Kalahari Bushmen in 'remarkable' legal victory

- Published

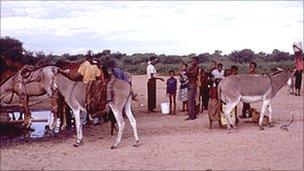

The Basarwa Bushmen are traditional hunter-gatherers who have lived in the Kalahari for generations

An appeals court in Botswana has ruled that indigenous Bushmen can drill wells for water on their traditional land in the Kalahari Game Reserve.

The judgement is a remarkable victory for the Bushmen.

Not only has the court upheld their right to water in the Kalahari Desert, but it has criticised the government's treatment of the bushmen as "degrading".

Supporters of the Basarwa Bushmen inside and outside Botswana are greeting the court of appeal's judgement as a victory for the rule of law.

Survival International, the London-based organisation which campaigns for the rights of indigenous peoples and has strongly backed the Bushmen's legal battle, described the appeal court's decision as "momentous".

Survival's Director, Stephen Corry, said: "This is a great victory for the bushmen, and also for Botswana as a whole. We hope it will be embraced as such by the authorities."

Ever since 1997, when the government of Botswana decided to move the Basarwa off their ancestral hunting-ground in the Kalahari, the Bushmen's battle to return has been a losing one.

Shanty towns

In 2002 the army moved the majority of the Bushmen out of the Kalahari, often brutally, but some refused to leave. Others drifted back from the soulless shanty towns where they were forced to live.

For tens of thousands of years, the Bushmen have managed to live and thrive in this deeply hostile environment. The British, who were the colonial power in Botswana before its independence, promised it to them in perpetuity.

The Botswana government's decision to move the Bushmen followed the discovery of diamonds in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), the heart of the Bushmen's territory. It has often been alleged that the two things were linked, though successive governments have denied this.

The legal battle focused on a single well, on which those Bushmen who still lived in the CKGR depended for their water.

The army blocked up the pipe with concrete and filled the basin with sand: A melancholy sight in this inhospitable desert.

Nevertheless the Bushmen managed to survive without the well. They found water in their traditional ways, and sometimes they managed to raise the money to buy bottled water from a store 30 miles (48km) away.

The Basarwa found ways to survive in the desert without a well

On at least one occasion, as a group was returning from the 60-mile walk carrying hundreds of bottles, they were stopped by guards at the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, who poured all the water on to the ground.

The 2010 judgement, which the appeal court has now reversed, was criticised inside and outside Botswana for its tone.

The presiding judge then, Judge Walia, said that the Bushmen had "brought upon themselves any discomfort they may endure".

Many of the Bushmen's supporters saw this as part of a wider, more vindictive attitude. The former president of Botswana, Festus Mogai, has often been quoted as calling the Bushmen "stone age creatures".

Botswana is in many ways a model African country - wealthy, democratic and not obviously corrupt. But even its supporters have been embarrassed by the treatment of the Bushmen.

Now, if the government of President Seretse Khama Ian Khama shows it accepts the ruling, Botswana can turn the page and allow the bushmen their ancient rights again.

- Published27 January 2011

- Published21 July 2010