Q&A: Kenya's constitution referendum

- Published

Opinion polls indicate most people back the proposed constitution, but there are some powerful figures in the 'No' camp

Kenyans are voting in a referendum on a new constitution - part of an agreement that ended deadly clashes after disputed elections in December 2007.

There has been some violence during the campaign - most notably a grenade attack on a Church-organised "No" rally in the capital Nairobi, which left six people dead in June. Some fear more clashes could break out.

What is wrong with the current constitution?

It gives a lot of power to the president - a legacy of Daniel arap Moi's 24-year rule.

This was blamed for many of the excesses of his time - for example, giving him the power to hand out public land to influential individuals.

Land has been a sensitive issue since independence in 1963 and has inflamed ethnic tensions.

Mr Moi's successor, President Mwai Kibaki, won a landslide victory in 2002 promising to change the constitution within 100 days of taking office. He said he would devolve power and thereby reduce corruption.

However, it has not proved easy. He failed in his first attempt to introduce a new constitution, which would have introduced the role of prime minister.

It was rejected in a referendum in 2005, in which current Prime Minister Raila Odinga successfully led the "No" campaign against his erstwhile ally. That campaign essentially became a referendum on Mr Kibaki's time in office.

What are the key proposals of this draft?

Basically, it intends to reduce the power of presidents and other national politicians, by giving more powers to local leaders.

It would create a second chamber of parliament - the Senate, which would be able to check the president's powers - and 47 counties with executive governors.

Unlike the current system, cabinet ministers would be appointed from outside parliament - and their numbers limited to 22.

The draft would allow voters to recall MPs if they were not performing their job adequately.

There would also be a land commission and any land illegally acquired could be repossessed.

There would be no position of prime minister, which was introduced as part of the current power-sharing arrangement.

Are there any other contentious issues?

Yes - mainly religious ones.

The constitution retains Kadhi courts, which deal mainly with matters of marriage and inheritance among Kenya's Muslim minority.

They have been in existence since independence but recently, in a case brought by Christian Churches, a court ruled they were discriminatory.

An abortion clause has also proved divisive, with religious leaders and politicians opposed to the draft arguing it provides a loophole for abortion in the future.

These issues have led some Churches to mobilise Kenyans to vote "No" in the referendum.

Is the constitution likely to be passed this time?

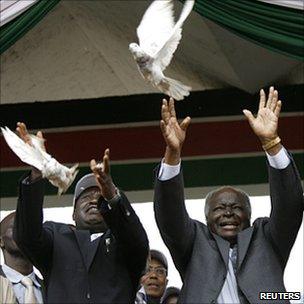

Raila Odinga (l) and Mwai Kibaki (r) are both campaigning for a 'Yes' vote

Opinion polls indicate that most people support the proposed constitution - the only question is whether it will get an overwhelming majority.

The relationship between coalition partners President Kibaki and Prime Minister Odinga has improved recently and both back the constitution.

But they have powerful rivals in the "No" camp - among them Retired President Moi (one of Kenya's largest land owners), most Christian Churches and Higher Education Minister William Ruto.

Once a key ally of Mr Odinga, Mr Ruto is keen on distancing himself from the prime minister and cementing his support in the Rift Valley where much of the 2007-2008 violence took place.

Will the referendum be peaceful?

That is the hope. But as well as June's deadly grenade attack on the Nairobi "No" rally, several MPs including Mr Ruto have been charged with hate speech during the campaign.

Tension is especially high in the volatile Rift Valley Province, which is home to most of the "No" campaigners, including ex-President Moi and Mr Ruto.

Land is the main issue here. Disputes over land between rival ethnic groups were behind some of the most violent incidents after the December 2007 election.

Once more, ethnic and political divisions overlap, with many Rift Valley residents whose origins lie elsewhere in Kenya likely to support the constitution, while local groups oppose it.

The government has deployed a special force of 10,000 officers to the area to prevent any violence.

Optimists say the hate speech charges brought against the politicians will act as a deterrent to anyone thinking of stirring up trouble.

- Published15 June 2010

- Published13 June 2010

- Published25 May 2010