Tunisia's famous avenue leads the way to change

- Published

International editor, La Presse: 'Change has been so huge and rapid that we wonder if we are dreaming'

On the elegant boulevard named after Tunisia's founding father, a new chapter of history is being written.

Habib Bourguiba Avenue, once the place to see and be seen, has become the place to speak and be heard.

A Tunisian-style "Speakers' Corner" has emerged, one week after the momentous upheaval termed the "Jasmine Revolution".

After weeks of pitched battles here with security forces, it is now a place of forceful - but peaceful - arguments over the future of this North African nation.

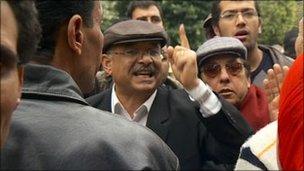

All along the tree-lined promenade, Tunisians huddle around orators who have found their voice and the freedom to air their views.

It is a scene that would have been unthinkable and illegal under the 23-year repressive regime of President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, which collapsed when he was forced to leave his country last Friday.

'Breathing freedom'

Tunisians are debating their country's future in a way that would not have been possible even a week ago

In one spot, a dishevelled man holds up a placard with RCD scribbled all over it in bold black print. He shouts, to appreciative cheers, that the RCD former ruling party must be completely eliminated.

A few steps away, another speaker in a traditional brown woollen cloak holds the attention of a cluster of men and women as he argues that all political groups, from communists to Islamists and even remnants of the RCD, must now be allowed to participate in political life.

The French-style cafes dotting both sides of the avenue are now front-row seats in the capital's main open-air political theatre.

Hamadi and Lotfi sit on wrought-iron chairs under a striped canvas awning, taking a coffee break from the protests they have been part of from the start.

"We're breathing freedom now," Hamadi declares.

As we speak, a crescendo of chanting rises and falls as protestors march past. "RCD Degage!" (RCD Clear Out!) is one of the main rallying cries for thousands of demonstrators who also converge on this avenue from all directions, and all walks of life.

"The RCD will go," Hamadi insists. "Believe me, they will disappear."

Just around the corner is the "Fleet Street" of Tunis, home to many of the capital's main newspapers, where journalists have kicked out editors who were handpicked by the old regime.

Salem Mekki, of the former ruling RCD, says the party should still be allowed to play a role in the country

In the offices of La Presse, the oldest state-run newspaper, I find International Editor-in-Chief Hmida Ben Romdhane sitting in his cramped, glass-walled office, still stunned by the changes.

"Its like night and day, black and white," he marvels. "The changes of the last week have been so huge and rapid, we think we are dreaming."

A stack of old newspapers provides black and white proof. Every front page is adorned with a photograph of President Ben Ali or his wife Leila Trabelsi. She, and other members of "the family" are reviled in the protests for their lavish lifestyles.

Across a narrow corridor, Rafik Hergan stares at his computer screen. His next article is written except for the last word in its headline, which starts in French 'Le temps de" (The time of).

"Yesterday, the word was 'The time of change'. Now I need to think of a new one," he muses, still deep in thought. "We have to be sensitive and reasonable," he cautioned. "Everyone was connected to the past so we must be as open as possible."

The sound of the protests on Habib Bourguiba Avenue wafts through the open windows as he sits at his clunky white desktop computer.

'Demonised'

There's a dizzying pace of change in Tunisia, with every day bringing new measures to dismantle the old order.

Leading members of the old guard are still in power. They hold key posts in a new national unity government, but ministers from the RCD have been forced to leave the former ruling party.

In a small office inside one of the city's classic white stucco buildings, I met Salem Mekki, a senior RCD member who insists the party is being "demonised".

"If Tunisia is building a democracy, how can you eliminate a million people?" he asks, rhetorically.

Mr Mekki, who belonged to the party's now dissolved central committee, is arguing for rehabilitation and reform. "Those who committed mistakes must be tried, and pay. Those who didn't must have the right to serve their country," he says.

Back on Habib Bouguiba Avenue, I run into a gaggle of bankers in fine suits. They have come out of their offices to join the protests.

"We don't accept the idea that only the RCD has the experience to run this country," says one.

It is hard to walk here without being stopped every few steps by Tunisians eager to share their opinions.

At the very end of this avenue is a barricade of coils of razor wire manned by soldiers who still stand at the ready. But Tunisians stop to take photographs and offer coffee to a force widely seen as protectors.

Riot police, viewed as an appendage of the ousted regime, can be seen strolling along the avenue, holding helmets and shields under their arms.

If Habib Bourguiba Avenue is a microcosm of this historic change, it augurs well for the peaceful transition many Tunisians would like to see unfold.