Gloria Steinem: Feminist icon on 'lethal' desire to control wombs

- Published

Gloria Steinem: The desire to control the womb is often lethal

At 89 years old, feminist icon, writer and magazine editor, Gloria Steinem has no plans to retire from a long career of challenging the status quo.

It's over 50 years since the political activist masterminded the Women's Action Alliance.

It was a group dedicated to fighting sexism, and Steinem - one of three co-founders - became the face of the women's liberation movement in the United States for the rest of the 20th Century.

She started her career as a journalist in New York in the 1970s and went on to co-found Ms. magazine, one of the first publications to focus on other women's issues than the perils of housekeeping and the mandates of the beauty industry.

In her apartment on Manhattan's Upper East Side there's evidence of a life lived on the road, with artefacts from places she's visited adorning every surface.

But these days she is mostly settled in New York, "happy to be in my neighbourhood," she says.

"I'm still, now, hyper-conscious of how great it is to be here."

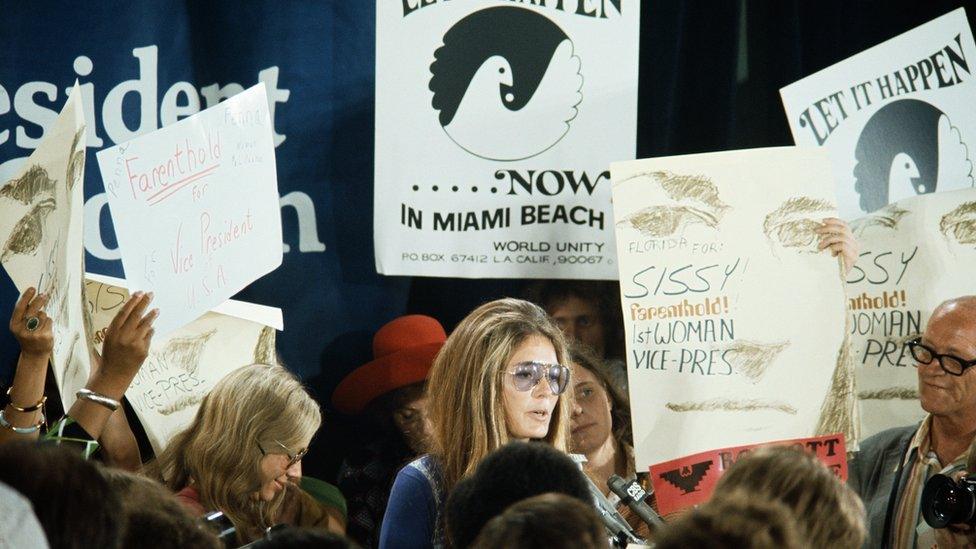

It's over 50 years since Steinem became a political figure - and she hasn't stopped working

The apartment serves as the headquarters of her foundation, Gloria's Foundation, and as a place for women, journalists, activists and community leaders to gather now that she is at home more often.

Gloria Steinem has been named one of the BBC's 100 Women for 2023.

BBC 100 Women names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world every year - Gloria Steinem is on this year's list

A 'basic' right

During the 1970s, Gloria Steinem was one of the main voices campaigning for women's reproductive rights.

She celebrated the US Supreme Court's 1973 ruling in the case of Roe v Wade, which granted women the constitutional right to abortion.

Nearly half a century later she witnessed the reversal of this decision - the Supreme Court's historic ruling in June last year that ended the nationwide right to abortion.

Anti-abortion groups across the US welcome the reversal of Roe v Wade in 2022

For Steinem and other pro-choice activists it was a stark reminder of the need to keep campaigning, to achieve changes she says she hopes to see in her lifetime.

"The most obvious and simplest [change] is that we can determine the fate of our own physical selves, so we can decide whether and when to have children, not to have children… whatever it is about our physical selves.

"That's where our difficulty begins, because we happen to have wombs and there is a desire to control wombs that is very central to authoritarian systems. Clearly, because we have a womb and men don't, the desire to control the womb is often the most lethal kind of effort."

As women's access to reproductive rights has become more limited in the US, some women in Latin America have successfully campaigned for the right to legal abortion and Steinem, who has been at the front line of countless street demonstrations in her life, admires their determined activism.

"Using our voices, protesting with our bodies, supporting other women is what the revolution is all about," she says.

"Reproductive freedom is basic, maybe more basic than freedom of speech."

Many forms of revolution

Steinem: It is not women's responsibility to make a revolution for men, as they adapt to new gender roles

With five decades of advocacy behind her, Steinem is in a unique position to reflect on the progress women have made.

In the US one major step forward has been an increase in the proportion of women turning out to vote, she points out.

Other benchmarks are directly related to the family and the daily life of women, she says.

"Some are very domestic. Who is raising the children? Who is making dinner? Who is doing the dishes? That's crucial.

"There has been progress, just not enough," she says.

Steinem closely monitors the pressure on women's rights across the world, including the curtailment of freedoms in countries like Iran and Afghanistan.

She regards the protests by Iranian women - who took to the streets burning their hijabs and chanting "Woman, Life, Freedom", after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in the custody of Iran's morality police - as both a battle for self-determination and a form of feminist revolution.

Women cut off their hair in protest at the death of Amini, who was arrested for allegedly breaking hijab rules

"They are fighting for the idea that a woman's body is not shameful or to be restricted, just as men's bodies are not, so whether they use the word 'feminism' or not, is up to them," Steinem says.

"Some people say 'women power', or 'women's liberation'. It's up to us."

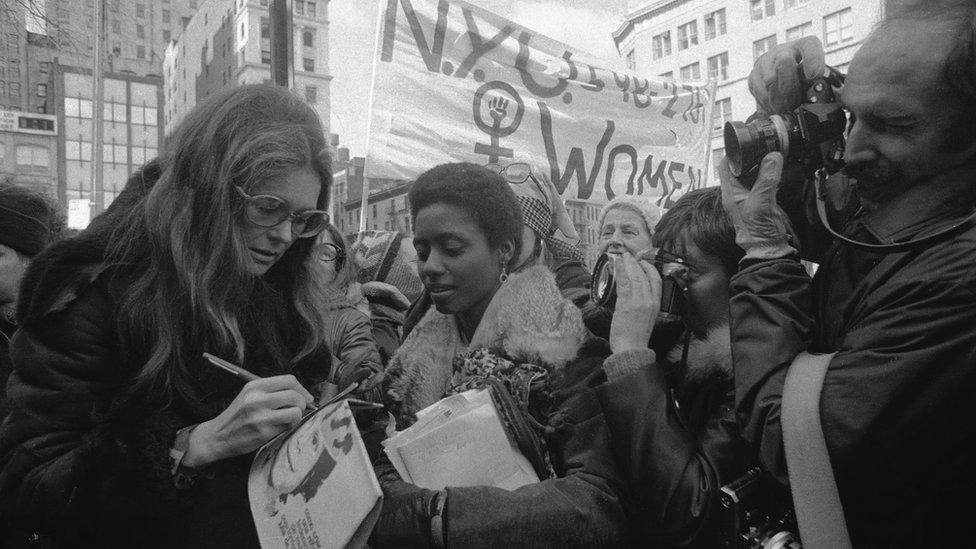

The intersection of gender and race has always been the focus of Gloria Steinem's work.

In the 1970s she worked closely with black political activist Angela Davis.

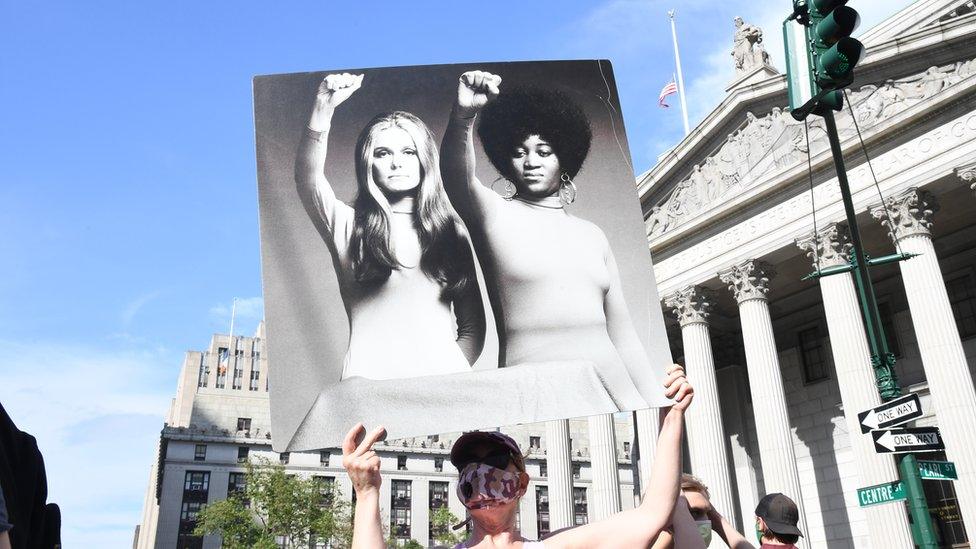

A photo of Steinem and fellow feminist Dorothy Pitman Hughes standing shoulder to shoulder with their fists in the air became an iconic image of the fight by women and African Americans for equality and social justice.

Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes posed for what became an iconic photo of the feminist movement

Yet many around the world have criticised Western feminism for not being inclusive enough.

"That's probably true," says Steinem.

"I mean, we're dealing with racism in this country. We have always generally tried to say, 'OK, if the group we're starting with doesn't look like the country, then we should wait until it does.' You know, to do our best to represent all the women who are affected by a particular issue."

'No to cancel culture'

Steinem remembers the days in which hand-outs and calls to action were made on a primitive duplicating machine called a mimeograph. She has now embraced the opportunities to connect remotely, fostered by the pandemic, and to reach a wider audience using the internet and social media.

"The problem with the internet is that it's discriminatory, because not everyone can afford to have a computer or understands the technology or knows how to express themselves on the web. And that's worrisome," she says.

Even more so, she adds, "since probably men have more access to technology than women do".

Steinem believes in the power of public demonstrations - here, with actress Jane Fonda (centre) in Washington

Steinem also expresses concern about cancel culture, and the impact on younger generations and social media users.

She tells BBC 100 Women she hasn't experienced it herself but resents it on behalf of anybody who has, "because free speech is crucial to any democracy".

"We should not submit to cancel culture, it's social pressure as censorship, and it's definitely not a good thing even when it is suppressing evidence of bias. It still is silencing people."

Change in the home

Some might argue that one of the shortcomings of feminism has been its inability to help men navigate change as gender roles are redefined. For Gloria Steinem though, it is not women's responsibility to "make [men] their revolution and their dinner".

That some men reject feminism should be expected, she says, as it is not beneficial for those "using masculinity to dominate".

She believes change has to start from within our own homes.

"That's where a lack of democracy begins, and that's the beginning of the change that we all can make," she says.

It's been over 50 years since the political activist masterminded the Women's Action Alliance.

Days are busy at the Steinem house and foundation. There are books she needs to sign and meetings she needs to attend.

As she sits at a table in the corner of her living room signing posters for an event, the doors of her apartment swing open and two women walk in.

"It is just great to be home more," Steinem repeats.

She gets up to join them on the other side of the room.

"I turned my living room into a place for talking circles. You know, revolution is like a liquid that's being poured into different containers. It changes its form, but it's still the same liquid."

Video filmed by Andrew Blum. Edited by Rachel Qureshi and Munira Mohamed.

BBC 100 WOMEN IN CONVERSATION: Gloria Steinem, external

'Bodily autonomy should be women's rights priority'

BBC 100 Women names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world every year. Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram , externaland Facebook, external. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.

- Published27 November 2023

- Published21 November 2023