Al-Qaeda exploits Sahara state rivalries

- Published

Western armies have conducted several military exercises to help the region tackle the Islamist militants

Islamist militants in the Sahara Desert are exploiting differences between neighbouring countries to continue to roam around the lawless region unhindered.

The killing of French hostage Michel Germaneau by al-Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the continued threat to other hostages still being held, has cast these differences into sharp relief.

The factions of AQIM that operate in the Sahara zone, and the Sahel region just to the south, move between Mauritania, Mali, Algeria and Niger.

The area is vast, sparsely populated and barely controlled by the region's security forces.

Northern Mali is especially easy for AQIM to operate in and the Sahara factions tend to spend most of their time there.

All the governments in the zone agree that given the group can easily cross borders, the response to their presence must be a co-ordinated one.

First European intervention

That is not happening, however, according to Adam Thiam, a columnist for Le Republican newspaper in Mali's capital, Bamako.

"A comprehensive regional response has been compromised because of the misunderstandings between the states concerned," he says.

The attack by French and Mauritanian forces on al-Qaeda in northern Mali last week to try to free Mr Germaneau was a new development in the region.

France, as well as other European nations and the United States, have been training soldiers here for many years.

This is the first time, however, they have admitted to being involved in an operation against AQIM.

'Principle'

The operation was conducted with Mauritania, which has been taking a tougher line with the Islamist militants recently.

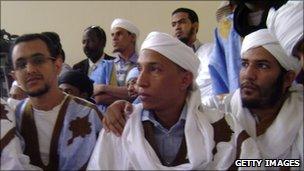

Mauritania has refused to release al-Qaeda suspects

Mauritania has been putting militants on trial, making efforts to secure its desert borders and has refused to negotiate with AQIM over hostages.

AQIM reportedly wanted some militants held in Mauritania freed in return for Mr Germaneau.

The Mauritanian defence minister said in June that his government would never do such a deal.

"We won't free any terrorist. It is a matter of principle. This would jeopardise the security of our country and our people," Hamadi Ould Baba Ould Hamadi told the AFP news agency.

This policy is in stark contrast with that of Mali.

Diplomatic row

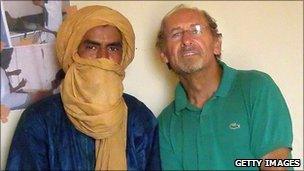

In February Mali released four prisoners it was holding accused of links to al-Qaeda, to secure the release of another French hostage.

Pierre Camatte (r) was released after four suspected militants were set free in Mali

France agreed to and indeed pushed for the deal.

It sparked angry protests from Mauritania and Algeria, however.

Both countries withdrew their ambassadors from Bamako for an extended period.

Official sources in Bamako say that Mali was not consulted before last week's Franco-Mauritanian raid, even though the raid took place on Malian soil.

Accords have been signed between the countries of the region that allow one country to cross borders during hot pursuit, but usually countries should keep each other informed.

Algeria vs the West

It is clear Malian officials are annoyed.

Given this was a special forces operation, France and Mauritania may have decided not to inform Mali of the raid simply to ensure that word of their plans didn't leak out.

There is no doubt, however, that both Mauritania and the government in Algiers would like to see Mali do more to secure its territory

But there is also a sharp dividing line between Algeria and Mauritania.

Algeria wants Western nations to stay out of the battle.

It wants any initiative against the Islamists to be strictly regional and preferably led by its forces.

The Algerians refused to take part in joint military exercises organised by the United States earlier this year.

Instead, Algiers set up a joint military headquarters in the southern Algerian town of Tamanrasset to help coordinate efforts against AQIM and the growing problem of drug smuggling in the Sahara Desert.

French revenge?

While the countries of the region have failed to act, al-Qaeda has been able to grow, says Mr Thiam.

"Al-Qaeda has managed to expand over the last few years and it's now becoming much harder to move against them."

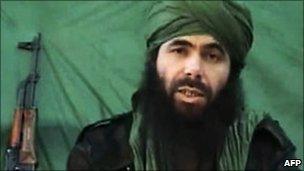

Abu Musab Abdul Wadud is believed to lead about 500 fighters based in the Sahara Desert

Although there are these differences in approach between the countries, other analysts see a different reason for the lack of action against AQIM.

Jeremy Keenan from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London says that some of the countries in the region have a vested interest in keeping Islamist militants in the zone. He cites the example of Algeria.

"The only country that could do anything about this problem is Algeria. And there are elements within the Algerian secret service that want to present Algeria as indispensable for the West in the region and for that you need to have a real threat."

So what happens next? Two Spanish hostages are still being held by AQIM.

There is still hope for them as they are being held by a different, some say less hardline, faction of the group. Spain may still be able to negotiate their release with a mix of cash and other concessions.

Announcing Mr Germaneau's death, France's President Nicolas Sarkozy promised that it would not go unpunished.

Could this mean more military action backed by France? Could the countries of the region use this opportunity to launch major operations against the group?

AQIM are not thought to number more than 500 fighters and some military analysts say that scaled up special forces operations could be highly effective.

However, taking the fight to AQIM is far from risk-free.

The group has shown that it can attack targets in Algiers and Nouakchott and already the French and US embassies here in Bamako have issued warning to their nationals telling them to be on the alert in case of any retaliation for the events of the last few days.

- Published26 July 2010