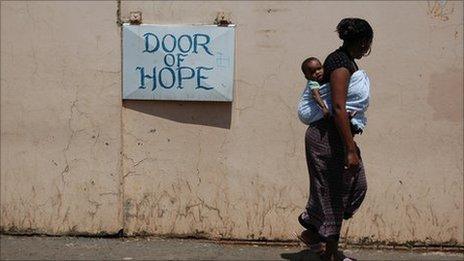

'Baby bin' to save South Africa's unwanted children

- Published

A Johannesburg orphanage says its baby hatch gives desperate mothers an alternative to dumping their babies in rubbish bins

Most people would not give a second glance to the metal hatch on a wall in Hillbrow Street in Johannesburg's tough Berea suburb.

But the "Door of Hope" is saving the lives of scores of unwanted babies.

Mothers can place their babies, usually newborn, inside and leave them anonymously to be found and cared for.

Once the infant is placed inside the "baby bin", sensors on the mattress set off an alarm.

"When that alarm rings you drop everything because you know there is a tiny baby in there fighting for his or her life," says a carer at the Door of Hope orphanage.

The child is then taken for a medical check-up.

"Some of the babies we get through the bin are healthy but others are not so lucky. Some are dehydrated, malnourished and underweight and we have to nurse them back to health," says Angela Kizobokamba, who works at the centre.

The baby hatch was opened in 1999 by a local church in response to the number of infants' bodies which were being found in the area every month.

To date, Door of Hope has received more than 960 children - 10% of which were left in the baby bin.

Berea has a reputation for crime, unemployment prostitution and drugs.

Child welfare workers here say the area's desperate social conditions, compounded by Aids, are the main reasons why so many young mothers abandon their children.

'A chance at life'

This boy is lucky to be alive after he was abandoned as a newborn

Inside the orphanage the carers are hard at work.

It is almost feeding time for some of the older babies - who are just over a year old.

The hallways are quiet, a group of women speak in hushed tones as they tip-toe past two neighbouring rooms. Inside, babies - some as young as two weeks - lie peacefully in their cribs.

These are the lucky few - they are alive and have someone to care for them.

And if the orphanage has its way, they will soon be adopted by families who can provide for them.

None of the children can be identified to protect the children and the identities of their birth mothers.

For the carers, feeding, bathing and playing with these children is a labour of love whose reward they say is knowing that they "loved the baby back to life".

Ms Kizobokamba says most babies are abandoned during the holidays, with Christmas and Easter being the busiest times of the year.

"Often the mother wants to go home for their holidays and they don't want their families to know that they fell pregnant so they come and leave them here," she says.

Life and death

One child is abandoned in Johannesburg each day and two in Soweto - a township south of Johannesburg, according to Door of Hope director Kate Allen.

"We've seen an increase in the number of children being abandoned. When we started, we got an average of four children per month but now we receive up to 16 children," says Ms Allen.

Child Welfare South Africa (CWSA) - the country's largest non-governmental organisation - says more than 2,000 children are abandoned in the country every year - a 30% increase in the past three years.

Many of them are found near death in rubbish bins, wrapped in plastic bags, inside toilets, shoe boxes, open fields and parks and often die within hours of birth from dehydration, starvation or hypothermia.

Many of the children cared for by the orphanage over the years have been well but some had to be put on anti-Aids drugs, after tests revealed that they were HIV-positive.

The orphanage has received criticism for the hatch over the years, with people saying it gives mothers an easy way out.

But Ms Allen rejects this criticism.

"By the time somebody finds these children, they are usually already dead. At least with this, mothers who can't keep their babies know that their child has a chance at life," she says.

"The reality is that whether there is a baby bin or not, young mothers are abandoning their children all over the country every day," says Ms Kizobokamba as she feeds a nine-month old baby at the home.

"What we do gives desperate mothers and their children an alternative."