Nelson Mandela death: The man who destroyed apartheid

- Published

What was apartheid? A 90-second look back at decades of injustice

After being jailed for life in 1964, Nelson Mandela became a worldwide symbol of resistance to apartheid. But his opposition to racism began many years before.

Born in the rural Transkei on 18 July 1918 into an African royal family largely dispossessed by colonising, his grandfather had been a king and his father was a chief. But he himself was destined not for royalty but for revolution.

After Methodist boarding schools where they sang God Save The King, he went to the only black university in South Africa, Fort Hare. He began to rebel against authority and was expelled.

While living in a poor township in Johannesburg, and working as a security guard and then as a clerk at a law firm, he met the ANC activist Walter Sisulu and made friends with liberals and communists.

Nelson Mandela: "It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die"

After experiencing racism at the University of Witwatersrand, he joined the African National Congress in 1944 and helped establish its youth league. Together with a group of young, intelligent and highly motivated colleagues, including Mr Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, he set about transforming the ANC into a mass political movement.

Freedom charter

For much of the 20th Century, two vast monoliths had provided South Africa with its ruling elite: the National Party and the Dutch Reform Church. Their creed was based on an idiosyncratic Afrikaner reading of the Bible, with the Boer community cast in the role of the Chosen People.

The origins of apartheid - apartness - went right back to the very beginnings of European rule in Southern Africa, but it was only with the election of the first National Party government in 1948, in a white-only ballot, that racial segregation was thoroughly codified in law.

In legal terms, apartheid had three main pillars:

The Race Classification Act, which classified every citizen suspected of not being European according to race.

The Mixed Marriages Act, which prohibited marriage between people of different races.

The Group Areas Act, which forced people of certain races into living in designated areas.

In the early 1950s Mr Mandela toured South Africa, organising campaigns of mass civil disobedience.

Charged under the Suppression of Communism Act in 1952, Mr Mandela received a suspended prison sentence and was later banned from public meetings and confined to Johannesburg for six months.

He went on to produce a new organisational plan for the ANC, which broke it up into underground cells.

At the same time, he opened the country's only African law firm. His friend and biographer Anthony Sampson said of him at this stage that he was an impressive dresser who drove an Oldsmobile, and despite his political activity, "he seemed to me to be a bit of a showman really. I didn't take him seriously enough".

Archive: Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu were held at Robben Island

"I hadn't realised quite the steel that lay beneath because he was a very romantic, handsome, impressive character," he said.

In 1955, Mr Mandela played a key role in writing the ANC's Freedom Charter, which stated that South Africa belonged "to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people".

The following year, he was among 156 political activists, including much of the ANC's leadership, to be arrested and charged with treason. After a trial that lasted four-and-a-half-years, all the accused were eventually acquitted in 1961.

But the National Party upped the stakes drastically when, in 1958, it introduced the Pass Laws which restricted the movement of people classified as black or coloured (mixed race).

On the run

A key point for Mr Mandela came two years later, when 69 people were shot dead in a protest against the Pass Laws, an event which became known as the Sharpeville massacre, external. Days later, the government declared a state of emergency and banned the ANC.

Hundreds of political activists, including Mr Mandela, were arrested and detained without trial.

Not long afterwards, Mr Mandela spoke about turning to an armed struggle: "There are many people who feel that it is useless and futile for us to continue talking peace and non-violence against a government whose reply is only savage attacks on an unarmed and defenceless people."

Revolution was to follow. Mr Mandela told the ANC: "The attacks of the wild beast cannot be averted with bare hands only."

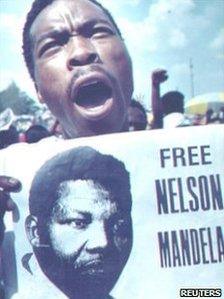

The campaign to free Nelson Mandela spread around the world

In 1961, South Africa left the Commonwealth after rejecting the idea of majority rule and reconstituted itself as a republic.

Mr Mandela, now out of prison, told an audience of 1,400 in Pietermaritzburg that, unless the government opened negotiations for a democratic future, there would be a national strike.

Government intransigence and a muted response to the call for a strike led to Mr Mandela going underground. The ANC began to advocate violence and Mr Mandela was made commander of its newly formed military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe.

The group's policy was to attack property - under his auspices, the ANC carried out a sabotage campaign, blowing up government pass offices, electricity pylons and attacking police stations.

However, in his autobiography Mr Mandela makes it clear they were prepared to go further and engage in guerrilla warfare and even terrorism. He grew a beard in the Castro style.

Worldwide campaign

On the run, Mr Mandela adopted a series of disguises including those of a chauffeur and a gardener. He travelled outside the country looking for support, but was arrested in South Africa in 1962 and was jailed for five years.

Two years later, Mr Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment for organising sabotage at what became known as the Rivonia trial. He was sent to Robben Island jail.

His story could have ended there.

Both he and the ANC had been effectively neutered, Western governments continued to support South Africa's apartheid regime and change seemed as far away as ever.

But the rise of the militant Black Consciousness Movement during the 1970s and the death in custody of one of the movement's founders, student activist Steve Biko, rekindled interest in Mr Mandela and the ANC.

Under apartheid, black and white South Africans were not allowed to mix

As the black townships went up in flames, an active worldwide anti-apartheid movement was growing, focusing on the express aim of freeing Nelson Mandela and his fellow prisoners.

Sanctions, demonstrations and music concerts - including one held on Mr Mandela's 70th birthday in 1988 - were just a few of the many ways that his plight was kept in the public eye.

South Africa became more isolated, businesses and banks refused to do business with it and the clamour for change increased.

In 1990, the South African government, which had already begun to water down some aspects of apartheid legislation, finally agreed to open negotiations, and Nelson Mandela was released.

He easily won the election in 1994 and became South Africa's first black president, by which time apartheid had been dismantled.

South Africa's people were now equal under the law and could vote, and live, as they wished.