event. Now it's part of the government's social distancing policy - an effort to avoid drawing spectators together.

And this is the way the guard will be mounted for the foreseeable future.

It highlights the measure of continuity in the armed forces' role. Their primary job is to protect the country and, if necessary, to go into combat in a full-scale war.

But now in many countries around the world, the armed forces are being called upon in increasing numbers to assist in a very different kind of war - the campaign against the coronavirus pandemic. And it is a trend that is likely to continue as more and more service personnel are mobilised.

In the UK, the government is advising its citizens to adhere to a social distancing policy

Already traditional military duties are being halted. In Britain for example, the training of recruits has stopped; international exercises - like nato's Defender-Europe 20, which was to have seen the largest deployment of US forces to Europe for many years - have been significantly curtailed.

Even ongoing operations are being suspended and the numbers of troops deployed significantly reduced. A good example is the international effort in Iraq to train and support its armed forces.

In many societies, when the military goes onto the streets it is a sign of political instability. Different cultures, different countries react to the heightened visibility of the armed forces in different ways.

But even in the most stable democratic societies, like those in Western Europe, the deployment of troops is not so unusual. Flood or disaster relief often brings small number of soldiers, sailors or airmen into closer proximity with the public.

In several EU countries the rising concerns about terrorism have made the presence of armed military patrols at railway stations and other public locations more commonplace.

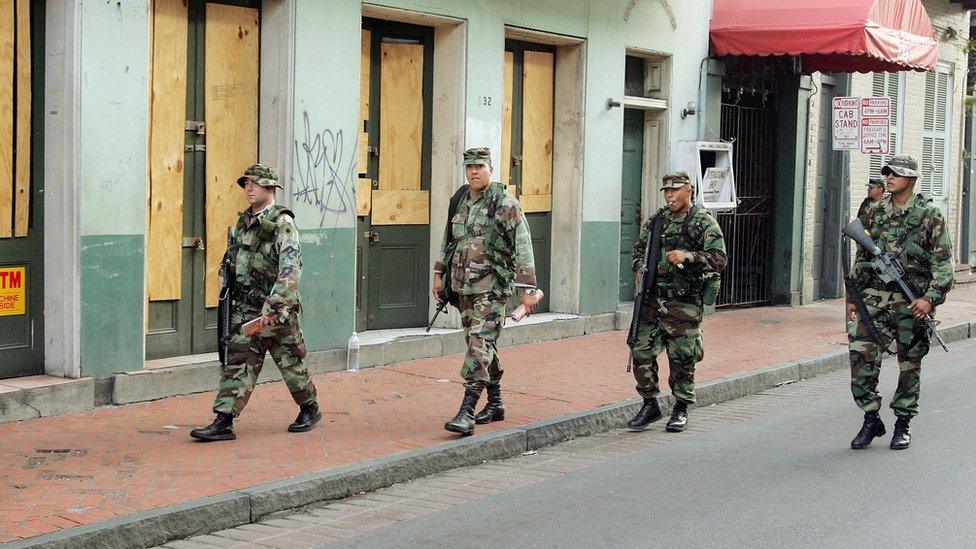

In rare cases there can be very sizeable deployments. After Hurricane Katrina struck the US Gulf Coast in 2005 the Department of Defense deployed some 70,000 personnel - part of a wider national effort, which, at the time, was much criticised for its disorganisation.

Soldiers were called up to help after Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans in 2005

But what is likely to happen as this pandemic continues is of a totally different order. The head of Britain's armed forces, General Sir Nicholas Carter, has spoken of the need for their "collective posture to be on an operational footing by mid-April". Already some 20,000 troops are on stand-by.

So what is it that the military can provide? Here are five key areas where the armed forces can help.

People

The armed forces represent a significant pool of trained, disciplined, and motivated men and women with a vast array of skills. They are resourceful, mobile and able to set up and operate quickly at short notice.

They have a range of facilities - bases, airfields and so on - some of which might eventually be used for a variety of tasks.

Medical support

The military clearly has highly-trained, though often limited numbers of medical personnel. Few countries' armed forces have the resources of the US, where the Pentagon has already agreed to contribute five million respirator masks and 2,000 ventilators from its stocks to the health system.

The US Navy is mobilising its two hospital ships, the USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort. These are effectively huge floating wards that while not suited to combating an infectious disease, can help to relieve at least a small part of the pressure on facilities ashore. They will take some time to get ready though and may only be deployed in the larger port cities.

The US Navy has mobilised two of its hospital ships including the USNS Mercy

The medical facilities that the military can bring to bear vary considerably from country to country. In many cases long-term cutbacks and the declining size of the armed forces, mean that many military medical personnel are now reservists and may already be working on the "front-line" in their civilian capacity.

But troops are resourceful. They are all well-trained in basic first aid and could assist in a variety of ancillary roles. Medical units themselves might ultimately be needed to organise temporary "field" hospitals and other medical facilities.

Logistics

This is an obvious area where military skills could be deployed. Troops can help transport vital supplies - in Britain some are being trained to help maintain the supply of oxygen cylinders to hospitals.

They could also assist in the broader organisation of the logistical system. Military communications systems might equally play a part.

Security and public order

One hopes that this will not be a required military role and it would be a job that most Western governments would be eager to keep in the hands of the civilian police.

But if their available personnel significantly declines, troops could again potentially be used, though less for face-to-face contact with the public and more to protect key installations, warehouses or whatever, freeing up the police service to maintain their traditional role.

Clearly though traditions in each country differ. Many already have paramilitary police forces who in some ways mix the two roles. In the US, each state has its own National Guard - essentially a reserve military force, but one that can be deployed according to the governor's needs.

Already, governors in 27 states have activated elements of their National Guard forces for a variety of roles.

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

GETTING READY: How prepared is the UK?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Reassurance

It is a significant step for a government to call upon the military and a measure of the scale of the unfolding crisis around us. But that might help provide some reassurance that the state is fully engaged and that all resources available are being mobilised.

The military however is clearly not the answer to the pandemic. It is a small part of helping to cope with it. There is only so much troops can do. They are obviously vulnerable to the virus as well.

The Pentagon announced on Friday for example that some 2,600 US military personnel in Europe were in self-isolation over coronavirus concerns.

This pandemic has come out of the blue. The severity of the initial outbreak was covered up; warning signals were not heeded; and in many countries the response was slow. Now it's a question of mobilising all national resources just as if it was a war.

Some politicians may overdo the wartime rhetoric. But the military have to be prepared for any eventuality. General Sir Nicholas Carter, the head of Britain's armed forces, has noted that the military must be "prepared to fight the war we may have to fight, and it is now clear, that moment has arrived".

- Published5 July 2022