Will the 'War on Terror' ever end?

- Published

An Afghan Special Forces member attending his graduation ceremony in Kabul last week

Last weekend's deadly knife attack in Reading, west of London, has been an uncomfortable reminder that the threat of terrorism has not gone away. But what about the so-called War on Terror, as declared by US President George W Bush in 2001? Is it still going on? And if not, has it been a triumph or a massive waste of money?

Nearly 19 years on from the day America was attacked on 11 September 2001 thousands of US servicemen and women remain stationed in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Gulf and the Horn of Africa. Drone strikes in remote regions of the world continue to target suspected terrorist leaders; counter-terrorism budgets across the world have ballooned to astronomical proportions to meet a myriad of ongoing threats.

Sasha Havliclek, the CEO of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, has been following this war since its inception. She maintains there is a distinction between the rhetoric and the reality:

"The rhetoric was done away with the minute President [Barack] Obama came into office [in 2009] but in reality there was much more continuity than rupture in the tactics of the war on terror. Under the Obama administration it's well known that they massively scaled up droning attacks, for instance, in Afghanistan and Pakistan. And for all the talk of America First now.. and I think there is a wide perception that this is winding down... we've actually seen a continued expansion of US counter-terrorism operations."

'A determined group of enemies'

That's a view largely endorsed by the man appointed by President Donald Trump as the US State Department's co-ordinator for counter-terrorism, Ambassador Nathan Sales. I asked him whether this war - as originally conceived by the Bush administration - is over?

"No, the fight is very much ongoing, we're winning the fight but we're continuing to fight against a determined enemy or I should say a determined group of enemies."

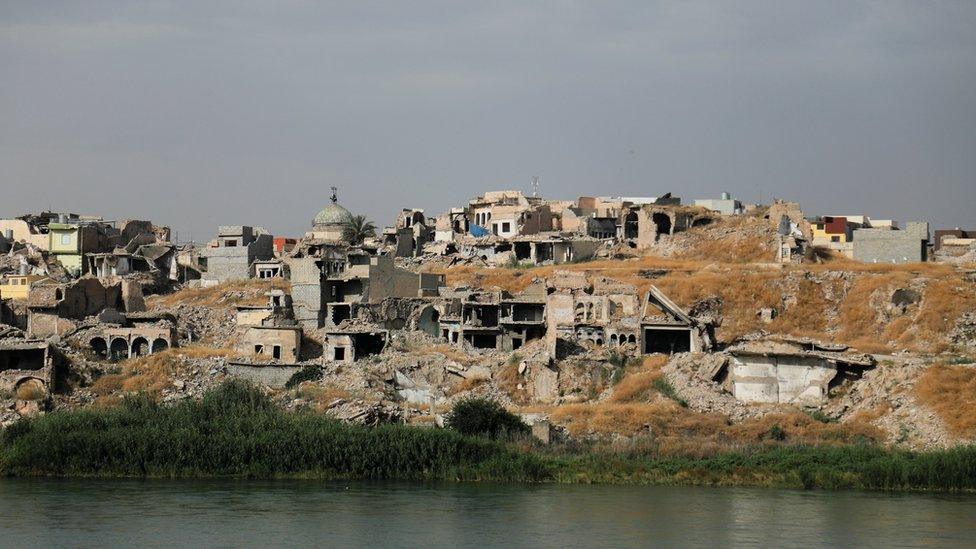

The Iraqi city of Mosul still bears the scars of the fighting

He points to the example of Islamic State (IS) where a vast, multi-national coalition successfully eliminated the last of the jihadists' physical caliphate at Baghuz in Syria last year, as well as its leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi. Yet IS affiliates and networks, he concedes, are still very active around the world.

On Wednesday, the State Department releases its annual Country Terrorism Reports.

To some in Washington, it must have all seemed so clear-cut in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the US.

Announcing the start of the "War on Terror" back then, President Bush declared that you were "either with us or against us". There was no middle ground, no allowance made for the subtle nuances of the Middle East with its ever-shifting alliances and allegiances. In Iraq, which the US and Britain invaded in 2003, this uncompromising position turned potential allies into enemies, laying the foundations for today's ongoing global jihadist movement. Mina Al-Orabi is the Editor of the UAE newspaper The National. She is originally from Mosul, Iraq's second city, which was devastated during the battle to dislodge IS from its streets.

"'In Iraq," she says, "there were clear instances where the United States undercut the Iraqi state. Of course in 2003 the decision to dismantle the police and the military, the decision to put tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of young men out of work… with the idea that they should be completely excluded from the country, that became the nucleus for al-Qaeda in Iraq and then the nucleus of IS."

'Far from over'

Other policy mistakes have also been made as a part of this war that, although later reversed by President Obama, continue to have consequences today.

The detention of hundreds of suspects without trial in Guantanamo Bay, the practice of "extraordinary rendition" - blindfolding terror suspects and flying them across the world to CIA "black sites" where they were subjected to prolonged and "enhanced interrogation".

These have all been used by critics of the West to undermine its moral authority. Ambassador Sales from the US state department says that "the world has learned a lot of lessons about what works and what doesn't and we've incorporated those lessons into our current approaches".

He is particularly irked by those critics of Guantanamo Bay, including Washington's Western partners, who have now abandoned their citizens in desolate camps strung out across Syria and Iraq. He says these countries should take them back.

It is impossible to pin down exactly how much the "War on Terror" has cost but most estimates put it well in excess of US $1 trillion. The vast bulk of that has been spent on "kinetic" military action, as well as intelligence-gathering and drone strikes. Only a tiny fraction has gone towards prevention - steering people away from the path of extremism. Shiraz Maher from Kings College London's International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation believes this war has helped spawn many of today's other problems in society.

"If you look at things like the wider Islamic State and Syria and Iraq or these types of thing," he says, "then that fuelled a degree of xenophobia in Europe, that fuelled a degree of suspicion and hostility towards Muslims, which translated into animosity towards refugees and the refugee crisis that was a result of Syria. So you can see a cascading series of consequences. So I think it's fair to say that the 'War on Terror' is far from over in many senses."

So will there ever be an end to this amorphous campaign? Will there be a decisive "Mission Accomplished" moment that brings the so-called War on Terror to a close? It is unlikely. Because, like crime, terrorism can only be reduced to what officials call "manageable levels". And today there is already a newly emerging threat, that of far-right extremism, something that will likely breathe new life into what appears to be a War without End.