A journey to the site of the Nord Stream explosions

- Published

Katya Adler travelled to the Baltic Sea, Norway's Russian border, and (pictured) a Norwegian oil field

Prosecutors in Sweden say explosions on a gas pipeline between Russia and Europe were the result of sabotage. The explosions in the Baltic Sea targeted pipelines carrying natural gas from Russia to Europe. Russia denies any involvement. Before the announcement, Katya Adler travelled to the site, and was separately told by Nato chief Jens Stoltenberg that the west could go to war if Russia attacked infrastructure providing critical energy supplies.

A Danish surveillance plane was flying round and round above our heads. To the back and the side of us, two Swedish and a Danish warship loomed. Suddenly, a Russian supply vessel appeared and anchored close by.

We hovered anxiously by our boat radio, wondering if, after all these weeks of trying to arrange exclusive access with the relevant authorities to this point in the Baltic Sea, we would be instructed by one of those warships to get out of there.

A Russian vessel and a Danish surveillance plane were spotted close to the site of the Nord Stream explosions

We were east of the Danish island Bornholm and south of the Swedish mainland, where two pipelines that stretch from Russia to Germany - Nord Stream 1 and 2 - passed beneath us.

Three explosions ripped through the pipelines in late September with the force of a huge car bomb, according to intelligence experts. But no evidence has yet come to light about who was behind the attacks.

However, on Friday a Swedish prosecutor said in a statement that traces of explosives had been found on several objects recovered from the site. The findings established the incident as "gross sabotage".

The BBC had previously been given access to the underwater site. Aside from a Swedish newspaper journalist, no other media had been allowed. We found that the extent of the blast damage was far greater than had been thought.

With us, we had Norwegian underwater drone expert Trond Larsen. He used sonar technology to examine details of the detonated pipes. Trond carefully lowered his two drones into the choppy waters, guiding them with a cleverly re-purposed gaming console.

Underwater drone footage of the damage to the Nord Stream pipeline

"Look at that, Katya," he jabbed excitedly at the laptop we had balanced in our narrow ship's cabin, which was live-streaming images captured by the drones. "Part of the pipe has shot four, five, maybe six metres straight upwards, at the point where it was blown apart.

"Now we can see how the concrete has blasted off, showing jagged edges of the steel underneath - 45 millimetres of steel flattened, ripped straight out. The speed, the force, the explosion must have been huge."

Trond's sonar imagery showed us how far, even crushingly heavy, thick concrete-coated pipe debris had been thrown across the ocean floor in the explosion.

He was intrigued to spot track marks on top of some pipe casing. A clue perhaps, he wondered, to how the explosives had been detonated, or laid? Or simply marks left by machinery when the pipes were first laid?

The backdrop to this sabotage is Russia's war in Ukraine. Sweden and Denmark are conducting their own separate investigations. Intelligence services are famously wary and secretive - even between allies.

The explosions on the pipes, which were not in use at the time, took place partly in what's known as the Swedish, and partly in the Danish, economic zones of the Baltic Sea.

The west widely thinks the Kremlin was behind the attacks, a kind of message from Moscow - part of the hybrid - or non-conventional warfare - it's waging, including cyber attacks, away from the battlefield in Ukraine.

Russia has blamed the sabotage on the west - vaguely on the US, and specifically on the UK Royal Navy, which promptly dismissed the allegation as an attempt by Russia to distract from its military failures.

Russian vessel Nefrit and Danish surveillance plane viewed through binoculars

Later, we discovered the Russian offshore vessel we had spotted was part of a separate investigation Moscow had begun into the Baltic explosions. While many in the West see this as a cynical move by Moscow, Stockholm is worried that Russia might use this as a pretext to stage a more regular presence close to Swedish shores. The country is poised to join Nato.

One thing has become clear from the explosions - the critical importance of Europe's energy infrastructure, bringing oil, gas and electricity from source to our homes and workplaces at this time of energy crisis, and the huge difficulty in protecting it.

This is now another major front line in the current conflict. At a recent energy conference in Moscow, President Vladimir Putin warned ominously that energy infrastructure "anywhere and everywhere" was under threat.

And it's not all about Nordstream.

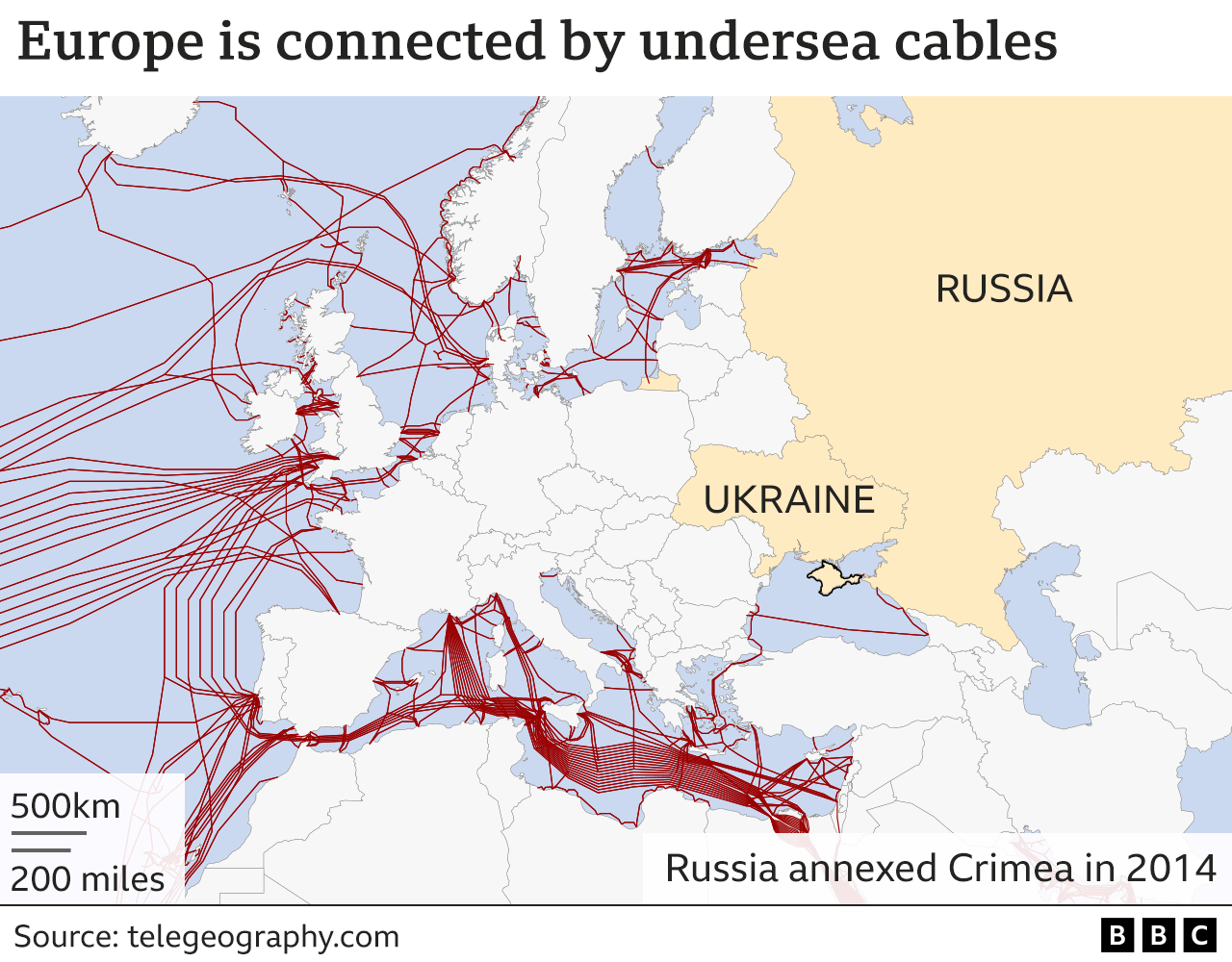

Europe has a complex web of underwater energy pipelines, many in the Baltic and the North Seas. Its waters are also home to thousands of miles of submarine electricity and internet cables, keeping us connected, and enabling trillions of dollars' worth of financial transactions a day.

The system is vulnerable, and if it shatters, it has the potential to provoke major social unrest across the continent. This is a scenario the Kremlin might welcome. It has been investing in subsea capabilities for the past two decades, and Russia has the largest fleet of spy submarines in the world.

Nato is scrambling to catch up.

In the eye of this geopolitical storm, is Nato member Norway. Now the largest natural gas supplier to the UK and EU, and amidst concerns of sabotage and espionage, Norway's military has stepped up surveillance dramatically on, above and below, the North Sea.

The BBC and a German TV crew were granted rare access to a Norwegian patrol of the many oil and gas rigs in its territorial waters.

We spent just over two days on board the Jarl, a towering naval coast guard vessel.

Massive floor-to-ceiling windows on the bridge afforded a spectacular view of the oil and gas platforms, glimmering in the rare sunshine. It was like a metallic city seascape on stilts.

The ship is equipped to be steered from four main vantage points up there. And at night, the Jarl, like other Norwegian military vessels now patrolling the area, sails in velvety darkness. Lights are turned out on the bridge. The crew likes to keep their course unpredictable, they told me, and sometimes switches off the Automatic Identification System (AIS) to be able to move around undetected.

Oil rig viewed from the Jarl

The Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Norwegian Navy, Rune Andersen, told me Norway took its responsibility as a major energy supplier seriously.

Energy security was key for Europe, he said. That is why the navy was bolstering its presence at sea, to make people feel safer and to act as a deterrent.

"Honestly I was not expecting to be doing this - patrolling energy installations for security," 20-year-old Alexander told me. He is one of the many military conscripts I met on board the Jarl.

Military conscript Alexander on the bridge of the Jarl

"The situation is a bit tense," continued Alexander. "Some people in my family aren't very comfortable about me doing this job. But there's no threat to me. I feel safe. I feel our job is more important now."

Norway's navy keeps in regular contact with the private companies running the oil and gas rigs.

Along with two officers, I got dressed into a snug orange and black thermal suit, gloves and helmet, before being lowered off the side of the Jarl inside a jet-propelled dinghy, and finally dropped, with a mighty splash, into the North Sea.

Onboard a jet propelled dinghy

Before the pipeline attack, Norway's navy and coast guard used these speed boats for search and rescue missions and fishery inspections. Now, they are being called on to investigate the increasing number of drone sightings called in by the oil and gas companies out here.

Norway's prime minister, Jonas Gahr Støre describes this as the tensest security situation the country has faced in decades. The oil and gas companies are definitely jumpy.

One of the naval officers confided that some of the "drone" sightings turn out to be seagulls. But certainly not all of them.

Norwegian-Russian border

In Norway itself, Russian citizens have been banned from flying drones after a number of Russians suspected of gathering intelligence on energy infrastructure were arrested in separate incidents. These included the son of a close friend of Vladmir Putin, and a Brazilian academic now believed to have been an undercover Russian agent.

The first of this latest round of arrests was in early October in Norway's wild and beautiful north, where the country comes face-to-face with Russia.

A 50-year-old man was apprehended at the Storskog crossing point - now the only land border to Europe open for Russian tourists - as he was leaving the country. He was reportedly in possession of two Russian and one Israeli passports, two drones and a series of partially encrypted photos and videos.

Moscow dismissed that arrest, and the other spying allegations against Russians in Norway, as "hysteria".

We travelled to the crossing point, on the nearly 200km-long Arctic border, to see if Norway's heightened anxiety over its neighbour is affecting the local community there.

Solve Solheim, the head of border surveillance for the area, told us the case had taken them by surprise. The encrypted photos and videos, never mind drones and multiple passports, was all highly unusual - he said.

He insists his country isn't overreacting. Norwegians had been perhaps a bit naive in the past regarding Russia, he told us. Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine, had served as a reality check.

Local police have told residents to be more watchful, and to report drone sightings, or vehicles and individuals, that might appear suspicious.

Living and working so close to Russia, and far away from the Norwegian capital Oslo, Solve Solheim says he's often felt on the front line. Now, he said, it seemed like a new Cold War had returned to Europe.

Corner shop owner, Alf Hammer told us that he had never seen a Russian until the end of the Cold War. Now, they were part of the community up here, he said - married to Norwegians, with families. His wife, Natalja, was originally from St Petersburg.

Alf and Natalja Hammer

They smilingly wrapped their arms around one another to squeeze close enough to speak simultaneously into our BBC radio mic.

They were dismissive about what they saw as Russia-paranoia in southern Norway, especially in Oslo.

There, people were more suspicious of Russians - Alf told us - because they weren't exposed to them.

"Some idiot flies a drone and they make a big fuss about it," he said.

"They don't all support the invasion of Ukraine, you know," Natalja said pointedly. "It's just at home in Russia, they can't say that."

But Norway's defence minister, Bjørn Arild Gram, told me Norway had no choice but to remain vigilant.

I met him while he was paying a visit to Norwegian Home Guard troops on watch at a key oil refinery - near the country's second city, Bergen.

"We just don't know what might happen. We hear the sharpening rhetoric [from Moscow]. Energy is being weaponised in this conflict. We in Norway are now the biggest exporters of natural gas - so the infrastructure here is of huge strategic importance."

Norway has earned vast sums of money from energy exports during the current crisis. But it is now beginning to feel the political heat.

Millions of families across Europe are fretting about the coming winter. And governments in Germany and the UK want to know they really can rely on Norway's energy supply.

The two countries, plus France, are providing naval support to Norway around its energy infrastructure.

But Europe, once again, stands accused of having sleepwalked into an unnecessarily exposed position.

Back in 2017, Rishi Sunak, now UK prime minister, was a not-very-prominent backbench MP. He wrote a paper warning that a large-scale attack on UK undersea infrastructure would be an "existential threat to national security". And he called for steps to be taken to mitigate risks and ensure "our maritime assets are sufficient to the task".

Yet his defence secretary, Ben Wallace, recently announced that the UK's first multi-role ocean surveillance ship would only be operational sometime next year.

France, meanwhile, only produced its seabed war strategy back in February - after Russia invaded Ukraine.

In Brussels, at Nato HQ, I spoke to the head of the alliance - Norwegian, Jens Stoltenberg. He insisted Nato had been debating subsea safety for a long time.

Could an attack on critical underwater infrastructure be considered an act of war, I asked.

Yes, said Jens Stoltenberg. It could trigger Nato's collective defence clause - where an attack on one ally is considered an attack against all.

Strong words Nato would rather not put into practice. Its aim remains to avoid direct military conflict with Russia - for obvious, potentially nuclear, reasons.

But as it flounders militarily in Ukraine, the Kremlin is waging determined, non-conventional warfare closer to our homes.

By threatening our gas supplies, Vladimir Putin aims to advance on two other fronts. Hoping to weaken and destabilise Europe's governments and, as a consequence, reduce western support for Kyiv.