Putin wants Berlin assassin Vadim Krasikov, but prisoner swap is murky

- Published

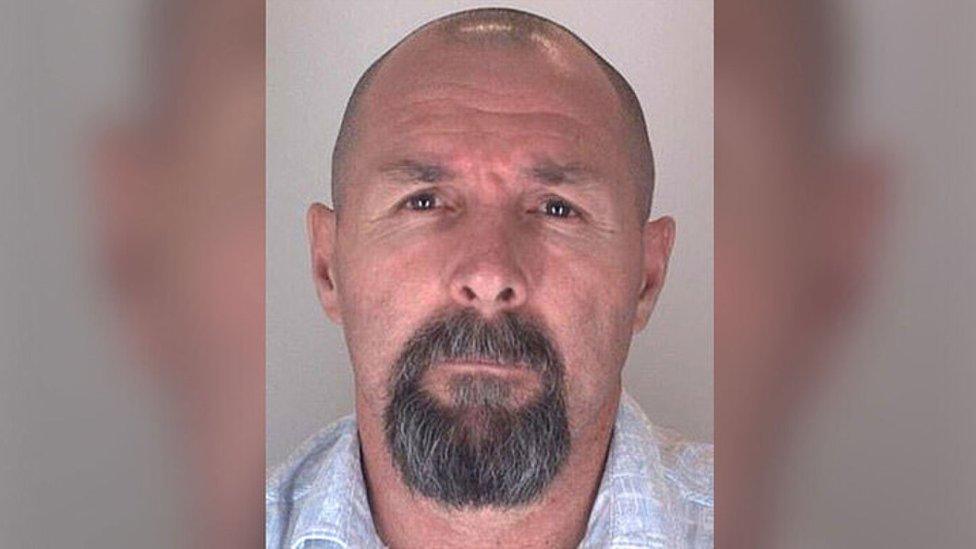

A court found Vadim Krasikov was acting under Kremlin orders when he executed a Chechen separatist in Berlin in 2019.

It is now one year since American journalist Evan Gershkovich was detained on a reporting trip in Russia. His best hope of release may be Vadim Krasikov, who is sitting in a German jail, convicted of an execution that was ordered by the Kremlin.

In the summer of 2013, a Moscow restaurant owner was gunned down in the Russian capital. A hooded man jumped off a bike and shot his victim twice before fleeing.

Six years later, an exiled Chechen commander, Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, was murdered in a busy Berlin park in eerily similar circumstances, shot by a man on a bike with a silenced Glock 26 in broad daylight.

The assailant was arrested after dumping a pistol and wig in the River Spree close to the Reichstag, the building housing the German parliament.

A passport bearing the name "Vadim Sokolov" was found on the Berlin assassin, but authorities quickly concluded that was not his name after all.

The bald, strongly built man they had arrested was actually Vadim Krasikov, a Russian national with links to the FSB, the Russian security service - and the prime suspect in the 2013 murder in Moscow.

In a recent interview with US TV talk show host Tucker Carlson, Russia's President Vladimir Putin appeared to confirm reports that his country was seeking the release of the "patriot" Krasikov in exchange for American journalist Evan Gershkovich.

This month marked one year since Mr Gershkovich, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, was detained in Russia on espionage charges that are denied by him, his newspaper and the US government.

Mr Gershkovich isn't the only American in a Russian jail whose fate could be entwined with Krasikov's. Former US Marine Paul Whelan and US-Russian citizen Alsu Kurmasheva are also detained in Russia on charges widely viewed as politically motivated.

Paul Whelan (L) has been in detention since 2018, Alsu Kurmasheva (C) since October last year and Evan Gershkovich since last March

Even the late Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny, who was serving a 19-year prison sentence in Russia, was said to be part of a swap involving Krasikov before he died, according to his allies. Following the Russian election, President Putin said he had agreed to release Navalny in return "for some people" held in the West, but the White House said that was the first it had heard of any such deal.

If President Putin's price stays the same, it means the most viable way of securing the release of the detained Americans would be a complex prisoner swap for Krasikov needing the cooperation of Germany, the US and Russia.

Speaking to the BBC, German politician Roderich Kiesewetter said the deal would force Berlin into "hostage diplomacy". So why does Putin seem so desperate to get Krasikov back?

State-sanctioned killing

The first clues of a possible Kremlin hand in the Berlin murder come from Krasikov's background - or rather, the lack of one.

Documents obtained by the Bellingcat investigative website show he was wanted over the 2013 Moscow murder. However, two years later, the arrest warrant was withdrawn and the "Vadim Krasikov" identity seemingly vanished into thin air.

That is when "Vadim Sokolov", age 45, appeared. In 2015 he got a passport, and, in 2019, a tax identification number.

A German court concluded that this documentation could only be sanctioned by the Kremlin, and therefore that Vadim Krasikov had state support for the Berlin murder.

"Russian state authorities ordered the accused to liquidate the victim," a German presiding judge said after sentencing Krasikov to life in prison.

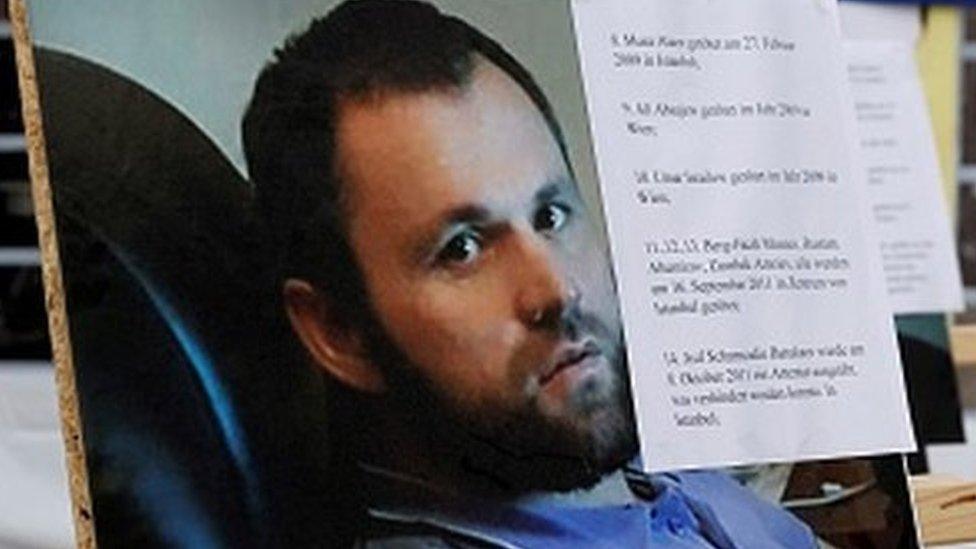

Germany expelled two Russian diplomats in response to the murder of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili

His victim, Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, was a Chechen rebel commander between 2000 and 2004, when Chechnya was fighting a war of independence against Russia.

To Western observers, Mr Khangoshvili seemed likely to be part of a string of Moscow-ordered assassinations of Chechen exiles in Europe and the Middle East.

The Kremlin denied orchestrating the Berlin murder, and dismissed the verdict against Krasikov as "politically motivated".

However, in his Tucker Carlson interview, President Putin appeared to make an admission when he said negotiations were under way for an exchange involving a Russian "patriot" who had "eliminated a bandit" in a European capital.

Ulrich Lechte, who sits on the German government's foreign affairs committee, told the BBC that President Putin's desire to retrieve Krasikov is "a clear admission of guilt and shows how unscrupulously and unchallenged Russia has been able to act in our country".

FSB's contract with assassins

Vadim Krasikov belonged to the highly secretive 'Vympel' unit of Russia's secret service, the FSB, according to prosecutors at his trial.

"Its official remit is counter-terrorism operations at home, but it has in many ways returned to its original roots, as a unit tasked with covert 'wet-work' - sabotage and assassination - abroad," Putin historian and Russian security expert Mark Galeotti told the BBC.

Krasikov personally met Putin at a target shooting range while serving with Vympel, owned a BMW and Porsche, and travelled for work regularly, according to an interview, external his brother-in-law gave The Insider.

An association between Krasikov and the FSB would provide one explanation for why Vladimir Putin, a former foreign intelligence officer himself, would be willing to hand over a prisoner of the value of Evan Gershkovich.

But Mark Galeotti said a potential deal says more about Russia's social contract with agents abroad than the value of Krasikov individually.

"It [Russia] says 'look, if you do get caught, we will get you back, one way or the other. It may take a long time, but we will get you back'," Mr Galeotti said. "That's very important for getting people to put themselves in potentially very dangerous situations."

But whether Krasikov will ever be allowed back to Russia is ultimately up to the German government.

The BBC approached three members of the government's foreign affairs committee, all of whom oppose releasing Krasikov.

Ulrich Lechte, whose Free Democratic Party is part of Chancellor Olaf Scholz's government, insisted that Germany "must not do Russia this favour".

"This is a kind of amnesty and sends the political signal that Russia can commit further murders on our territory, which will then be released and thus remain unpunished," Mr Lechte told the BBC.

Politicians on Germany's foreign affairs committee say Zelimkhan Khangoshvili's murder was "state terrorism"

"It must not be allowed to prevail that foreign citizens are arbitrarily arrested in order to abuse them for a prisoner exchange."

Jürgen Hardt, from the Christian Democrats, said he "didn't see any political support" for rumoured prisoner swaps involving Krasikov.

Even if there was political will in Berlin to release Krasikov, the legal mechanics which could make that happen are murky.

He could be pardoned by the president, or deported to serve the remainder of his sentence in Russia - something that almost certainly wouldn't happen in light of Putin's comments.

One case in point is the Russian "Merchant of Death", Viktor Bout, an infamous arms dealer released from US custody as part of a prisoner exchange with US basketball star Brittney Griner. Bout has now pivoted to politics and won a seat at a local election in Russia.

A protest against the Putin regime was held in Berlin during the Russian election.

Nicola Bier, a German lawyer focusing on extradition law, told the BBC there is "no legal mechanism that is really designed for this particular situation", so any move would be highly controversial and political.

Anti-Kremlin political activist Bill Browder is now compiling a list of more than 50 Russian prisoners in Western countries who could be used as bargaining chips to free activists and journalists detained in Russia.

Browder hopes the effort could help release British-Russian journalist Vladimir Kara-Murza, sentenced to 25 years in jail for treason for speaking out against the war in Ukraine, as well as Evan Gershkovich.

Asked by the BBC whether his campaign played into "hostage diplomacy", Browder conceded it is "far from ideal", but necessary to save lives.

After Alexei Navalny's death, Browder said, "it's clear that other hostages are at risk of dying".

Related topics

- Published26 February 2024

- Published15 December 2021

- Published20 December 2023