Somalia: Counting the cost of anarchy

- Published

Somalia has not been under the control of a single national government since 26 January 1991, when military strongman Siad Barre was toppled. What impact has 20 years of war and instability had on Somalia and its people?

The conflicts

During the 1990s, the conflict in Somalia was between rival warlords and clan-based militia. This led to widespread hunger and the UN and US intervened before a humiliating pull-out.

Fighting continued but with less intensity until in 2006, the Union of Islamic Courts became the first group to exert control over the whole of the capital, Mogadishu, for 15 years.

Ethiopia then invaded to oust the Islamists, with US support. But the Ethiopians were unable to exert control and now the capital is the scene of regular battles between the UN-backed government and the al-Qaeda linked militants, al-Shabab.

About 1.4 million people are displaced within the country - mostly in southern and central areas, around Mogadishu.

The north has been relatively peaceful, especially the former British-run territory, Somaliland. Although its independence is not internationally recognised, it runs democratic elections and last year saw a peaceful transfer of power - still a rarity for Africa.

Neighbouring Puntland runs its own affairs but says it wants to remain part of Somalia. Many of the pirates who have taken advantage of the anarchy to hijack ships for ransom in the busy shipping lanes off Somalia's are based in Puntland port towns, such as Eyl.

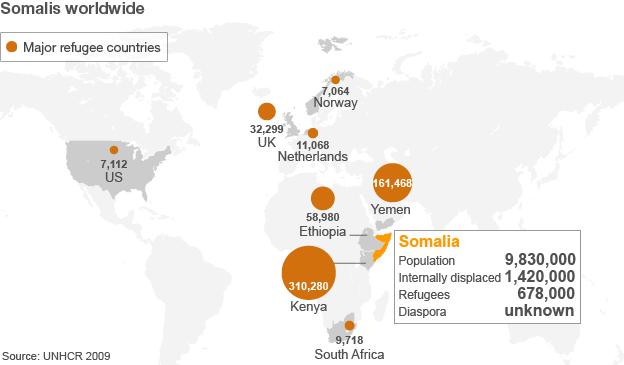

Refugees

Civilians have borne the brunt of the conflict, with more than two million fleeing their homes - 20% of the population.

Some 678,000 have officially been accepted as refugees in foreign countries while thousands more have fled their devastated homeland to live abroad.

There are more than 600,000 registered Somali refugees worldwide, adding to a diaspora of settled Somalis who are believed to number more than one million.

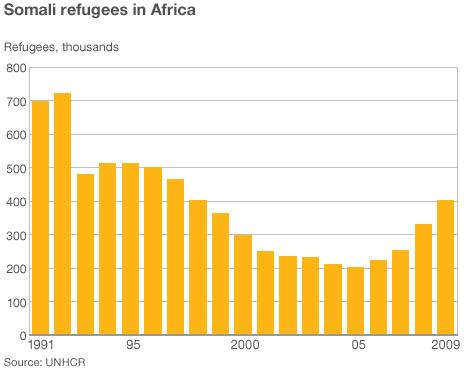

This enormous migration has occurred largely during the last 20 years. A major exodus took place during the civil war which ousted Siad Barre in 1991.

In the following decade, many refugees returned to Somalia from neighbouring countries. But since 2005 a new exodus has begun - triggered largely by fighting between Islamists and government forces.

Living standards

Remarkably for a country which has suffered two decades of conflict, living standards have slowly improved.

Somalia remains poor in relation to most African countries, but its economy and its people have found ways to get by without a government.

Somalia's GDP has risen steadily throughout the last two decades, as has its life expectancy. And while neighbouring countries have been hit hard by the HIV/Aids epidemic, Somalia has largely escaped.

Although health facilities remain poor in most regions, the chances of a newborn child surviving to its first birthday have actually increased slightly since 1991.

Sources: CIA/UN/UNICEF

The figures in the table above do not tell the full story. The relative stability in living standards may in part be because of the work of international aid agencies.

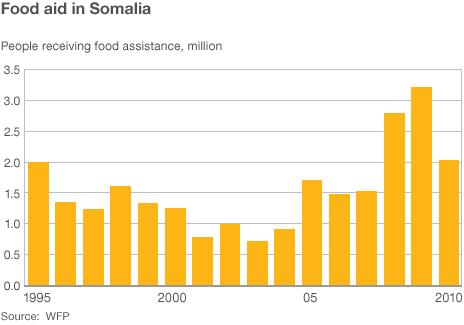

Throughout some of the worst periods of conflict, Somalia has still received assistance with food and health.

These figures from the UN World Food Programme show that food aid has increased in recent years, coinciding with a period of fighting between Islamists and forces loyal to the Somali government.

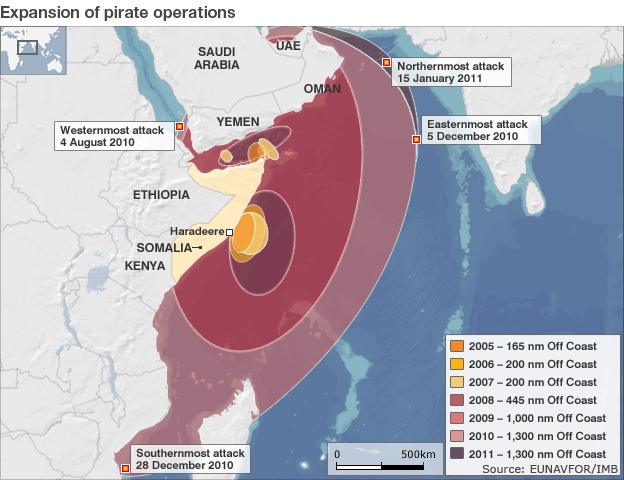

Pirates

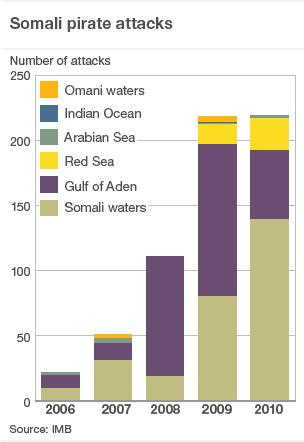

Without any law enforcement and with few other ways of earning their living, piracy has become an attractive option for many young Somali men in recent years.

They earn millions of dollars for each ship they successfully seize.

Warships from around the world have been sent to deter attacks by patrolling off the Somali coast.

But the pirates have responded by travelling further and further afield - some ships have been hijacked closer to India than Somalia.

All the experts agree that the only long-term solution to the problem of piracy is to restore law and order on land.

But a succession of donor-funded peace conferences has failed to persuade the rival Somali leaders to put down their weapons and work together.