Nigeria's emirs: Power behind the throne

- Published

Traditional leaders continue to exert considerable influence in Nigeria

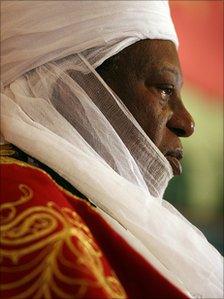

Praise-singers and drummers herald the arrival of the emir of Zazzau in the northern Nigerian town of Zaria.

Resplendent in his flowing red robes and turban, he is surrounded by courtiers and advisors, and protected from the sun by a large white ceremonial umbrella. Palace guards stand to attention as he passes.

In its turbulent half-century of independence, Nigeria has experienced not only a brutal civil war, but also a succession of military coups.

Only in the last decade has it enjoyed relatively stable civilian government.

Throughout this period, one institution that has played an important stabilising role has been that of the traditional rulers of kingdoms large and small across the country.

While traditional leaders hold few constitutional powers, no politician is wise to seek office without his blessing.

In pre-colonial days, kings ruled with absolute power across what is now northern Nigeria. Their origins pre-date even the arrival of Islam some 200 years ago.

Under British rule, these northern emirates were adopted as an integral part of the colonial administration and they became increasingly powerful.

Electoral impact

Today, despite attempts by successive governments to marginalise them from the political process, traditional leaders continue to exert significant influence.

The emir says his role is to bring peace to communities

"They continue to yield so much power in who gets what political appointments, although most of this influence remains behind the scenes," explains Kabiru Sufi, a political scientist.

This remains so particularly in the mainly Muslim north, where they are seen as custodians of both religion and tradition.

In one of Kano's largest markets it was difficult to find shoppers who disagreed with that sentiment.

"I trust my traditional rulers because they don't loot our money," one man told us, reflecting a widely held disillusionment with the elected political class in Nigeria.

Another says: "I trust them because they choose quality politicians who will help the people, and I'm happy to vote for the candidates they advise."

These sentiments are particularly pertinent at a time when political aspirants are jockeying for selection as party candidates ahead of local and national elections in just a few months' time.

Golden throne

At the emir's palace, a horn is sounded as he enters the inner royal chamber.

A succession of local dignitaries approach him, now seated on his golden throne, to pay their respects.

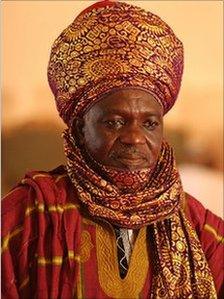

When independence came to Nigeria, Shehu Idris was a school headmaster.

But with his royal lineage he was destined for another calling.

For more than three decades, he has been the emir of a kingdom with its palace in the town of Zaria, and influence over a much larger region known as Zazzau.

We have been granted a special audience, and approach the royal throne.

Nigeria's kingdoms used to rule with absolute power in pre-colonial days

Little has changed in terms of protocol and tradition in such courts for many centuries.

What role does he see for traditional rulers in today's Nigeria?

"It is for us to intervene in disputes to bring peace to communities," he says.

When it comes to elections, "we don't give support to politicians. We give them blessing, that they should have respect and be ready to serve the people who have elected them."

It is easy to be cynical, and to object that Nigeria's recent history has been both chaotic and violent.

Or to suggest that politicians in Nigeria are held in such low regard that any idea that they enter politics to serve anything other than their own pockets, sounds faintly ludicrous.

But the moral certainty of values the emir upholds are genuine and widely respected and traditional beliefs, both spiritual and religious, are powerful forces in Nigeria.

With the audience over, the trumpet sounds and the court herald declares the session at an end.

Along with his many advisors, we withdraw from the room leaving the emir alone on his golden throne.