Profile: Libya's Moussa Koussa

- Published

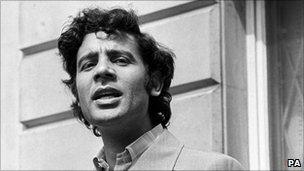

Moussa Koussa's loyalty to Col Gaddafi was not in doubt for decades

Libyan Foreign Minister Moussa Koussa's reported defection is a new twist in a political career stretching back more than three decades.

His arrival in the UK on 30 March in apparent flight from the embattled government of Muammar Gaddafi contrasts sharply with his appointment as the colonel's de facto ambassador in London in 1979.

In an interview for The Times in 1980, he advocated the killing of Libyan dissidents on British soil, telling the newspaper: "The revolutionary committees have decided to kill two more people in the United Kingdom. I approve of this" - though Tripoli later claimed he had been misquoted.

Having separately professed admiration for IRA militants fighting the British state, he was expelled from the UK.

The fiery radical then rose within Col Gaddafi's elite, first handling relations with foreign "national liberation" movements, then becoming his head of intelligence in 1994, only moving from that post to the foreign ministry in 2009.

As Libya's top spy, he was tasked with bringing a pariah state in from the cold, and played a key role in negotiating compensation for the families of victims of the Lockerbie and Niger airliner bombings, external.

On the eve of the Libyan revolt in February, Mr Koussa's efforts to rehabilitate Libya internationally appeared to have paid off handsomely, with oil trade links established across Europe and doors open to Col Gaddafi in Paris, external and Rome, external.

Reports suggest Moussa Koussa's persona has mellowed since the outspoken radicalism of 1980

But Mr Koussa's work had also brought him in close contact with intelligence services in the UK, say correspondents, and he had talked recently on the phone to British Foreign Secretary William Hague - perhaps explaining why the UK became his port of call once he decided to leave Libya.

Fading star?

Mr Koussa's association with Muammar Gaddafi is evident as early as during his studies towards a master's in sociology at Michigan State University in the 1970s, when he interviewed him for his thesis in a document some observers say reveals interesting details about the enigmatic Libyan leader.

"He was a very bright guy," Christopher K Vanderpool, Mr Koussa's thesis adviser and now chairman of the Michigan State sociology department, told the Los Angeles Times.

"If he had become a professor or a social planner, he would have done very well."

Mr Koussa was offered the chance to continue to study for a doctorate but instead returned to Tripoli to become "a strong man of the revolutionary committees, backbone of the Libyan regime and trusted aide of Muammar Gaddafi", as described by the AFP news agency.

According to an article in Britain's Observer newspaper, external, a confidential profile prepared by British intelligence in December 1995 described him as the head of the "principal intelligence institution in Libya, which has been responsible for supporting terrorist organisations and for perpetrating state-sponsored acts of terrorism".

However, he has never been formally charged with any of the attacks on Western targets attributed to Libya in the 1980s.

Guma El-Gamaty, an organiser in the UK for Libyan dissidents, told the Associated Press Mr Koussa "has been Gaddafi's right-hand man for years", and his apparent defection would be a "big hit".

Moussa Koussa announced a ceasefire earlier in March, after the UN resolution was passed

The BBC's world affairs editor John Simpson says that Mr Koussa has changed over the years, and when he met him during his tenure as intelligence chief, he mistook him for a junior minister, because he was "pleasant" and "inclined to come over and press the flesh at meetings".

Our correspondent says that Mr Koussa's star had in fact long been fading within Col Gaddafi's regime.

"The key thing is that he was on the out - Col Gaddafi got suspicious of the whole deal done with Britain [over Lockerbie], said it was a plot, and only went through it very reluctantly. Ever since, Col Gaddafi has been saying this was bad, that he was led into it.

"Moussa Koussa also had some kind of battle going on with one of Col Gaddafi's sons and I think he felt it was time to call it a day."

Perhaps in a sign of incredulity in Tripoli, Libya's government sought to deny reports of Mr Koussa's defection, with a spokesman telling Reuters that the foreign minister was "on a diplomatic mission".

The foreign minister himself was quoted by the UK government as saying he was "resigning his post", and it was not immediately clear if he intended to work actively against his former leader.

Whatever his future role, he would certainly be an invaluable source of information on Col Gaddafi's rule.