Uganda's Museveni pulls out all the stops to stay in power

- Published

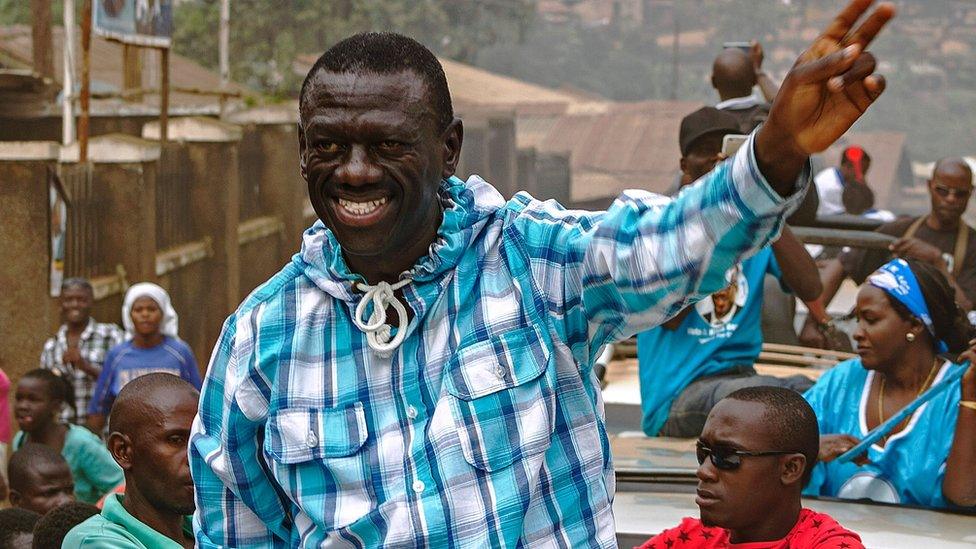

The opposition has been able to campaign more freely this time round

Even before the first vote has been cast in Uganda, the cries of foul play from the opposition have already started.

For many people, the big question is not whether President Yoweri Museveni will win but how the opposition will react to what it describes as a sham.

Democracy in Africa is once again under the spotlight.

A shambles in Ivory Coast followed by street power in North Africa have dominated headlines in recent weeks, and it is no coincidence that Uganda's main opposition candidate, Kizza Besigye, has been saying the word "Egypt" a fair few times at his rallies.

For the incumbent, it is fairly vital he sails through in the first round.

If the ruling National Resistance Movement candidate does not pass the crucial 50% mark, he could face a significant struggle to win against a combined opposition vote in a run-off.

In previous elections, his popularity has steadily slipped. He secured over 75% of the votes in 1996. By 2001, 69% of votes were for Mr Museveni, and the winning tally in 2006 was down to 59%.

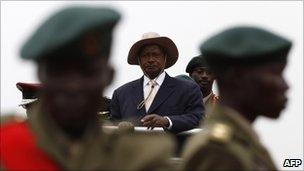

President Museveni still has considerable support - partly because he is seen by some Ugandans as the man who restored peace after years of turmoil in the 1970s and 1980s.

Army factor

However, after being in State House for 25 years, there is growing discontent with the man who once said that the problem with African leaders was overstaying in power.

Yoweri Museveni says only he is able to keep Ugandans safe

Creating a bloated patronage system and failing to deal with corruption are two common criticisms of his government.

The message which President Museveni has worked hard to instil in Ugandans minds is: "I brought you stability. The other candidates can't keep you as safe I can therefore vote for me."

Many Ugandans are also starting to feel that - so long as Mr Museveni is unwilling to give up the seat - there is little point in trying to get rid of him. The sense is that he (rather than Uganda) has a rather large army and he is not afraid to use it.

Unlike 2006, this election has so far been without major drama.

Dr Besigye of the Forum for Democratic Change has not been hounded by the terrorism and rape charges which he faced during the last campaign - charges which were widely seen as trumped up and may well have gained him votes as he was portrayed as the victim.

Following defeat at the previous two elections, Dr Besigye went to the courts but the judges upheld Mr Museveni's victory.

Dr Besigye insists that the electoral commission is firmly under the control of the governing party. He also says this time the courts are not an option.

Dr Kizza Besigye: 'We are participating in this election knowing it is not free or fair'

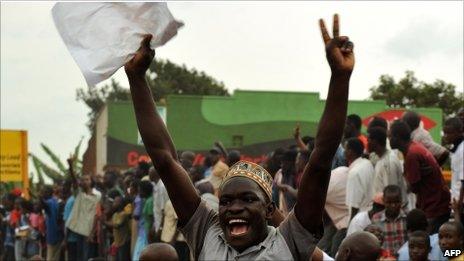

"Instead we'll have to look for other ways. Obviously one of the ways is to get the people to protest," he told the BBC ahead of the vote.

"How Museveni intends to deal with it is very clear: He has deployed his troops across the country armed to the teeth so he hopes to clearly use force to quell whatever kind of protest comes up.

"We will want to see to what extent the government wants to become criminal by gunning down its citizens who have not committed any offence," Dr Besigye added.

Scramble for cash

Whether a significant number of Ugandans would have the stomach to take part for long in what would be a very one-sided game of street power is doubtful.

"I have the right medicine for those who want to cause trouble," Mr Museveni has said.

A recent highly visible street presence of the police and army also sends out a powerful message.

It has been suggested that money rather than oppression of the opposition has been a key tactic in this race.

All politicians need money for campaigns, but the ruling NRM seems to have very deep pockets this time around and has been dishing out the shillings to the electorate.

Some call it legitimate mobilisation funding. Others see it as downright bribery.

When a minister's car was involved in a crash at the weekend, the local media reported that it was ferrying 1bn Ugandan shillings ($420,000 £261,000) to be distributed on the campaign trail.

Villagers arriving at the scene helped themselves. Having seen their politicians steal their taxes for so many years, the looters felt no guilt.

This year the NRM is ensuring Mr Museveni wins at any cost. In January, the finance minister stated the government was broke.

At the same time MPs suddenly found an extra 20m shillings in their bank accounts.

Also in January, the government granted a 600bn shilling supplementary emergency budget and the allocation for State House shot up significantly.

It is not just the opposition that believes this splurge has been pumped into the Museveni campaign.

The stakes are especially high for this election as oil money should start to flow in the coming months.

Uganda is reportedly sitting on national reserves of 2.5bn barrels of oil, and there are plans to build a refinery which could boost the country's economic clout significantly.

Last term?

In the north of Uganda, for the first time in decades people are voting when there is peace.

Norbert Mao says northerners will not back Mr Museveni, even though the area is now peaceful

The Lord's Resistance Army rebels are still causing havoc in nearby countries but not in Uganda.

The peace dividend will help Mr Museveni gain votes in what has been a key opposition stronghold.

But the bitterness runs deep and many northerners still blame the current president for the misery they endured during the war.

Presidential candidate Norbert Mao believes Mr Museveni's gains in the north will not be dramatic.

"He did not protect the population. He dumped millions of people into camps and neglected them until the international community came.

"Now if you dump me in a deep pit and I suffer for 20 years, even if you get me out, the first thing I'm going to do is not say: 'Thank you' but ask: 'Why did you do this?'"

If he wins, will this be Yoweri Museveni's last term? Do not bet on it.

- Published17 February 2016

- Published17 February 2016