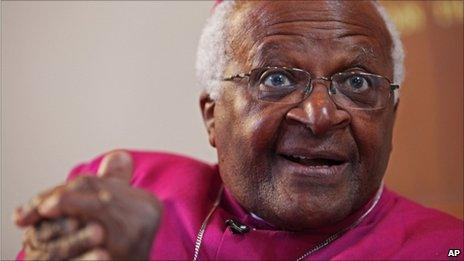

Profile: Archbishop Desmond Tutu

- Published

Desmond Tutu argued tirelessly that apartheid was against God's will

Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe may have described him as "evil", but Archbishop Desmond Tutu remains a much-loved figure across the world - principally for his role in South Africa's struggle against apartheid.

During the long years that Nelson Mandela was in prison, Archbishop Tutu spoke out against the regime - and won the Nobel peace prize in 1984 for his efforts.

He was chosen by President Mandela to chair South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission and investigate the crimes committed by all sides during the apartheid regime.

At 78, "the Arch" - as he is known - has remained irrepressible and influential both in his native South Africa and on the global political stage.

He is chairman of a group of former world leaders called The Elders, launched on Nelson Mandela's 89th birthday in 2007 with the aim of tackling some of the world's most pressing problems.

Early days

Desmond Tutu was born in 1931 in a small gold-mining town in the Transvaal. He first followed in his father's footsteps as a teacher, but abandoned that career after the passage of the 1953 Bantu Education Act, which enforced separation of races in all educational institutions.

He joined the Church and was strongly influenced by many white clergymen in the country, especially another strong opponent of apartheid, Bishop Trevor Huddleston.

Desmond Tutu became the first black Anglican Dean of Johannesburg in 1975.

He was already a high-profile Church figure before the 1976 rebellion in black townships, but it was in the months before the Soweto violence that he first became known to white South Africans as a campaigner for reform.

Inevitably, his pleas for justice and reconciliation in South Africa drew him into the political arena - but he always insisted that his motivation was religious, not political.

The churchman constantly told the government of the time that its racist approach defied the will of God and for that reason could not succeed.

Speaking out

Desmond Tutu was elected Archbishop of Cape Town in 1986.

As the first black head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, he continued to campaign actively against apartheid.

In March 1988, he declared: "We refuse to be treated as the doormat for the government to wipe its jackboots on."

Six months later, he risked jail by calling for a boycott of municipal elections.

Archbishop Tutu warmly welcomed the liberalising reforms announced by President FW De Klerk soon after he took office in 1989.

These included the lifting of the ban on the African National Congress and the release of Mr Mandela.

'Appalled at the evil'

In November 1995, the then President Mandela asked Archbishop Tutu to head a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. His task was to gather evidence of apartheid-era crimes and to recommend whether people confessing their involvement should receive amnesty.

At the end of the Commission's inquiry, in August 1998, he attacked South Africa's former white leaders, saying most of them had lied to the Commission.

He was often overcome by the pain of those who had suffered and said that he had been "appalled at the evil we have uncovered".

The Commission's report was accepted by the government, but was criticised by those who felt it fell a long way short of its aims.

Archbishop Tutu was accused, for instance, of being too soft on Winnie Mandela, who faced allegations of very serious crimes.

His experience in setting up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has led many governments and organisations to enlist his help for similar projects.

He advised non-governmental groups seeking reconciliation in Northern Ireland and has been invited to the Solomon Islands to help set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission there.

Zimbabwe 'basket case'

In recent years, Archbishop Tutu has been an outspoken critic of Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe, saying he had become "a cartoon figure of an archetypal African dictator".

In December 2008, he called on President Mugabe to resign or risk trial at the International Criminal Court.

The Archbishop accused Mr Mugabe of ruining what he called a wonderful country and turning it from a "bread-basket" into a "basket case".

He has repeatedly said that using force should be an option to get rid of Mr Mugabe and has criticised the South African government of being too soft on Zimbabwe's leader.

In his role as the chairman of The Elders, Archbishop Tutu continues to lend his support to conflict-resolution efforts across the world.

In October 2008, he travelled to the divided island of Cyprus, where the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot leaders had begun negotiations to try to reunify the island. He tried to encourage members of both communities to back the talks.

The Nobel laureate was also central to international efforts to calm the political crisis which engulfed Kenya after the 2006 election.

The archbishop met the two rival political leaders, Raila Odinga and Mwai Kibaki, to help persuade them to talk.

A power-sharing deal was reached a month later, with the two party leaders agreeing to the formation of a coalition government. However, wrangling over government posts continued for months.

Stinging criticism

Israel is another country to come under attack from the outspoken clergyman.

He has accused Israel of practising apartheid in its policies towards the Palestinians, and described Israeli blockades of the Gaza Strip as an "abomination".

On a visit to the Middle East in 2002, he said he was "very deeply distressed", adding that "it reminded me so much of what happened to us black people in South Africa".

Former US President George W Bush and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair also felt the sting of the archbishop's criticism, when he urged them to admit they had made a mistake in waging an "immoral" war in Iraq.

In an article for BBC News in February 2009, he wrote: "It would be wonderful if, on behalf of the nation, [President Barack] Obama apologises to the world, and especially the Iraqis, for an invasion that I believe has turned out to be an unmitigated disaster."

Tackling poverty

His criticism is not confined to politics, either.

In the wake of the furore over the ordination of gay bishops in the Anglican church, he accused the Anglican communion of allowing its "obsession" with homosexuality to come before serious action to end world poverty.

"God is weeping" to see such a focus on sexuality, he said, adding that the Church was "quite rightly" seen by many as irrelevant on the issue of poverty.

Most recently, he has urged governments affected by the global economic downturn to remember less well-off societies when considering cuts in overseas aid.

"Can you imagine what the impact must be on those who have been, in any case, on the margins of international society?" he said speaking on a visit to Ireland on 15 February.

"We belong together, and protectionism does not work... It is self-defeating."