The male beauty contest judged by women

- Published

Make-up, flirting, bling outfits. But this beauty contest has a twist - the men dress up, the women pick the winners. What does the Wodaabe people's pageant tell us about male beauty?

Tall, slim, facial symmetry and good teeth - this could be the universal tick list of a beauty pageant judge.

And when the contestants are men, their faces painted with red, white and yellow clay, the aesthetic holds true.

These unusual beauty contests, known as Gerewol, celebrate the fertility the rains bring to the parched edge of the Sahara. Filmed for the BBC's Human Planet, Niger's Wodaabe men decorate their faces and dance for hours to impress female judges - who may take them as lovers.

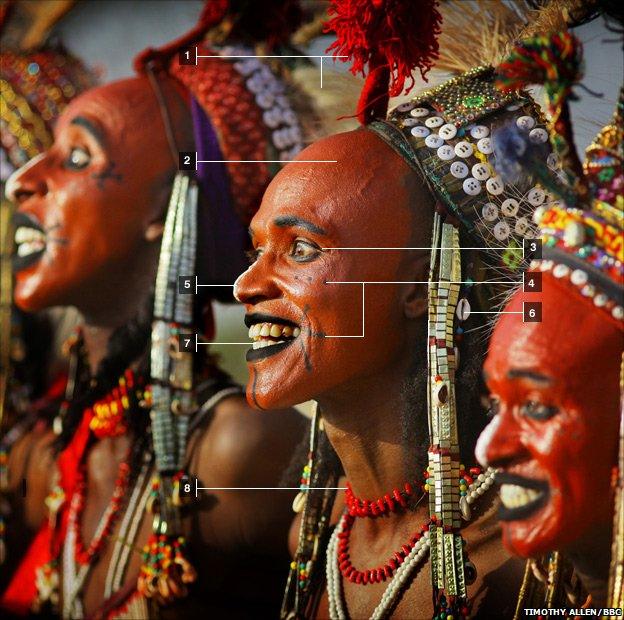

Lipstick and beads may be associated with femininity in Western eyes, but the ceremonial costumes aim to emphasise male beauty:

Tall and athletic: Ostrich plumes and pompoms emphasise height

Narrow face: Decorated with red ochre

Wide eyes: Black eyeliner made from charred egret bones

Facial symmetry: Enhanced with black, yellow and white patterns

Aquiline nose: White clay arrow stripe to look more streamlined

Long braids and cowrie shells: Symbolise fertility and wealth

White and regular teeth: Bared and emphasised with black lipstick

Good dancer: Beaded necklaces and bodices jangle against chest in time to the beat

The colours used are symbolic too, says Mette Bovin, a Danish anthropologist who has worked with the Wodaabe since the 1970s.

Red ochre, which coats the face, is associated with blood and violence and so only used on special occasions. Yellow clay, used by some dancers to paint patterns on the face, is the colour of magic and transformation.

And black, to darken lips and emphasise eyes, is a favourite hue, partly because it is the opposite of white - the colour of loss and death, says Bovin in her book Nomads Who Cultivate Beauty, external.

Adding to the black lipstick's significance, it is made from the charred bones of the cattle egret, a bird the Wodaabe associate with "expressivity", says Bovin. "To have charm - that is to have expressivity and charisma - is highly valued in a young man."

The dance moves emulate the poise of the egret, and the men sing by vibrating lips painted with this "bird-lipstick", as Bovin describes it.

And the prize? Each judge chooses her champion and may take him as her lover - even if both already have partners - and the winners are celebrated for years to come. Nor is the potential for match-making limited to judges and winners.

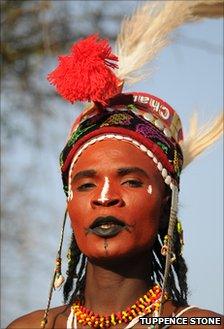

Djao dressed to impress, but didn't win. He and Tembe stayed together

"You dance Gerewol to try to win a lover, even if it means stealing someone's wife," says contestant Djao, who met second wife Tembe at a previous Gerewol. "You can marry her, or have a fling with her."

She, too, is on the look-out. "I've spotted three men here that I like."

No stigma is attached to setting aside one's marriage vows at Gerewol whether temporarily or permanently, says Human Planet director Tuppence Stone.

"The initial marriages in Wodaabe culture are arranged when the bride and groom are very young, so Gerewol is the chance for a love match," she says. This is not a polygamous culture - marrying a new partner means leaving the old.

Drought, conflict and, more recently, insurgency from al-Qaeda's North African offshoot means this traditional celebration is rarely practised - except at tourist hotels in eastern Niger, where Wodaabe troops may demonstrate the dances.

For the clans filmed by the BBC, who live in small, nomadic groups on the borders of Chad and Niger, it was their first Gerewol after six years of drought. Only when there is enough water to support several hundred people in one place do the normally isolated Wodaabe gather.

Human Planet: Deserts will be broadcast on Thursday 20 January at 2000 GMT on BBC One, and will also be available on the BBC iPlayer.