UK seeks China aid partnership in Africa

- Published

China has become a formidable force in Africa

Britain is seeking a new partnership with China as a key to speeding up development and ending poverty in Africa.

In recent years, China has become a formidable force in Africa, investing billions of dollars in exchange for trade and raw materials that China needs to fuel its own booming economy.

This has sparked intense debate as to whether China should be seen as a predatory neo-colonial influence that bypasses issues such as human rights, or a welcome help for hard-up Western governments struggling to meet their commitments to international aid.

Now Britain's International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell has clearly said that China's involvement should be embraced.

"We are looking to work very closely with China," he told BBC News.

"And those discussions have already started. That is a high priority for the coalition government. In partnership with China we will be able to do much more to speed up development in Africa."

Western governments have been giving aid to Africa for decades, yet millions there still live in poverty.

Britain's aid budget is protected from pending spending cuts because of a UN commitment, but how it is spent is coming under increasing scrutiny.

Building up Tanzania

Britain is one of the biggest donors to Tanzania, a country that has had no real conflict or famine.

With a third of Tanzania's 41 million people living below the poverty line, Britain is spending more than £130m there this year.

But many Tanzanians are now looking at China's focus on trade and the economy as a key to moving them forward.

One third of Tanzania's 41 million people live below the poverty line

"We need infrastructure, infrastructure, infrastructure," says Emmanuel D Ole Naiko, executive director of the Tanzania Investment Centre.

"The Chinese are building roads, railways, factories. They are extracting coal and minerals. They are directing their investments so they can make this child grow."

Just about everywhere in the commercial capital, Dar es Salaam, you can see evidence of the Chinese at work.

They are building luxury apartments in anticipation of a Chinese-style economic boom; drawing up renovation plans for a railway they first built in the 1970s; and putting up a cardiac wing in a main city hospital.

There, more than 30 Chinese engineers and technicians run teams of Tanzanian workers.

Unlike workers with Western companies, the Chinese expatriates do not demand expensive perks such as housing, school fees and flights home.

They live on-site until the job is finished.

The unit will take a year to build and will be equipped and staffed by Chinese doctors.

'No strings attached'

Not far away, at the Sino-Tanzania Friendship Hospital that opened two years ago, Chinese doctors and pharmacists deal with local patients at highly subsidised rates.

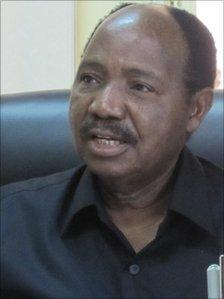

"We get money from the Chinese that is cheaper with less conditions and for projects that Western donors consider to be too costly," says Tanzanian finance minister Mustafa Mkulo.

"One is a coal power project that will produce enough electricity for the southern part of Tanzania."

Many Chinese projects come in the form of soft loans that Mr Mkulo says are between 1.5% and 2%, far undercutting finance offered by the West.

Throughout Africa, China makes it clear that its deals come with "no strings attached".

While Western governments demand benchmarks on issues such as human rights, democracy and good governance, China lays down no such conditions.

"We treat African countries as brothers and sisters, as equal partners when we provide aid and assistance," says the Chinese ambassador to Tanzania, Liu Xinsheng.

"Assistance should not be used as a tool to intervene in the internal affairs of your friends. We will not impose anything on them."

Chinese take-over?

Mustafa Mkulo says there is a role for both China and the West

Britain remains one of the leading donors and trading partners with Tanzania.

According to the Tanzanian Investment Centre, it has carried out more than US$1.5bn (£940m) of trade in the past 10 years, creating almost half a million jobs.

In comparison, China's trade is valued at US$620m (£390m), but it is rising fast.

Both Tanzania and Britain insist, however, that there is no argument for China taking the place of the West.

"We need both," says finance minister Mr Mkulo.

"There is no crowding. The Chinese are developing a certain part of the country. The West has its own interest."

Britain's development secretary says Chinese involvement will not enable the government to cut the more than £7bn aid budget.

"I could spend the British development budget three times over," says Mr Mitchell.

"There is huge need out there. We need every penny. But from our partnership with the Chinese will come a very healthy development approach towards Africa."

But in much of Africa, they talk about the politics of aid, remembering the divisions created through aid given by the Soviet Union and the West during the Cold War.

Many are waiting to see if there can be a genuine partnership with China. Or - as in the past - whether it will turn out to be a competition for influence between more powerful countries.