Women's World Cup: Players put 'at risk' at qualifiers

- Published

Thirty-two teams will compete in this year's Women's World Cup

The world's top women footballers are being put at risk because of a lack of pay, medical supervision and suitable training facilities, according to a new report.

The players' union Fifpro says conditions are a "barrier to performance" at the world's six continental championships.

All, except Europe's, are used as qualifying rounds for the World Cup.

The BBC has asked world football's governing body Fifa for comment.

Fifpro are warning that inadequate playing and support conditions are having a big impact on the health and wellbeing of international football players. A previous Fifpro study suggested that more than one in three footballers experience depressive symptoms.

Earlier this year, Fifa announced equal conditions - but not equal prize money - for its women's and men's World Cup tournaments, including better travel provisions and private hotel rooms for each player.

Now Fifpro are calling for equal conditions when it comes to the pathways to the World Cup as well.

"The obligations and pressures have increased with the upward trajectory of professionalisation but the conditions and wellbeing of players has either stayed the same or actually decreased," Dr Alex Culvin, Fifpro's head of research for women's football told the BBC's 100 Women.

For her, its crucial that the right care is offered to the more than half of players who reported either not receiving, or not being aware of, mental health support.

Medical care

Fifpro says almost one in three players surveyed said they are not paid by their national team for these matches. More than half said they didn't get a pre-tournament medical examination.

"It is not an environment that supports players to be at their best all of the time," says Sarah Gregorius, Fifpro's director of strategic relations for women's football.

When it comes to pre-tournament medicals, she says, "the numbers on their own are quite shocking and dangerous".

She wants to see all players offered one and anything less is "completely unacceptable".

Many countries have a long history of men's professional football and experts say this established infrastructure is partly why medical care for male players is more consistent compared to women's football.

"Because of the limited number of [women's] professional clubs who offer professional standards... the need for women players to have these tests done at the international level is greater," says Dr Culvin.

She points to the Confederation of African Football (Caf) as an example of what can be achieved - its players reported a much higher likelihood of receiving adequate health checks compared to players at other confederation championships.

"Caf had made a real effort to give a medical and an ECG [electrocardiogram - to check heart rhythms] to all of the players... so when confederations make it a priority, the data can shift," she says.

Nearly all of those who took part in the Fifpro research said that pay and prize money needed to be improved.

Almost one third of those surveyed said they had to take unpaid leave from other employment to take part in qualifying rounds.

"Players have to make a choice between competing for their national team in international tournaments or maintaining their second job and another source of income. A choice players should not have to make," says Fifpro in its report.

'World Cup dream'

As part of Fifa's recent commitment to minimum conditions for this year's Women's World Cup tournament - taking place in Australia and New Zealand - it promised a share of prize money for players.

Each individual player from the squad of up to 23 players will be given an amount of money depending on their team's achievement in the competition, from $30,000 (£23,476) for those exiting at the group stage, up to $270,000 (£211,286) for each player in the winning team.

Qualifying for the Women's World Cup has made Zambia pay attention to women's football, says Evarine Katongo

This year will be the first time a team from Zambia - men's or women's - will appear in a football World Cup competition. It has made everyone in the country pay attention to women's football, says Evarine Katongo, a midfielder on the qualifying team.

She thinks Fifa's promise is a step in the right direction for footballers who come from challenging backgrounds or low incomes.

"It really will make an impact, especially to the African players," she says. "It will really help them to do good for their family and probably it will help them make ends meet."

Although she sees women's football becoming more popular in Zambia, when it comes to pursuing her own dreams, Evarine says success lies abroad, where there is more money and opportunity.

"My dream for myself at the World Cup is to be scouted by another team," she says.

"I don't see myself playing for the local league in Zambia again after the World Cup."

Fifpro survey in detail

A total of 362 players, across six confederations, completed the survey.

Five out of six confederations used continental championships to decide which countries would qualify - only Uefa held a separate competition.

"During qualification the conditions that the players are exposed to and expected to deliver in, during some of the biggest competitive moments of their lives, are not up to the standards of elite international football, putting both the players and the sport at risk," Fifpro leaders said in the report's opening statement.

'Many sacrifices'

One player who has achieved success with a bigger club is Colombian international Leicy Santos, who moved to Spain to play professionally for Atletico Madrid in 2019.

Earlier in her career, she faced immense financial hardship in order to pursue her dream.

"I come from a very humble family," she says of her time growing up in rural Colombia.

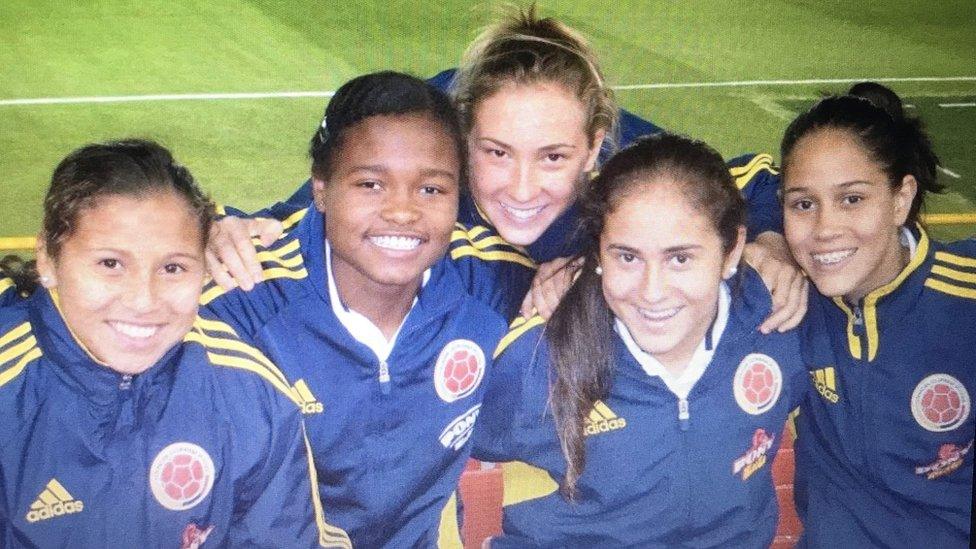

Leicy Santos will be playing in her second World Cup this year, after first appearing for Colombia in 2015

"Until I joined the Colombian national team in 2012, I didn't have any financial support. Then I started to earn a small amount of money every time I went to training, they [the national team] paid my travel expenses," she says.

"At that point I stopped asking my parents for money and rather helped them as much as I could, but what they [the national team] paid me wasn't much either."

Despite being part of the national team, it still wasn't possible for her to make a living only from football, and Leicy says she cleaned houses with her mother to help contribute towards the family's income.

"The reality is that you don't have a constant support that allows you to make a living from football and focus only on the sport," she says.

Leicy (far left) joined Colombia's youth team in 2012

In 2019, Atletico Madrid signed Leicy and that's when she noticed a huge change in her professional experience.

"I am in a club that offers me everything - training facilities, medical services, a salary," she says.

"I know that I am privileged; there are clubs that even in my same league here in Spain do not provide any of this and [the players] have a very bad time."

Organisers are hoping a record two billion people will watch the Women's World Cup this year, nearly double the 1.12 billion viewers for the 2019 tournament in France.

"I just think it's an incredible way to smash the stereotypes that have persisted," says Jennifer Cooper, UN Women's sport lead.

"It shows that women are capable. It provides role models and dreams for girls and... it normalises that men and women both play football."

The BBC contacted Fifa, the six confederations and the national teams for Colombia and Zambia to make a statement but none were provided.

Additional reporting by Agustina Latourrette and Celestine Karoney.