Nigeria: Still standing, but standing still

- Published

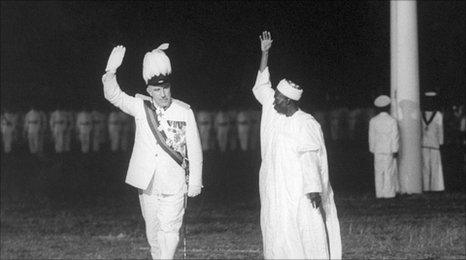

Nigeria's new prime minister Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa and the British representative James Robertson in the moment of Nigeria's independence

"As the clock struck midnight, [they] took their positions on the dais and watched the lowering of the Union Jack and the hoisting of the Nigerian flag... And so ended 100 years of British rule... 100 years of colonial bondage... A nation conceived in faith and unity is born today... And I am happy. And I am sobbing..."

There it was in cold, hard print in the 1 October, 1960 edition of the Daily Times newspaper. An emotional commentary written by Babatunde Jose, the publication's editor at the time.

The Daily Times, which had been founded in the 1920s, was the oldest and thought to be the most distinguished publication in Nigeria at the time.

And Mr Jose, who joined it as a 16-year-old trainee, and subsequently became known as "the grandfather of Nigerian journalism", went on to praise Nigeria's new leaders for embracing parliamentary democracy and committing themselves to uphold the rule of law.

He also confidently declared that the 1960 constitution and existence of a "powerful opposition party" (the Action Group, headed by Obafemi Awolowo) would protect diverse ethnic groups - and the country as a whole - from dictatorship and human rights abuses.

In 2008, aged 82, Mr Jose died and it is true to say that he lived to see his dreams collapse.

Tragically, the rot had set in long before the first decade of an independent Nigeria had drawn to a close, as the country succumbed to multiple dysfunctions and was plunged into a bloody civil war.

Having observed such negative developments with mounting alarm, Mr Jose was eventually eased out of his editor's chair in 1976 by Gen Murtala Mohammed's military regime, which had no use for his passionate idealism and belief in press freedom.

The newspaper limped on for a few more years and then finally sank without a trace, thanks to the incompetence and dishonesty that its government handlers persistently inflicted on it.

Disillusioned and disappointed

The demise of the newspaper is perhaps symptomatic of the wider leadership problems that have dragged Nigeria down and today robbed it of benefits like sturdy infrastructure and a reliable electricity supply (and all the attendant pressures this has put on Nigeria's economy today).

Matthew Tawo Mbu danced until dawn on Nigeria's independence day

Mr Jose is not alone. Many others have endured a plethora of bitter disappointments in the 50 years since Nigerians celebrated their liberty.

Chief Edwin Kiagbodo Clark - an 83-year-old veteran activist from the oil-rich Niger Delta region and a former finance minister - is one of them.

Mr Clark was a politically active school principal and staunch nationalist on that October day in 1960. He describes his mood then as being "completely elated". Today, however, he is disillusioned.

One of the things that has saddened him most over the past 50 years has been the gradual abandonment of the principle that Nigeria's different regions should develop at a different pace, and grow their economies in different ways.

Back then, Mr Clark laments, every region had its own plans for generating revenue internally via agriculture and other activities. But that widespread desire to be as productive and self-sufficient as possible no longer exists.

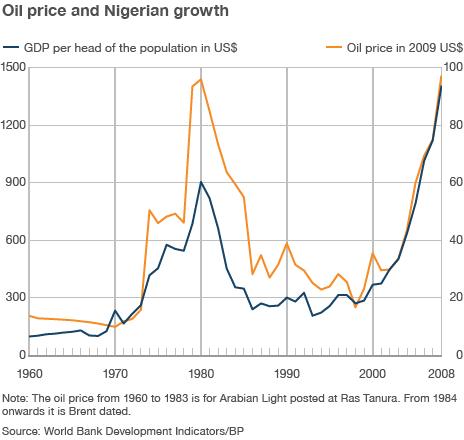

"Now, the Federal Capital Territory [Abuja] and most of the 36 states that have been created are almost solely dependent on the oil money that is distributed by central government. This status quo is simply not good enough," he says.

Mixed blessing

And indeed, the "oil curse" is a recurrent grievance.

Eighty-year-old Matthew Tawo Mbu, who was minister of state for defence on independence day, remembers that he and his colleagues had danced until dawn.

Before he joined Balewa's cabinet he had been the Nigerian high commissioner to London and in 1957 had been invited to the Dutch city of Rotterdam to ceremonially discharge the first consignment of Nigerian crude oil to the country.

"We had absolutely no idea, at the time, that oil would become such a major source of income," he says.

"And it has been a blessing because it enabled the country to amass a fortune. But the expectations some of us had have not been matched.

"Corruption, which has increased in magnitude since 1960, has given us a rotten image internationally and prevented us from fulfilling our potential in areas like social welfare and infrastructural development."

Others mourn the seeming loss of critical self-awareness in the country. Deborah Ajakaiye, Nigeria's first female geophysicist and Africa's first professor in the field, was a student at the University of Ibadan in 1960.

"There was so much excitement on campus. We were so full of hope."

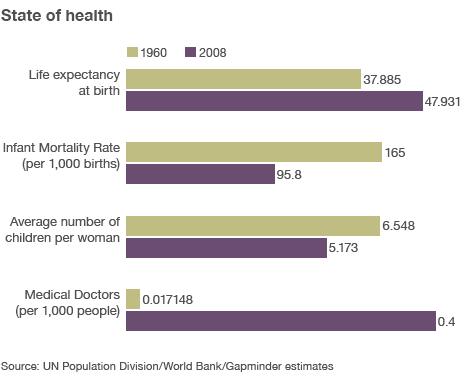

But for Ms Ajakaiye, Nigeria has deteriorated on several levels since then: Educational institutions have been seriously weakened, the railway sector is dead and the country's value system has been deeply compromised.

"Murders which used to be extremely rare are now commonplace," she says

"[And] the acquisition of ill-gotten wealth has also become more acceptable."

Back then if someone built a mansion that was not compatible with his salary, the entire community would query it with him.

"Now, very few questions are asked," she tells me.

Turning tide?

But there is much that Nigeria can be proud of.

For instance, in contrast to the fate of the Daily Times, today the country can boast an array of media organisations and a generally free press.

In addition, there has been impressive growth in industries like aviation and telecommunications, and a recent announcement that much of the country's power sector is to be privatised could be the answer to Nigeria's electricity woes.

The tide could be turning against corruption, too. Recently, the removal of two senior figures on the Nigerian Stock Exchange followed on from a warning by the country's market regulator, Arunma Oteh, that hundreds could face criminal charges for corruption.

And according to a recent editorial in the This Day newspaper, Nigerians can feel justifiably satisfied about their contribution to security in Africa including its peacekeeping efforts in Sierra Leone and a noteworthy role in dismantling apartheid in South Africa.

There is one achievement, however, that may be worth elevating above all.

In the context of the myriad of problems faced by Nigeria over the past 50 years, somehow, miraculously, the country has succeeded in staying in one piece.