Femicide detectives: 'Counting bodies is the best place to start'

- Published

Gulsum Kav, founder of We Will Stop Femicide

Femicide - the killing of women and girls because of their gender - is the most extreme form of gender-based violence, but in many countries no record is kept of the number of cases. BBC 100 Women spoke to three women who carry out detective work to identify femicides, and obtain justice for victims.

Gulsum Kav began a campaign to stop femicide in 2010, the year after the dead body of a teenager, Munevver Karabulut, was found in a bin in Istanbul. It took police more than six months to track down the suspect, leading to protests on the streets of Istanbul.

One of Gulsum's goals was to understand how many murders take place in Turkey, in which the killer's motive is gender-related.

Another was to provide support to Munevver's family as the case came to trial. "We have a slogan today, 'You will never walk alone,' which came from this," she says.

But soon Gulsum and her fellow activists in We Will Stop Femicide found themselves taking on the role of investigators.

Lawyer Leyla Suren and Gulsum Kav at work

"It started when a letter arrived from a family who believed their daughter had died in suspicious circumstances," she says.

This was the case of Esin Gunes, a young teacher whose body was found at the bottom of a cliff in Siirt province, south-eastern Turkey, in August 2010.

BBC 100 Women meets two women in Turkey and Ecuador who are carrying out detective work to identify femicides - the killing of women and girls because of their gender.

What is femicide?

Femicide is defined as "the murder of women because they are women, external" or "the gender-related killing of women and girls, external"

Eighteen countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have adopted specific laws making femicide a criminal offence

In many other countries the word is not widely used, but is increasingly being adopted by campaigners against gender-based violence

Esin's husband said they had gone to the area for a walk and a picnic, and she had slipped to her death. While the authorities initially accepted this story, the family didn't, as Esin had only recently returned to her husband after walking out and saying she wanted a divorce.

Gulsum's team commissioned a report which proved it was not physically possible to fall in the way she did and that she must have been thrown. This led to her husband's conviction for murder, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Since that first case, the team has worked on over 30 suspected femicides.

"We often have to gather evidence ourselves and do work like the police," says Leyla Suren, a volunteer lawyer for the group.

Another case was that of Yagmur Onut, a university student who was shot in the neck in 2016.

Her boyfriend claimed her death was an accident, but Yagmur's mother, Sevgi, believed her daughter had been murdered and contacted We Will Stop Femicide for help.

Sevgi holds a picture of her daughter, Yagmur

"They told me the struggle starts now," Sevgi says. "I started my struggle along with them."

It wasn't until January this year that the boyfriend was finally convicted of murder and sentenced to 16 years in prison.

"When you examine Yagmur's past you see that she is not a young woman who would make jokes with guns, but we had to struggle for six years to prove it," says Leyla.

The Supreme Court is now going to consider appeals. The prosecution argues the defendant should have been convicted of a graver offence (premeditated murder), while the defence argues the offence he is convicted of is already too severe.

The Turkish authorities have begun releasing data on the number of women murdered in the country, but Gulsum says the official figure is always lower than her organisation's.

She says it's impossible to separate her personal life from this struggle, but it is worth it to create a country where women are safe.

"We won't stop, we won't give up until women live with equal rights, in freedom."

Geraldina Guerra tracks cases and maps the lives of victims of femicide in Ecuador to keep their memories alive

'Counting bodies is the best place to start'

Naeemah Abrahams has been leading a team of researchers for the past 20 years to learn more about femicide in South Africa.

While activists in some countries gather information from their network of contacts, or from the media, Naeemah and her team from the South Africa Medical Research Council (SAMRC) start their work at the mortuary.

"We need to go beyond looking at cases which are already in the judicial system because otherwise this leaves out many cases where the police have already decided they are not going to prosecute, or other cases that the police haven't picked up at all," she says.

"Counting bodies is the best place to start."

At state mortuaries up and down the country, data collectors employed by the SAMRC meticulously examine pathology reports.

First they determine whether a woman was murdered, they then look for other characteristics such as the way she was killed, and evidence of a fight or rape.

"We then try to link up the file with a police investigation. But in many cases, we don't find any, and even if there is one, many times the police haven't found a perpetrator," she says.

"So we go on to do interviews with the police, collect data on the perpetrator so we can start to better identify the type of femicide it was - whether it was an intimate partner femicide or non-partner femicide."

Researchers comb through data for possible evidence of femicide

On International Women's Day Naeemah's team publishes the results of its latest femicide survey, which looks at trends of women murdered in 1999, 2009 and 2017.

"Our hope is the South African government will take over our investigative method of starting at the mortuary level," she says.

Naeemah is hopeful for swift change now that the government has asked her team to draw up a femicide prevention strategy for the country.

For Naeemah this work is about making sure femicide cases are properly counted and that the justice system works for everyone.

"We do this to change the lives of women," she says.

'We make femicide visible with maps'

A group of women researchers in Ecuador gather data on femicide, but have also found a way of remembering the lives of women who have been killed.

Ecuador is one of 18 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean that have adopted laws to criminalise femicide, according to the UN.

This means femicide rates are now being officially recorded. But, as in some other countries, women's rights groups say government figures are far too low.

"We decided to start recording cases systematically so that we could have data to then question the state institutions," says Geraldina Guerra, president of Aldea Foundation.

Geraldina Guerra

"Through our local contacts from all over the country we are able to spot cases of suspected femicides early on, sometimes long before the police or the media have found out," says Nicoletta Marinelli, another member of the team, who lives in Quito.

The group quickly starts investigating, for example by tracing the dead woman's last movements and establishing whether she had previously been a victim of domestic violence.

To begin with the Aldea Foundation made maps to compare the number of women killed in different regions, but then they took the idea a step further.

Now they build "life maps", as they call them, which place memories of the woman on a map showing the park where she went on walks, her favourite cafe, the animal shelter where she used to volunteer, or the stadium where she once saw her favourite singer perform.

"Maps then become social tools, we work with the families to populate them: we mark the spaces that these women once occupied through the voices and memories of those left behind," says Nicoletta, who co-ordinated the initiative.

The maps are available on the foundation's website, and the aim is to make the issue of femicide visible, but also relatable. "This is happening on the streets of your city, streets you are familiar with and walk every day," they say.

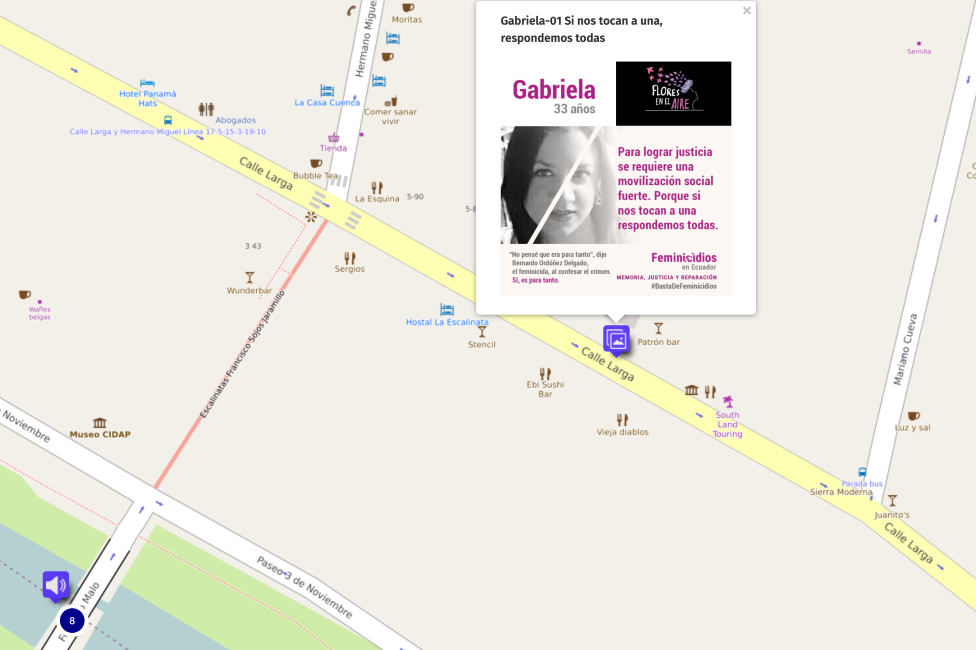

Part of the Cuenca map, remembering a woman called Gabriela

With funding from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and as part of the Spotlight Initiative to eradicate all forms of violence against women and girls, they researched and drew maps for three cities in Ecuador.

In Cuenca, a city in the southern Andes mountains, the life map commemorates Maribel Pinto, who was brutally stabbed 113 times in November 2020.

Maribel - an Afro activist and mother of five - was born in a rural area but became a sex worker to make ends meet, after moving to Cuenca. She died at the hands of a 25-year-old mechanic, who was later found guilty of femicide and jailed for 34 years.

Miriam, her daughter, helped build her map with some of the locations that bring back memories of happier days - like the ice cream parlour by the city's cathedral.

Locations such as these are marked on a victim's life map as a clickable link. Here, people are presented with audio recordings from relatives, short descriptions and photos explaining the victim's connection to the place.

Miriam contributed to the the life map for her murdered mother, Maribel

"We used to come to this place when she had a bit of money to spare, so it'll always remind me of her. Placing her here is like bringing her back to life," says the 23-year-old, who has just had a child herself.

"These maps reconstruct the lives that were truncated but also show the social dimension of the problem," adds Geraldina. "There are brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, grandmothers, mothers and fathers left behind… and we don't seem to talk about that."

The group hopes that personalising the numbers through the life maps will help start conversations on the subject of femicide.

It also thinks the maps could help lawyers and judges to better understand and frame cases of femicide.

In Geraldina's words: "Violence endures in silence and femicide will continue as long as we remain silent."

Produced and written by Lara Owen, Valeria Perasso, Georgina Pearce, Rebecca Thorn.

Watch the documentary The Femicide Detectives here, external.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world every year. Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram, external, Facebook , externaland Twitter, external. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.