Stranded abroad as coronavirus closes borders

- Published

With the coronavirus spreading at a rapid pace, many governments have introduced strict controls on domestic and foreign travel.

But this has left many people trapped abroad. Some governments are working to repatriate those facing difficulty. For others though it is uncertain when they’ll see home again.

We spoke to three of them.

‘This is life and death’

Les Monkman began his holiday in Torremolinos, Spain in the early days of the outbreak.

“But things got bad very quickly,” he told the BBC.

In recent weeks, Spain has become one of worst-hit countries in the world, reporting more than 2,000 deaths. The government has extended a state of emergency and is enforcing a nation-wide lockdown to contain any further spread.

Les, a 68-year-old retiree, tried to book a flight home to the UK last week, earlier than he had planned, but his flight was eventually cancelled. He says the airline told him to contact the British embassy - the embassy told him to contact the airline.

“I have no idea what to do. I’m not saying there’s any blame here because this virus is awful. But what do I do?”

More pressing for Les is getting access to insulin. As a type-one diabetic, he will die unless he takes it daily. The supply he brought with him will last just under two weeks, but he needs more medication to assist with blood pressure and kidney disease.

“This is life and death,” he said. “I try not to think about it because I get very upset and I start trembling.”

After consulting with friends, he was able to secure a 10-day course of insulin from a pharmacist costing him nearly €90, but he is concerned about the financial blow if he has to stay in Spain for much longer.

“It feels like I’ve been dumped, like I don’t exist,” he said. “I used to be on the other side of the fence, I was a firefighter, so I helped. All my life I’ve helped. Now I’m asking for a touch and I don’t seem to be getting any.”

‘It’s getting pretty scary’

Jo Tovee quit her marketing job last year, and after visiting family in her native New Zealand, she’d planned to spend five weeks travelling around Peru. But the government there has declared a lockdown, and Jo is holed up at a hostel in Lima, banned from leaving except to buy food or medicine.

“It’s really eerie right now, the streets are empty except for armed police,” she said. “The situation is constantly evolving and there are so many rumours and misinformation going around I don’t know what is fact.”

With her travel plans scuppered, Jo has been trying to secure a flight to London – where she has been living for three years – or back to New Zealand. But no planes are allowed to enter or leave Peru except with government permission.

“The embassies, insurance companies, travel agencies and airlines have been impossible to contact and offered little to no assistance,” she said.

“Because I’m travelling on my British passport, I’ve felt the New Zealand embassy just doesn’t want to help me.”

Jo, 38, spent a week in one Lima hostel until it was raided by police and told to close all its communal areas. She has since been forced to stay in another hostel that has ramped up its prices.

“It’s getting pretty scary. I don’t trust what the Peruvian government officials are going to do next, they’re just changing things at the drop of a hat.”

In recent days, Peru has given the UK permission to repatriate around 400 stranded British nationals. The sick and elderly are being prioritised for the first flights, and Jo says it’s unclear when she’ll be on a plane.

Once back in Britain, she wants to move back home to New Zealand.

“Being [there] is the safer and more certain option for me right now as employment opportunities in the UK will be minimal,” she said. “I just want to get back home to be with my family.”

‘Now I’m not thinking about my dream, but my life’

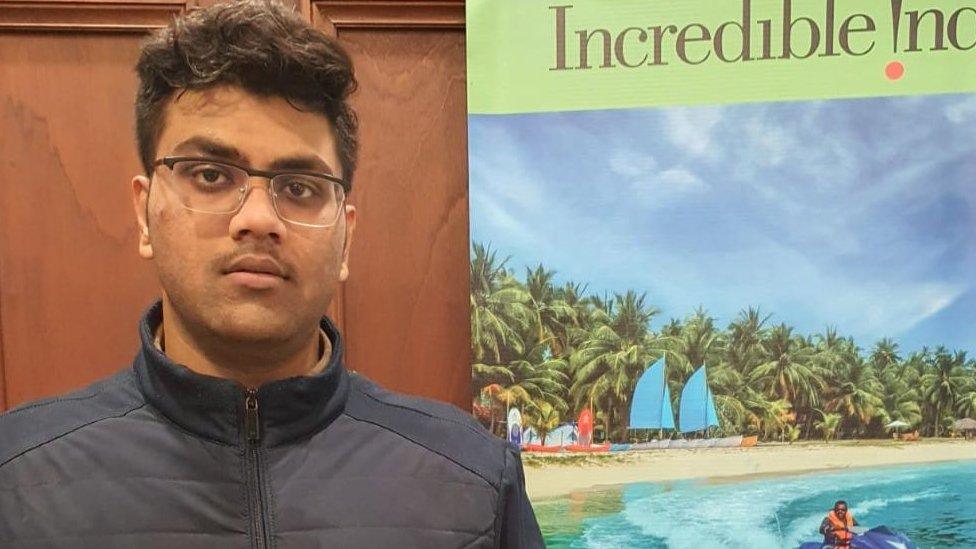

Last week, when India announced it would be banning all UK flights from 19 March, Habeeb Qureshi began to wonder when he’d see home again. Two days later, after it introduced another ban on international flights – this time from 22 March – he booked the first plane he could.

“I’m worried, anything can happen,” he said. “[Coronavirus] cases in the UK are rapidly increasing.”

Like many other Indian nationals living in Britain, Habeeb believed the second ban was an extension of the first, giving people more time to travel. He packed his bags and moved out of the London flat where he’d been living as a law student. But when he arrived at Gatwick Airport on 20 March, his airline said it was too late: the ban was already in place.

Now homeless, Habeeb slept at India’s High Commission in London last weekend. Embassy officials told him the second ban did not overrule the first, and they are waiting for more information from authorities in India.

Habeeb says he was quarantined at the embassy with over 40 other Indian nationals, most of them students and the group were only given one meal a day. On Monday, they were moved to a hotel paid for by the embassy but is unclear how long they can stay.

He is determined to return to India, no matter the effect on his studies.

“The reason we feel safer over there is because we’ll be under observation and we have less chance than the UK of being infected” he said. “We’ve got our loved ones there who care for us. We’ve got our homes, our hope.”

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash