'Little Mogadishu': Paradise for shoppers or pirates?

- Published

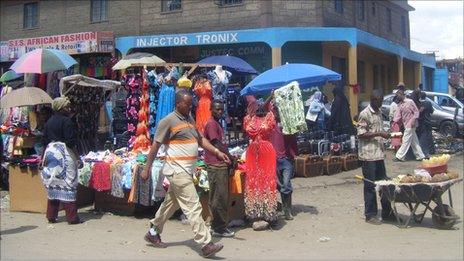

Eastleigh sells everything imaginable, attracting buyers from across East Africa

The predominantly Somali district of Eastleigh in Kenya's capital Nairobi is seen by many as a haven for Somali pirates and Islamist extremists, and as a place for them to invest their money.

But despite its bad reputation and appalling infrastructure, it is one of the most popular shopping areas in the city because the prices are low and the range of goods is enormous.

People come from all over East Africa to shop in Eastleigh: from different parts of Kenya, Somalia, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Southern Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The relationship between Kenyans and Somalis is not an easy one, even though many Somalis have Kenyan citizenship; the vast North-Eastern province of Kenya, which borders Somalia, has a predominantly ethnic Somali population.

Things have become especially difficult since the rise of violent Islamist extremism in Somalia.

Kenya feels threatened, not only by Islamist groups in Somalia, but by the potential threat of home-grown extremism within the Kenyan Somali community.

'ATM machines'

The police regularly swoop on Eastleigh, rounding up people they say are illegal immigrants, even though many of them turn out to be Kenyan citizens of Somali ethnicity.

In the latest incident, some 400 people were picked up last weekend.

The arrests came days after a suspected grenade attack in Eastleigh, which killed one police officer and injured another. The authorities said the security sweep had nothing to do with the grenade explosion.

A taxi driver who took me to Eastleigh - also known as Little Mogadishu - said: "Somali pirates come to Nairobi to buy expensive houses in the best districts. Kenyans hate Somalis, but they are very good at business."

But it is becoming increasingly difficult for Somalis to do business in Kenya.

Earlier this year, the Kenyan central bank directed financial institutions in the country to monitor the transactions of Kenya-based Somalis suspected of having links with Somali insurgents such as al-Shabab, which has links to al-Qaeda.

Kenya has reason to be nervous.

Al-Shabab controls the area of Somalia that borders north-eastern Kenya. In September, Kenyan police leaked to the media documents containing details of an al-Qaeda cell in East Africa. The documents said dozens of young men in Kenya had joined the cell, received training in Somalia, and were plotting an attack on Kenya.

"Do you know what the Kenyan police call Somalis?" asked a successful Somali businessman, who asked not to be named.

"They call us ATM machines. That's because the only way we can navigate the situation here is to bribe the police at every turn."

To make life easier, he has a non-Somali business partner, and he says he never uses his name when dealing with the authorities because it would be "commercial suicide".

Angry traders

It is not only Somalis involved in big business who have problems with the Kenyan authorities; small-scale traders in the Eastleigh shopping malls also complain of harassment.

Abdirashid says claims that local Somalis have links with al-Shabab and pirates are "rubbish"

There are numerous different shopping centres in Eastleigh. Inside, the Olympic Shopping Centre, my eyes took time to adjust to the darkness inside. It was a warren of kiosks, selling everything imaginable.

There were filmy mini-dresses hanging next to burkas made from dark, heavy cotton. There was extraordinarily-shaped ladies' underwear in colourful cotton and intricate nylon lace. There were children's shoes, sunglasses, mobile phones, vacuum cleaners.

The traders called out to me, welcoming me to sample their wares.

But when they discovered I was a journalist, things went cold. The traders started shouting at me, saying they would not speak to me because journalists always insinuated that they were linked to pirates or al-Shabab, and that all the new buildings going up in Eastleigh were built with pirate money.

They complained that unscrupulous Somalis in Eastleigh tricked foreign journalists by posing as pirates or former Islamist fighters, granting interviews in exchange for money.

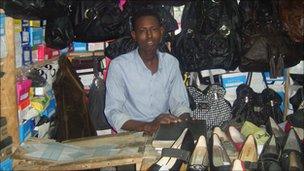

I eventually persuaded one young man, Abdirashid, to speak to me.

Sitting in his kiosk, surrounded by handbags and shoes, he dismissed all talk of pirates and Islamist extremism: "The stories about us being connected with al-Shabab and the pirates are complete rubbish. Somalis were here in Eastleigh years before the pirates and al-Shabab even existed."

Ahmed Abdisamad Elmi, a journalist from the Eastleigh-based Somali radio station, Star FM, had a theory about why Somalis had such a bad name in Nairobi.

"Eastleigh has become one of the biggest markets in East Africa. Some people are very jealous of what we have done so they spread propaganda to disgrace the Somali people," Mr Elmi said.

"Even though Somalis don't get on with the authorities, they get on with ordinary Kenyans because we teach them how to do business and how to make money. We have done a lot for this country."

Mountains of rubbish

Eastleigh residents have stopped paying local taxes, complaining about inadequate public services

Apart from problems with the police, Somalis in Eastleigh suffer from extremely poor infrastructure. You can tell as soon as you enter Eastleigh because the tarmac stops.

Vehicles try to dodge deep potholes, but there are so many of them that driving a car through Eastleigh feels like riding a lame horse up and down a steep and rocky mountain.

Crowds of shoppers navigate their way around stinking mountains of uncollected rubbish, hopping over open drains. Electricity and water supplies are erratic.

So bad is the provision of public services that this year residents of Eastleigh stopped paying local taxes. Their decision was backed by a court.

Despite the difficulties encountered by Somalis in Kenya, they continue to do business in a vibrant, unique and enterprising way.

With no end in sight to the trouble in Somalia, it is likely that the number of Somali refugees will increase in Eastleigh and other parts of Kenya.

Together with the Kenyan Somalis, it is likely that they will keep playing a significant role in the Kenyan economy regardless of the obstacles put in their way.

- Published6 December 2010