What happened when Israel sent its refugees to Rwanda

- Published

Bahabelom Mengesha, who now lives in Zurich, was sent to Rwanda by Israel in 2014

As the UK presses on with its plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda, the BBC has heard evidence that, as recently as 2017, refugees despatched there by Israel were rapidly deported and are now in Europe.

Bahabelom Mengesha, a 36-year-old Eritrean man, knows what it's like to be sent to Rwanda by another country. But his stay there as an asylum seeker was brief.

He had left post-war Eritrea in 2010 and moved to Israel to claim asylum. Four years later, his permit was revoked and he was given a choice - be sent home, go to a migrant detention facility, or take $3,500 and a one-way flight to Rwanda.

It felt like no choice at all, he told the BBC, from Switzerland, where he has been living for the past seven years.

"No sane person would voluntarily go to prison," says Bahabelom of detention in Israel. "To go back to Eritrea, where imprisonment is part of the culture, this was [also] no option."

So he chose Rwanda.

But Bahabelom soon found out he wasn't welcome in the east African country. No sooner had he landed in its capital, Kigali, than he was told he must leave again for neighbouring Uganda - and all for a fee.

It is not clear who was orchestrating his expulsion from Rwanda - and that of other migrants we have spoken to - but Bahabelom believes Rwandan officials were involved.

Rwanda's status as a safe destination for refugees has been questioned, after the UK signed a deal with the country to house asylum seekers who had landed on its shores. Western nations have issued warnings about its human rights record.

The UK government had a plane ready to take asylum seekers to Rwanda earlier this month

However, there are key differences between the UK's deal with the country and Israel's.

Israel's "voluntary departure" scheme presented the flight to Rwanda as a choice, whereas the UK's scheme is compulsory. And unlike the UK, which has publicly announced its scheme, Israel never had any official agreement with Rwanda.

Nevertheless some 4,000 Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers based in Israel were sent to Rwanda and Uganda between 2013 and 2018, before the secretive arrangement, external was abandoned.

Bahabelom was flown to Kigali in September 2014.

"Being sent to Rwanda didn't stop us [reaching Europe]," he says, relating how they went from Rwanda to Uganda.

"And we didn't stop there."

The BBC has spoken to a number of former asylum seekers who were sent to Rwanda from Israel. They all took part in the scheme between 2014 and 2016 and have since settled in Europe. Separately, we are aware of at least one similar case living in the UK. Others interviewed by migration experts have given similar accounts.

Many spoke of being met at the airport in Kigali by a local man called John. This testimony spans several years so it is impossible to verify if "John" was the same person throughout. They described then having their papers taken from them by people who appeared to be Rwandan officials, before being driven to a hotel which was guarded and which they were barred from leaving.

They were then told to pay up to $500 to be driven in groups to the Ugandan border. Cars were waiting on the other side to drive them to the capital, Kampala. Again they were made to pay.

But with no work or documentation, they say they needed to keep moving - joining the well-worn migration routes across Africa and the Mediterranean to reach Europe.

Bahabelom says he didn't feel there was an option to stay in Rwanda.

"[When you are told] to pay this and to go, of course you do what you are told."

Another Eritrean asylum seeker, Mebrahtom Tesfamichael, says he challenged "John" about what was happening.

Mebrahtom Tesfamichael says he tried to discover why they were being pushed out of the country

"I had a private chat with [him]…" says Mebrahtom, who also arrived in Kigali in 2014 after spending nine months in Israel's Holot detention centre. "'You have to get out of here,' he said. I replied 'Why should we leave? When we left Israel, they told us we were getting refugee status in Rwanda and that's where we were going to live.' He only said 'Maybe you are allowed to stay for three days. After that you must be gone.'"

Tesfay Gush, an Eritrean who arrived in Rwanda in February 2015, believes the Rwandan officials and traffickers were working in tandem.

"As an African man myself I thought I would be treated fairly, and be cared for better [in Rwanda]," he says. But he realised he was not welcome when he witnessed security officials and civilians apparently working together.

"They did not want us there."

"Usually when someone assists you in crossing a border it's done covertly, but these guys did it openly. For example, when we came to checkpoints and they produced proper documents to go through unhindered. That's why I think they were officials."

Asked for comment, the Rwandan government said it was unaware of such allegations. A spokesperson said it would investigate.

"[A]nyone found to have breached our laws of ethical standards will be held to account. The Rwandan government makes the safety of its people, and anyone who comes to our country, its top priority, and that includes refugees and economic migrants."

Hot air promises

Bahabelom eventually arrived in Greece on a small boat and travelled over land to Switzerland. Now settled in Zurich, he is about to take his final exam to become a qualified plumber. He feels fortunate compared with others sent from Israel to Rwanda who also joined the migrant trail to Europe.

"I know at least 10 or more people who have lost their lives in Libya, been beheaded by Daesh [the Islamic State group], or drowned in the sea."

One expert on the Israeli scheme, Dr Yotam Gidron, says as news of the arrangement spread in migrant communities, it became a recognised means of joining the smuggling route to Europe.

"Publicly, the transfer schemes were presented as providing Sudanese and Eritreans with a stable future in Rwanda or Uganda," says Dr Gidron, of the refugee studies centre at Oxford University. "But it quickly became clear that Israel's promises of a legal status, rights, and livelihoods in these countries were merely hot air."

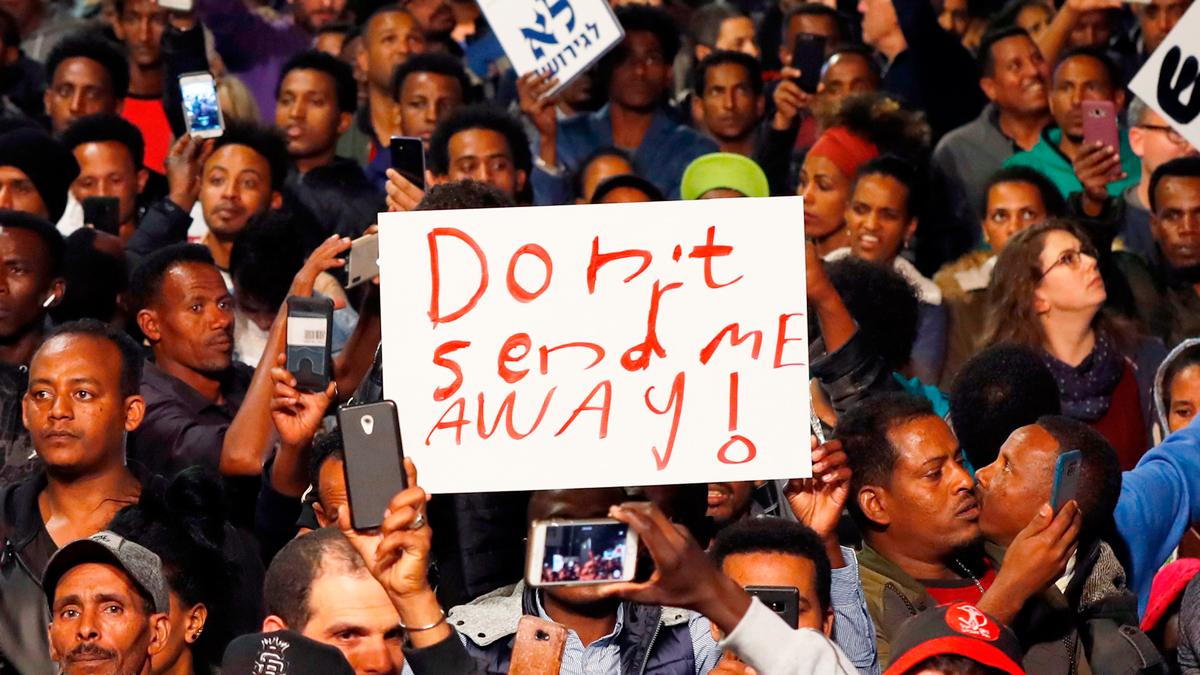

There were public protests in Israel when the government tried to formalise the deportation policy in 2018

Experts warn that deporting people to third countries can also make them more vulnerable to people trafficking.

"The risks of expelling people seeking asylum… to countries they do not know and may have no connections with are especially acute," Steve Symonds, of Amnesty International, told the BBC.

The UK government's Rwanda asylum scheme is a five-year trial which aims to send some refugees for processing and long-term settlement.

The Rwandan government said that the agreement with the UK was "wholly incomparable" to the Israeli scheme which "was abandoned when it became clear it wasn't working".

"Under the new programme, there will be a comprehensive package of support for migrants and the host community, financed by the UK government," it said.

The UK Home Office insisted its implementation will be closely overseen.

"Our world-leading and innovative Migration Partnership with Rwanda will be monitored through a bespoke joint committee, which will ensure those making dangerous journeys to the UK are relocated to Rwanda to rebuild a new life there," a spokesperson told the BBC.

- Published13 June 2024

- Published16 June 2022

- Published14 June 2022

- Published17 June 2022