Coronavirus: Pandemic fact v pandemic fiction?

- Published

Some scenes from the current pandemic seem right out of the darkest science fiction

Is truth stranger than fiction, as the American writer Mark Twain once suggested?

Now we all have a chance to judge for ourselves, for the veteran US journalist Lawrence Wright has just written a thriller novel, due out later this month, called The End of October.

This deals with a worldwide pandemic - a flu-like illness - that begins in the Far East but then spreads around the world. It erupts in Saudi Arabia during the annual Hajj pilgrimage. Mecca itself is sealed off with three million pilgrims.

Sound fanciful? Not when you think that China recently put some 11m people in Wuhan under lockdown and similar measures have been taken all over the world.

"The book is not prophecy," Wright wrote recently, "but its appearance in the middle of the worst pandemic in living memory is not entirely coincidental either."

The novel, he told me, started as a screenplay a decade ago, when filmmaker Ridley Scott asked him to come up with a scenario about the end of civilisation. It was never completed. But, he says, the story always haunted him, and he decided to go back to it as a novel.

Prescient

As a distinguished journalist and author of several highly successful factual books, Wright approached this just as he would any other journalistic assignment, carrying out detailed research and preparation.

As he went from expert to expert he heard clear warnings that something like the coronavirus would happen. It was a question not so much of "if" but "when", and crucially, many asked how prepared governments would be to cope with it.

"Researching the novel", he says, afforded him "the opportunity to dive in deeply enough to understand how such a crisis would play out." The book is set in 2020. "I actually created a calendar on my computer," he told me, "showing where my hero was and how the disease was progressing."

Lawrence Wright is an acclaimed journalist and novelist

Much of his research was frighteningly prescient.

"I did see it as a wake-up call," he says. "But of course, by the time the book will appear, it's more like Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year, depicting events that you can read in the newspaper every day, often, it seems to me, in concert with the events on my calendar."

Wright's use of a novel to present his argument is just part of a growing trend.

In recent years a number of other authors eager to grapple with major challenges that might threaten our way of life, have turned their backs on weighty non-fiction or semi-academic books and tried out the thriller formula themselves.

March of the robots

PW Singer, whose day-job is at the think tank, New America, is a leading expert on the way new technology is affecting our lives, especially in the military and security domains. He is fast becoming something of a veteran of the genre.

In 2015 he co-wrote with August Cole a novel called Ghost Fleet which was set in the near future and portrayed a post-communist China launching a technologically sophisticated military attack against the United States in the Pacific.

Their new book, out in May, is called Burn-In, and describes itself on the jacket as "a novel of the real robotic revolution." I have interviewed Singer several times for factual pieces on drones, high-tech rivalry and so on. So, why now turn to fiction to deal with robots and artificial intelligence?

"We feel that there is a historic revolution happening around us - literally one of the most important for human history, which will reshape the world around us," he told me. But the extent of the potential change is largely obscured from most people.

"So," he says, "we thought to blend the fiction and the fact in a new way that heightens both, and also proves useful in helping to give people a better understanding of the changes that are coming. Most people, including frankly most leaders, won't make time to read some standard academic paper. But they will read a thriller novel."

Indeed Singer argues that the changes and threats highlighted in Burn-In are made more acute by the coronavirus crisis.

"All the trends in the book," he told me, "the move to more AI; remote work; surveillance; but also social and political distrust, were already in play before the pandemic. But the indications are that they will be drastically accelerated by them."

A variety of roles that would have seen a more gradual transition and societal resistance have been pushed forward in a matter of weeks, he argues. An entire generation has been rapidly thrown into distance-learning and remote work; medicine is being conducted remotely on a scale not anticipated for a decade and AI and robotics have been deployed into roles ranging from outbreak surveillance to replacing human cleaning crews everywhere from subways to hospitals.

"After the outbreak is over," he asserts, "it is unlikely that 100% of these roles and modes will simply return back to the way they were."

Looking ahead

This kind of novel - one that seeks to extrapolate trends and warn of potential pitfalls ahead - is not new, though it may have gone out of fashion to some extent during recent more optimistic decades.

At the end of the 19th and during the early 20th Century there was an explosion of books warning of growing international rivalries and the threat of conflict to come.

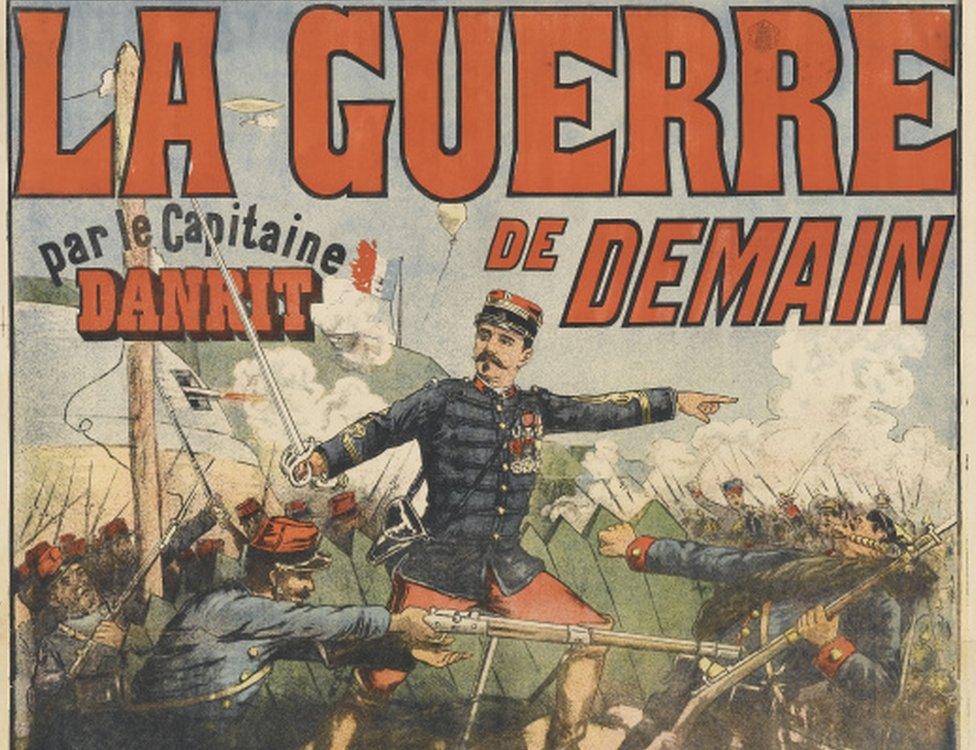

In the 1880s, a French soldier writing as Capitaine Danrit predicted future trends in warfare

Various authors, from HG Wells in Britain (The War in the Air) and Capitaine Danrit in France (La Guerre de Demain - The War of Tomorrow), wrote about futuristic combat harnessing the very latest technologies, envisaging how they might develop in years to come.

Such novels contained tanks, air power, chemical and even biological weapons. Just a few years later came the catastrophe of the Great War.

Lawrence Wright's novel has, to some extent, been overtaken by events. Nonetheless it will be fascinating to see how his fictional narrative compares to what actually ensues.

He refused to tell me how it actually ends, and even if he had I would not spoil it for you. But he tries to strike an upbeat tone in these very difficult times.

"I think this crisis is a great opportunity for a civilisational reset," he told me, "not only in the US, not only in health care, but in climate change, in politics, in social welfare, and other areas we haven't imagined yet."

And he goes back to historical precedent to make his case. "The Black Death", he notes, "marked the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance." The coronavirus pandemic, he argues "is not such an epic event, at least we hope not, but it does offer a lesson about who we are and the challenge we face to preserve and improve our civilisation."

- Published5 July 2022

- Published28 May 2021

- Published1 April 2020

- Published31 March 2020