Egypt protesters defiant over Mubarak

- Published

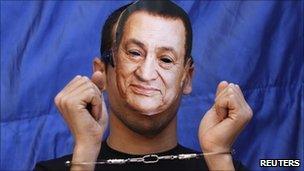

Protesters have made it clear how they feel about Hosni Mubarak

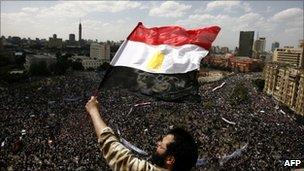

News that Egypt's former president, Hosni Mubarak, had broken nearly two months of silence spread fast among the large crowds of demonstrators in Cairo's Tahrir Square, but few were impressed by his message.

"Egyptians don't believe a word. We think Mubarak is a liar," said Tahir Abdul Zahir, standing on the edge of a new makeshift campsite.

"Maybe we will make a big protest again on Friday."

Mr Mubarak used an audio recording on Sunday on al-Arabiya television, broadcast with just a library photograph on screen, to deny corruption allegations and vow to clear his name.

"I cannot remain silent in the face of continued campaigns of lies... aimed at tarnishing the reputation of me and my family," he said.

After the long-time leader was forced out of power on 11 February, there were unconfirmed reports that he had amassed a personal fortune worth billions of dollars, much of it kept in overseas accounts.

In his statement, he insisted he only had money saved in an Egyptian bank.

One of the people gathered in Tahrir Square, Sharif Buri'e, said everyone regarded Mr Mubarak's words as a "big joke".

"I hope we can get him. We can talk about the money later but let's talk about the bloodshed first, let's talk about the corruption of our political system for the past 30 years."

Army rule

Egypt's public prosecutor, who has been investigating the killing of hundreds of protesters in the country's 18-day popular uprising and claims of misuse of public funds, has now summoned Mr Mubarak and his sons for questioning.

Yet nothing short of a prosecution will satisfy demonstrators who have remained in Tahrir Square since a mass rally on Friday. They withstood clashes with the army during their first night and continue to hold their ground.

Tahrir Square remains the focal point of protests in Egypt

"This really doesn't change anything," said one young woman passing through an informal checkpoint set up by the barbed wire now sealing off the busy intersection to traffic. "I think we will stay here."

Egypt's new military rulers will be disappointed by such comments.

There has been growing criticism of the army's handling of this key stage of political transition and its perceived failure to deliver justice.

Mr Mubarak appointed all of the generals of the Supreme Military Council, making many activists wary of their loyalties and commitment to reform.

Over the weekend, the army moved in to shift protesters from Tahrir Square, leaving one one protester dead and dozens injured. Such actions have only added to tensions.

One protester, Fawzi Radwan, now carries an effigy of military chief Field Marshal Tantawi around Tahrir Square to remind everyone of the weekend's violence.

"The military fired tear gas and rubber bullets to try to disperse us," he said.

"I got assaulted at 2.30 in the morning. Anyone who came in their way was beaten: women, children, old and young."

Although the army has made strong statements, warning it will use "firmness and force" to restore order and enforce a night-time curfew, it has seemed unwilling to carry out its threats.

"Now that the military has stepped from behind the curtain and is governing directly, it is inevitably facing friction with the people on a variety of fronts," said Elijah Zarwan who wrote an International Crisis Group report analysing the military's revolutionary role.

"The tug-of-war between a decentralised protest movement and a hierarchical institution whose first interest is stability, is likely to continue."

Away from Tahrir Square, many Egyptians are ready to give the ruling generals more time to fulfil their promises. There is recognition that while the military is the most powerful institution in the country it is scrambling to meet post-revolutionary demands.