Nuclear plant: How close was nuclear plant attack to catastrophe?

- Published

Watch: Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant appears on fire after shelling (3 March 22)

"By the grace of God, the world narrowly averted a nuclear catastrophe last night."

That was the verdict of the US ambassador to the United Nations on Friday, after Russia attacked and seized a nuclear power plant in Ukraine.

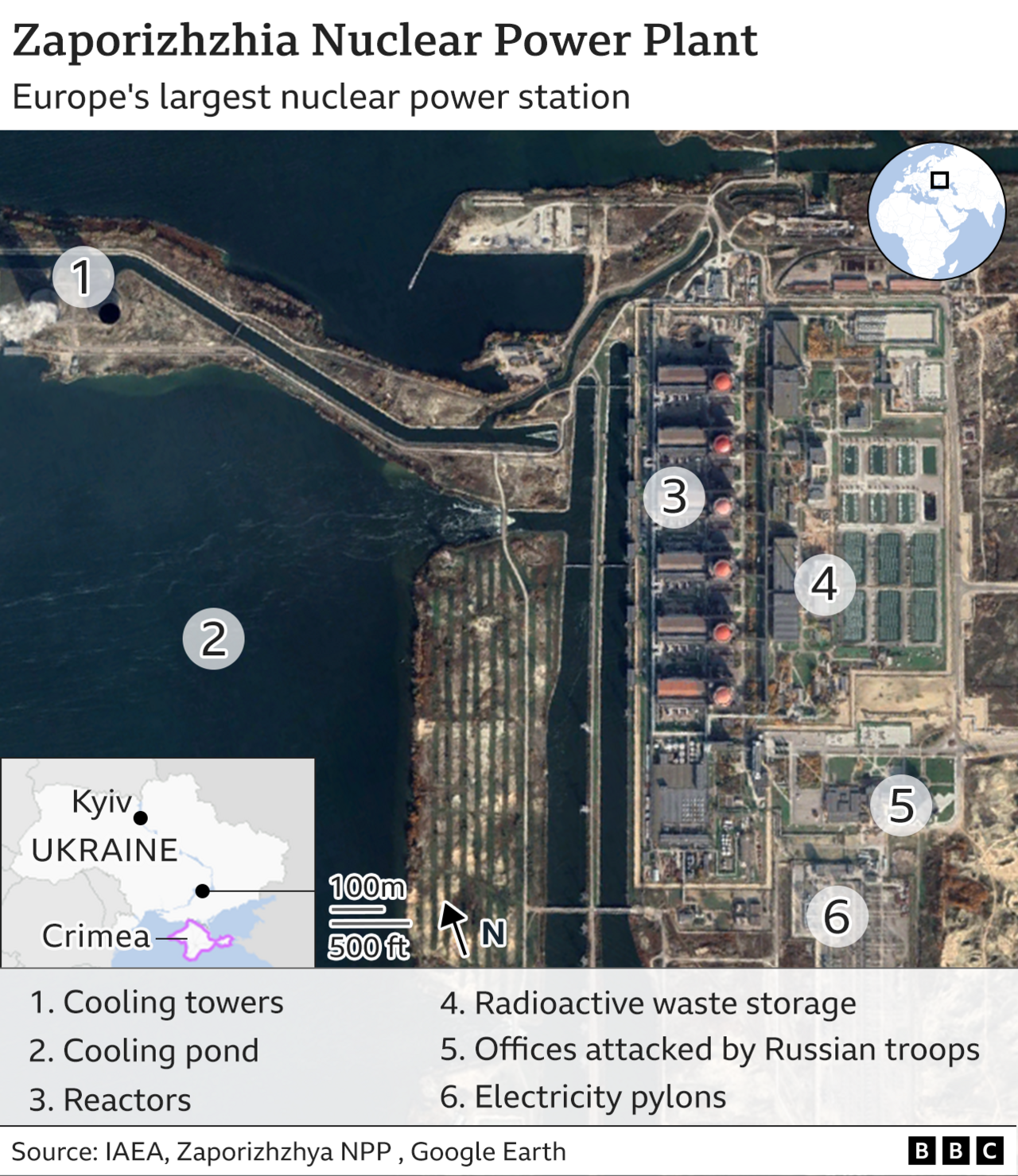

Buildings at the Zaporizhzhia plant - the largest in Europe - were damaged after it was hit by shelling.

The UN's nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), says that none of the safety systems at the plant were affected, and there was no release of radioactive material.

But it is still a very risky situation.

"For the first time this morning, I'm frightened," Sheffield University nuclear materials expert Prof Claire Corkhill told BBC News.

As well as the Zaporizhzhia plant, Russia has taken control of the now-retired Chernobyl plant - the site of the worst nuclear incident in history.

Experts have stressed that there are important differences between the two plants.

The Zaporizhzhia site is far more secure, according to Dr Mark Wenman of Imperial College London.

He says the reactor is in a steel-reinforced concrete building that can "withstand extreme external events, both natural and man-made, such as an aircraft crash or explosions".

The Zaporizhzhia plant also does not contain any graphite in its reactor.

At Chernobyl graphite caused a significant fire and was the source of the radiation plume that travelled across Europe.

Towns near Chernobyl were abandoned following the nuclear incident

However, scientists say a military attack on the reactor itself isn't the only threat. Disruption to its electricity supply could also cause serious issues.

"You don't need to hit directly a plant to get a problem," said Olexi Pasiuk, deputy director of Ecoaction, an energy pressure group in Ukraine.

The Ukrainians were in the process of taking the reactors offline to protect them. Only one of the six reactors operational at the power plant is now thought to be running.

But reactors cannot just be turned off like conventional energy supplies. They must be cooled slowly over 30 hours, which requires a constant electricity supply to the plant.

A disruption to this supply - and therefore the cooling process - could lead to radiation leaking into the surrounding environment.

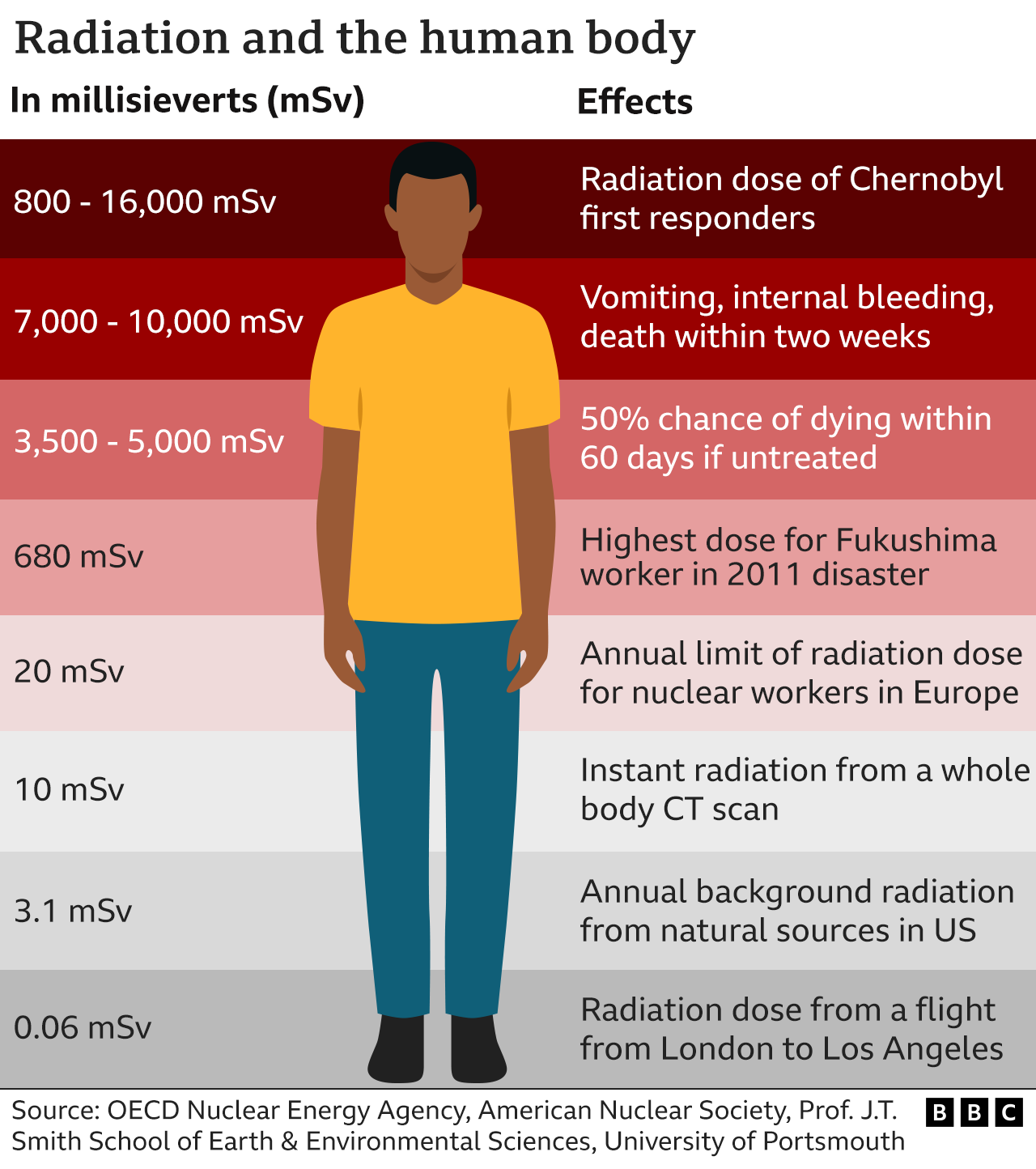

A loss of cooling like this was experienced at Japan's Fukushima plant following the 2011 tsunami.

In that case a loss of power caused a meltdown in three of its nuclear reactors.

If people are exposed to leaked radiation it can cause severe immediate and long-term health impacts, external including cancer.

This was seen in 1986 at Chernobyl.

Russia may be trying to curb Ukraine's power capabilities, Prof Corkhill said.

"They're taking the rectors offline. This means they're shutting down the nuclear reaction and putting them into a safe and stable state.

"And this could be the intention of the Russians: if you want to target their power supply, you attack a building close to the power plant and force operators to shut it down."

There are four major nuclear plants in Ukraine, and the defunct Chernobyl.

Russia has control of Zaporizhzhia and Chernobyl and it is approaching a third site - the south Ukraine nuclear power plant.

There are also smaller plants and radioactive disposal sites which store waste material from nuclear power operations across Ukraine.

On 27 February, Russian missiles also reportedly hit the site of a radioactive waste disposal facility in Kyiv.

Ukraine's nuclear inspectorate said no radiation leaks were reported, external and the plant was not directly damaged.

For now, Russian forces - who have blamed the attack on Ukrainian saboteurs - have allowed staff to remain in the control room at Zaporizhzhia, to run operations.

But world leaders have accused the Kremlin of acting recklessly. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it could "directly threaten the safety of all of Europe", and Ukraine's president accused Russia of "nuclear terror".

IAEA director general Rafael Mariano Grossi said: "We shouldn't wait for something like this to happen [again]."

He plans to travel to Ukraine to negotiate with Russian forces for the safe operation of all power plants in Ukraine.