Can Sudan's oil feed north and south?

- Published

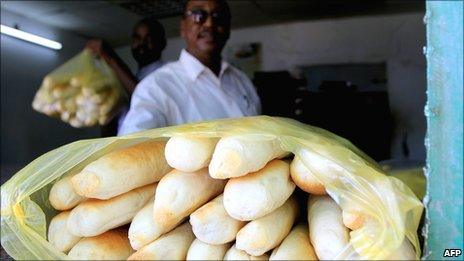

The oil has meant that food shortages have become a thing of the past

Oil has fuelled conflict in Sudan, and rapid growth in the northern heartland of Africa's biggest country, as the 4x4s purring past shining skyscrapers in the capital, Khartoum, suggest.

But when South Sudan becomes independent, it will take most of Sudan's oil with it.

"The most important thing about southern secession is what will happen to the oil revenues," says Rosie Sharpe of the campaign group Global Witness, which has released a report on the country's oil wealth, external.

"Without a new, equitable oil deal between north and south, it is difficult to see how southern separation could pass off peacefully."

An estimated two million people died in a two decade long north-south civil war which often flared most fiercely around oil fields in the south.

Most of Sudan's oil is produced in the south, but exported through the north

But some Sudanese now hope that rather than creating a new war, this time the precious resource could lubricate a peaceful future between the two states.

Since a 2005 peace deal, the south and the north split southern oil revenues equally - and almost three-quarters of the daily 500,000 barrels output comes from the south.

The north's economy will take a mighty hit when the south secedes.

According to Global Witness, oil revenues accounted for 50% of domestic revenue and 93% of Sudan's exports in 2009.

Already prices for food and basic goods are rising, as the government scales down on subsidies it feels it will no longer be able to afford.

'Deluded'

In public the northern authorities are optimistic.

Nafie Ali Nafie, a close ally of President Omar al-Bashir and a former head of national security, said that those who spread rumours that the economy in the north would collapse due to the south's secession were "greatly deluded".

He said southern independence will have "no impact" on the economy of the north which has "many alternatives in agriculture and minerals".

In private, the northern leaders are panicking - it is simply not possible that losing so big a part of the economy will not have consequences.

The spectre of food riots and angry street demonstrations, a vivid memory for many Sudanese, is a worrying one.

But the south's reliance on oil - which provides 98% of its revenue - makes it tremendously vulnerable too.

If the oil stops flowing, the southern economy would collapse.

The 85% of its people who live from agriculture might not be directly affected, but the state would be unable to pay its soldiers, and instability would undoubtedly be the result.

The almost $10bn (£6.5bn) the south has received in oil revenues since the 2005 peace agreement have paid for some improvements to roads and infrastructure.

But many people say they have seen little benefit from the petrodollars, and South Sudan remains one of the least developed regions on earth.

Nevertheless oil money is the region's one real earner, so it is vital the oil keeps pumping after separation.

South Sudan remains one of the least developed regions on earth

The South Sudan government has said it will respect deals that have already been signed.

Some oil executives have already moved down to the southern capital, Juba, from Khartoum.

But, crucially, the pipeline to export the oil goes to Port Sudan, in the north.

This, it is hoped, will encourage the two putative countries to work together.

There has been talk of a new pipeline to Kenya, but this would be extremely costly and would take years to build.

Untapped reserves?

In the ongoing negotiations, resources are a key topic, and it seems likely the south will agree to pay a hefty fee to use the north's pipeline.

It has even been suggested, by Luka Biong - until recently a southern minister in Sudan's federal government - that the south might continue to give Khartoum a share of the oil revenue for some time.

Alsir Sidahmed, a Sudanese journalist who specialises in oil, sees some positive signs of co-operation.

"In August [2010] an oil deal was signed in block E, which extends over both the north and the south," he says.

"The main concessionaries are Spanish and Norwegian companies, but Sudapet and Nilepet - the companies of the north and south - are taking 10% each.

"The north and south are getting into an oil deal which will last for 25 years."

In the long term, the south will need to diversify its economy away from oil.

"Without additional discoveries, it is estimated that output will peak in the 2011-12 year and then gradually decline thereafter and is likely to run out in 20 to 30 years," said Dirk-Jan Omtzigt, during his recent period as an economic adviser at the Joint Donor Team, set up by six donor nations to support the south after the peace deal.

There may well be untapped reserves in the south, but if they are in swampy or difficult terrain they could be costly to extract.

In the short to medium term, the oil is the southern economy's only chance.

The hope is that a mutual interdependence will keep the north and south from fighting.

"If north and south can reach an equitable deal as to how they will co-operate over oil, the shared oil revenues could give a strong incentive for keeping the peace, as they have done over the past five years," says Ms Sharpe.

But she has a warning.

"Transparency of the oil revenues is paramount to ensuring that any new oil deal stands the tests of time."