Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov: Working with the Nobel Peace Prize winners

- Published

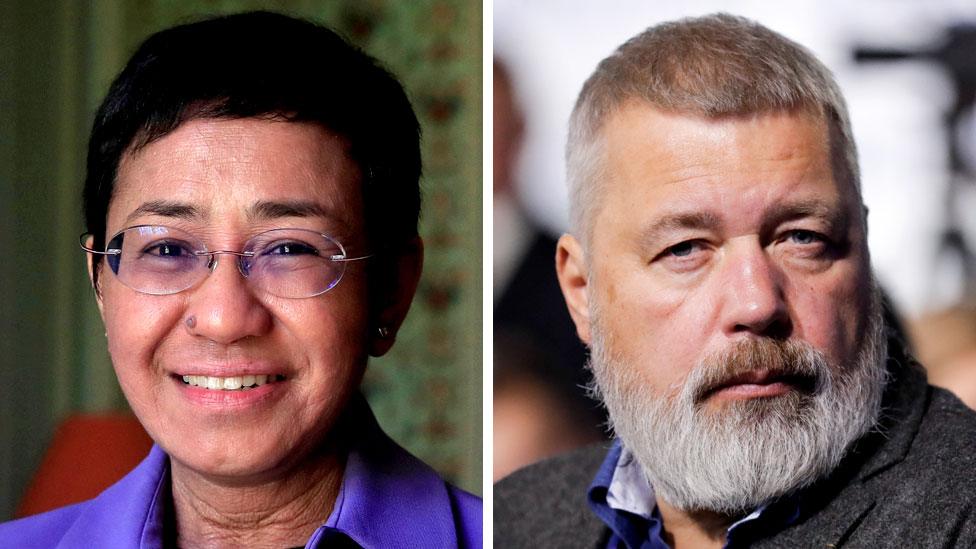

BBC journalists who have worked with Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov (pictured here, centre) share their experiences

Journalists Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their fights to defend freedom of expression in the Philippines and Russia.

Both are known for investigations that have angered their countries' rulers and both have faced threats as a result of this.

Here, BBC journalists who have worked with the pair share their experiences.

An editor who knows how to strike a balance

By Olga Prosvirova, BBC Russian

Dmitry Muratov is a complex and at times contradictory personality. Over the years of working together, I have seen him bitterly argue with his best correspondents one day, and the next rescue them from an extremely dangerous situation while they were covering a story.

Dmitry's contribution to the development of journalism in Russia cannot be underestimated. He created a unique team of journalists at an organisation that has been considered the main independent media in Russia for some time.

Novaya Gazeta participated in the Panama Papers investigation, found evidence of the presence of the Russian military in Donbas, and investigated extrajudicial executions in Chechnya.

Journalists were persecuted, kidnapped, and sometimes killed.

I have heard journalists from other media organisations ask Dmitry: "Why haven't you been shut down yet?"

To this he has replied: "It's not me you have to ask."

Dmitry Muratov is known for generating bright and radical ideas

Dmitry is an editor who knows how to strike a balance for his newspaper - between telling hard-hitting stories and not crossing the line of aggravating Russian President Vladimir Putin's administration. This balance is delicate and hard to maintain, but this skill has allowed his journalists to make a big impact over the years.

Novaya Gazeta was never a place to earn the big bucks - salaries there have been lower than in many other media outlets on the market. Yet many journalists have remained there for years, and in some cases decades.

Their dedication is due to Dmitry's ability to turn the team into a family. I recall people staying late at the office and when we would see each other the following morning we wouldn't say hello, because it felt like we hadn't parted and were sharing a home.

Dmitry was always generating bright and radical ideas. I remember we'd be in the office, each working on a story, and he would dash into the room and say: "Let's start gathering signatures against the Dima Yakovlev Law (a law that limited the rights of those in the West to adopt children in Russia)!" We would drop everything and start gathering signatures and testimonies and in the space of a day collect a box of documents to take to the presidential administration to challenge this law.

He would always help with any personal problems or issues. If anyone's family member got sick, he'd help find the best doctors or a place at a good hospital.

Anyone leaving the paper was a painful moment for him. He would treat it as a family member abandoning a home and would struggle to accept it.

How do you choose a Nobel Prize winner?

Standing by her principles against a campaign of abuse

By Jonathan Head, BBC South East Asia correspondent

Maria Ressa has been subjected to a distressing and almost certainly co-ordinated campaign of online abuse, to a pile-on of criminal lawsuits that human rights groups believe amount to state-backed harassment, and the open hostility of the Philippines' Duterte administration.

The president's followers have demonised her, as they have other journalists critical of him, as "presstitutes".

Her Nobel Peace Prize puts President Duterte and his officials in a quandary; how do they respond to this, the first Filipino to win the prestigious award?

Maria Ressa founded the Rappler news site in 2012

When Aung San Suu Kyi won the prize in 1991, a similar question might have been asked of the generals who ruled Myanmar. But they were so isolated from the world no-one really expected any response.

The Philippines, on the other hand, is a global nation, with large parts of the population living overseas. Its people do care how they are perceived, and will not easily dismiss a Nobel Peace Prize, even if they are not sympathetic to Ms Ressa.

Recall the awkward spot the government found itself in as recently as July when the country's first ever Olympic gold medal was won by weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz, who had also been attacked by Duterte's supporters.

Maria and I were both based as reporters in Jakarta in 1996 when the Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize to Jose Ramos Horta and Bishop Ximenes Belo for their campaign against human rights abuses by the Indonesian security forces in East Timor.

Bishop Belo was, in the eyes of the Jakarta government, a citizen of Indonesia, and so, like Maria, the first Nobel prize-winner in his country.

On a visit to the occupied territory shortly after the award, President Suharto chose to pretend it had never happened - he shook hands with Bishop Belo but did not mention the prize. But it had a galvanizing effect. Within less than three years Indonesia abandoned East Timor, which became an independent nation, something few thought possible in 1996.

Both of us covered the fall of the authoritarian Suharto regime in 1998, Maria for CNN, me for the BBC. The internet was in its infancy then, and the role the media played in publicising the yearning for change felt by many Indonesians could be challenged by the authorities only with the crudest methods - usually simply barring us access to places where events embarrassing to the government had taken place. Those were innocent days indeed, before the advent of organised disinformation on social media.

Maria's decision to found online news-site Rappler in 2012, when she was already a senior journalist in what was then the top Philippines television station ABS-CBN, was driven by her understanding of the way technology would transform the news business in South East Asia, where changes in the media were lagging behind those seen in Europe and the US. Rappler did not set out to confront the Duterte administration; its reporting of his election victory in 2016 was strikingly even-handed.

But it was Maria's recognition - and reporting - of the extraordinarily successful social media manipulation by the Duterte campaign that set her on a collision course with the president. Rappler's bold coverage of the brutal anti-drugs campaign then seemed to put the new media group firmly in the camp of the president's enemies.

The Nobel Committee has made some questionable decisions. But it is hard to quibble with the award to Maria Ressa, however uncomfortable it may be for President Duterte.

No journalist is perfect, and news reporting can and should be assessed critically, but Maria has stood by the essential principles of good journalism, against an intimidating campaign of abuse.

The prize she has just won just might make her life a little easier.

Related topics

- Published8 October 2021