Is Morocco next in line for mass uprisings?

- Published

Demonstrations are now a daily event in Rabat

Pro-democracy activists in Morocco are gearing up for more mass demonstrations this month, unsatisfied with the king's pledge to carry out "comprehensive" constitutional reform.

Inspired by the success of protesters elsewhere in North Africa, tens of thousands of Moroccans took to the streets on 20 February.

King Mohammed VI responded three weeks later, promising changes that would dilute his absolute hold on power.

The prime minister calls it a "peaceful revolution". But the protest leaders insist the proposals fall far short of their demands.

"Our first demand is a constitution for the people and by the people - a complete reform," says Montasser Drissi, one of the original group of young protesters.

The February 20th movement grew quickly via Facebook and is now calling for further rallies this Sunday and the following week.

'No Tahrir Square'

The king has ordered a committee to draft constitutional reforms which include making the prime minister elected, not appointed.

The proposals will then be put to a referendum. But the committee members were chosen by the king himself, convincing protesters that any changes will be superficial. So the demonstrations continue.

"It's good to keep the commission under pressure," explains Mr Drissi. "If the people want change and the king does not - he will be alone. He must listen to the people."

Many of those people are now trumpeting their demands all over the Moroccan capital.

You can barely walk a block in central Rabat these days without passing a protest.

Unemployed graduates are staging a sit-in outside parliament; hundreds of teachers have set up camp in front of the education ministry.

Other groups march along Mohammed V Avenue proclaiming their frustration through loud hailers.

There is no Tahrir Square here, no daily focal point to the protests. But the democratic wave that swept Egypt and Tunisia has emboldened many Moroccans to make unprecedented calls for reform.

"They dare to voice criticism that they haven't dared to before; they dare say we want a king who does not rule, but who is a symbol. They dare to say and discuss this. Before it was not permitted," says Mohamed El-Boukili, of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights.

Restrictions on speech

He points out that King Mohammed VI was greeted as a reformer following the abusive reign of his father, King Hassan II, who ruled through torture, killing and forced disappearances.

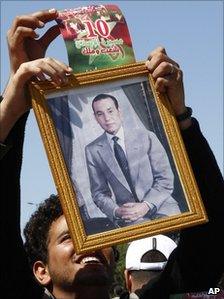

Many Moroccans hold their king in high regard

Even so, restrictions on free speech remain: Several newspapers have been closed down, and the king remains unquestionable as Morocco's supreme religious authority as well as monarch.

"There are many civil society actors now creating pressure for change and real reform. There is real demand," says journalist Driss Ksikes. He received a three-year suspended sentence in 2007 for publishing jokes on politics, religion and sex.

"There is disequilibrium now. The monarchy is very strong, and the pressure from the streets for a free Morocco is very important. We know there is an opportunity and maybe there will not be another one," he adds.

So on the top floor of a trade union building in Rabat, the 20 February movement has been plotting their next move.

They have rejected a call to discuss the constitutional changes with the king's committee arguing that would lend legitimacy to a flawed process. Instead there is talk of sit-ins and flash mobs as well as the rally this weekend.

The hope is the movement can harness the frustration of other groups demonstrating for more specific needs - like jobs - and against a culture of corruption.

University graduates formed just one of the crowds marching past parliament last week, angry that their degrees get them nothing without connections or money.

"After events in the Arab world we took the chance to claim our rights too," says Ali, an unemployed English graduate on the march.

"We are suffering, and we could not say that before Tunisia and Egypt. But maybe we have more rights now."

"We're here to protest about many problems, including political ones. But the first is jobs," agreed Lahsin, an out-of-work teacher.

'The king listens'

There are now open calls for the King Mohammed's executive role to be reduced. But after three centuries of monarchy most Moroccans remain loyal to the institution.

Journalist Driss Ksikes received a three-year suspended sentence for publishing jokes

Many blame the government or palace advisers for their woes, not the king.

Their demands are for real reform, not revolution.

"What happened in Tunisia won't happen here, because the people love their king," says a man called Driss, sheltering from the sun in a run-down district of the capital.

"He is the only person actually doing things. When people protest, the king listens."

But the scale and scope of these protests are new for Morocco. Mindful of events elsewhere in North Africa, the state is scrambling to respond.

"Everyone is trying to answer young Moroccans great demands for deep change," believes Mr El-Boukili.

He has photographs showing how demonstrators were beaten on 20 February, but says the police have kept a conspicuously low profile ever since.

"People don't want slight changes any more. That will not calm the Moroccans. I hope they will understand this and give the answers the young expect," he says.

"There is a margin of freedoms now which was given under pressure. I hope it will give way to real democracy here in Morocco."

- Published10 March 2011

- Published9 March 2011

- Published22 February 2011

- Published20 February 2011