Ivory Coast's Laurent Gbagbo: From democrat to autocrat

- Published

The political trajectory of Laurent Gbagbo is that of a democratic reformist who became a dictator.

A history lecturer by profession, with a doctorate from a Paris university, Mr Gbagbo was crucial in Ivory Coast's transition toward multi-party democracy in the 1980s and early 1990s.

After becoming president in 2000, however, he adopted draconian measures to stifle political dissent and manipulated issues of nationality and religion to maintain power.

In his wake, he leaves a divided country that threatens the stability of the entire region.

For 33 years, Ivory Coast was ruled by its founding President, Felix Houphouet-Boigny, whose political moderation and close ties to the West initially brought stability and economic prosperity which were the envy of the continent.

Over time, Mr Houphouet-Boigny grew increasingly autocratic, corrupt and unpopular.

Plummeting cocoa prices in the late 1970s and early 1980s generated massive unemployment and political discontent.

Meanwhile, Mr Houphouet-Boigny began meddling in the affairs of neighbouring states, including supporting the 1987 coup against Thomas Sankara, president of Burkina Faso.

Jailed

In response, Mr Gbagbo became one of Mr Houphouet-Boigny's most strident opponents, calling for greater democratisation and redistribution of wealth.

Between 1971 and 1973, Mr Gbagbo was jailed for "subversive teaching" and "fomenting insecurity".

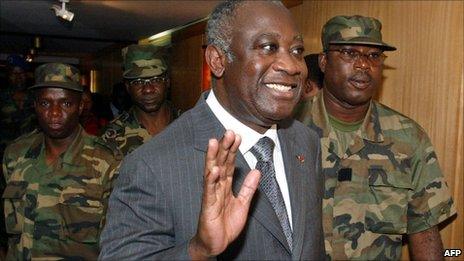

Laurent Gbagbo toppled Robert Guei and became president in 2000

After leading a national teachers' strike in 1982, he formed the opposition Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI) and demanded a shift toward multi-party elections.

Harassed by Mr Houphouet-Boigny's security forces, Mr Gbagbo went into exile in France later the same year, returning in 1988 to step up the pressure for democratic reform.

In 1990, Mr Gbagbo and the FPI succeeded in pushing Mr Houphouet-Boigny toward Ivory Coast's first national elections since independence.

Although Mr Gbagbo - the only presidential opponent - lost by a landslide in the heavily rigged vote, he won a seat in the National Assembly and continued agitating for political change.

This brought him a second spell in jail in 1992 - this time at the hands of the prime minister, Alassane Ouattara, who by then was effectively running the country as Mr Houphouet-Boigny's health deteriorated.

Mr Gbagbo's burning resentment toward Mr Ouattara for these years of imprisonment underlines much of the current conflict between the two leaders.

Mr Ouattara's actions during that period also call into question his democratic credentials and his ability to ensure stable governance following the 2010 elections.

The trappings of power

At great personal cost, Mr Gbagbo was a vital player in the opening up of Ivory Coast's democratic space.

The political contestation that Mr Gbagbo encouraged, however, turned increasingly divisive and violent following Mr Houphouet-Boigny's death in 1993.

With new political opportunities and the trappings of power came a dramatic shift in Mr Gbagbo's ideology.

In 1999, Robert Guei captured the presidency through a coup and quickly pushed through a national law requiring both parents of presidential candidates to be born within Ivory Coast.

This excluded major political opponents from contesting the presidential elections in 2000, including Mr Ouattara, whose father was born in Burkina Faso and who enjoyed enormous political support in the Muslim-dominated north of Ivory Coast.

This left Mr Gbagbo as the only viable opposition candidate.

With close parallels to the fraught election of 2010, Mr Gbagbo was recognised as the victor in 2000 but Mr Guei tried to use military force to cling onto power.

With support from elements within the army and massive street demonstrations, Mr Gbagbo toppled Mr Guei and was installed as president.

Like Mr Guei before him, for the next decade Mr Gbagbo manipulated tensions around nationality, citizenship and land rights to shore up his political control and marginalise opponents such as Mr Ouattara.

Mounting anger at these measures led to an attempted coup in 2002, when mutinous soldiers captured the northern towns of Korhogo and Bouake.

Poisonous rhetoric

Mr Gbagbo used massive force to put down the rebellion, leading to a disastrous civil war which split Ivory Coast in two, between north and south.

Mr Gbagbo blamed "outsiders", especially Burkina Faso, for fomenting the rebellion and employed a poisonous rhetoric about "Ivorians" and "foreigners".

For the next eight years, Mr Gbagbo exploited tensions between local ethnic groups and migrant workers in the cocoa industry, discriminating particularly against migrants from Burkina Faso.

Presidential elections slated for 2005 were postponed six times until Mr Gbagbo eventually agreed to them in 2010.

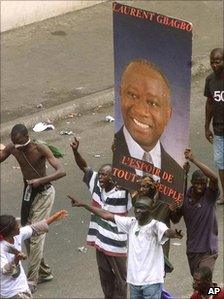

In the build-up to the vote, Mr Gbagbo again stirred up tensions around nationality and accused Mr Ouattara of not being Ivorian and therefore unfit to run for president.

Against these odds, Mr Ouattara won the election which was recognised internationally as free and fair.

Mr Gbagbo refused to accept the result, claiming widespread voter fraud in northern constituencies.

He ordered his troops to retain control of the presidential palace, state television station and the army barracks.

Months of stalled negotiations forced Mr Ouattara to seek a military solution, leading to pitched battles between Mr Ouattara's and Mr Gbagbo's troops in the streets of Abidjan.

With Mr Gbagbo finally arrested by his opponents after a long siege at his residential compound, for most Ivorians his historical role in fighting for democracy and the equitable distribution of wealth is now long forgotten.

Dr Phil Clark is a lecturer in comparative and international politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and convenor of Oxford Transitional Justice Research