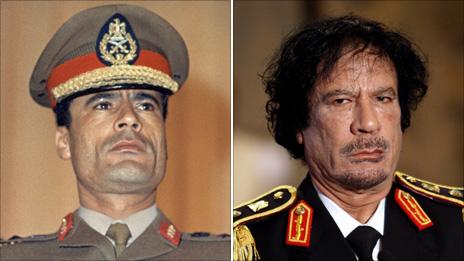

Gaddafi's quixotic and brutal rule

- Published

A military coup brought Muammar Gaddafi to power 40 years ago

Muammar Gaddafi came to power in Libya in September 1969 as the leader of a bloodless military coup which overthrew the British-backed King Idris.

He was 27 years old, inspired by Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser and he seemed to fit the regional template of Arab nationalist from the military becoming president. But he outlasted his contemporaries.

During nearly 42 years in power he invented his own system of government, supported radical armed groups as diverse as the IRA in Northern Ireland and the Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines, and presided over what may have been North Africa's most totalitarian, arbitrary and brutal regime.

In the last years of his rule, Libya emerged from the international isolation that followed the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie in Scotland in December 1988. The country was once again courted by Western governments and companies drawn to its vast energy reserves and the rich contracts on offer in an ambitious infrastructure programme.

The uprising that eventually overthrew him started in February 2011 in Libya's second city Benghazi, a city he had neglected and whose residents he mistrusted throughout his rule.

Jamahiriya

Col Gaddafi was born to a Bedouin family in Sirte in 1942.

He always played on his humble, tribal roots, preferring to greet visitors in his tent, and to pitch it when on foreign visits. His legitimacy depended on his anti-colonialist credentials at first, and then on keeping the country in perpetual revolution.

His stated political philosophy, expounded at length in the Green Book, was "government by the masses".

In 1977, Gaddafi proclaimed the Libyan "Jamahiriya" - a neologism meaning roughly state of the masses.

The theory was that Libya had become a democracy of the people, governed through local popular Revolutionary Councils.

In practice, all key decisions and state wealth remained tightly under his control.

Social theories

Gaddafi was a skilled political manipulator, playing off different tribes against each other and against state institutions or constituencies. He also developed a strong personality cult.

More and more, his rule became characterised by patronage and the tight control of a police state.

The worst period for Libyans was probably the 1980s, when Col Gaddafi experimented on his people with his social theories.

As part of his "cultural revolution" he banned all private enterprise and unsound books were burned.

He also had dissidents based abroad murdered. Freedom of speech and association were absolutely squashed and acts of violent repression were numerous.

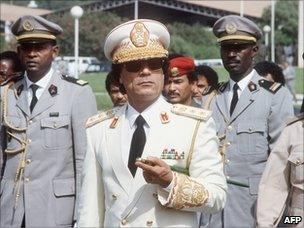

Col Gaddafi experimented on his people with his social theories during the 1980s

This was followed by a decade of isolation by the West after the Lockerbie bombing.

For Libyans critical of Col Gaddafi his greatest crime may have been the squandering of wealth on foreign adventures and corruption.

With a population of only six million and annual oil revenues of US $32bn in 2010, Libya's potential is huge. Most Libyans do not feel this wealth and living conditions can be reminiscent of far poorer countries.

A lack of jobs outside government means that unemployment is estimated to be 30% or more.

Libya's particular form of socialism does provide free education, healthcare and subsidised housing and transport, but wages are extremely low and the wealth of the state and profits from foreign investments have only benefited a narrow elite.

In 1999, the Libyan leader made a comeback from almost total international isolation when he accepted the blame for the Lockerbie bombing.

The demonstrations spread to Tripoli after after cities in the east appeared to fall to the opposition

Following 11 September 2001, he signed up to the US government's so-called "war on terror". Soon after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Libya announced that it was abandoning its nuclear and biological weapons programmes. Both of these were seen by his critics as highly cynical moves.

In the final years of his rule, as questions of succession arose, two of his sons seemed to be in open and damaging competition against each other for his favour.

The influence of Saif al-Islam, the elder son who took an interest in the media and human rights issues, appeared to be waning as the influence of Mutassim, who had a powerful role in the security services, grew.

Inspired by neighbours to the west and east, Libyans rose up against 40 years of quixotic and often brutal rule in early 2011.