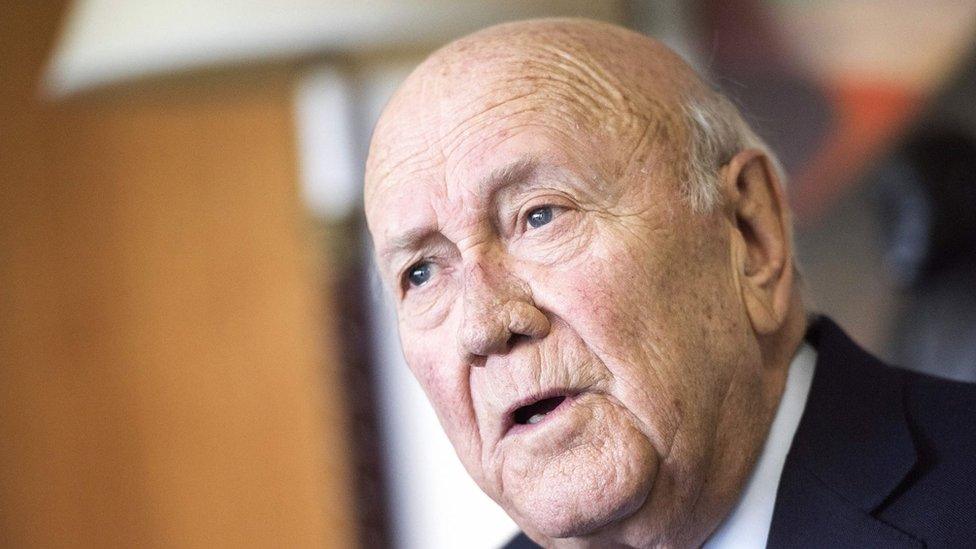

FW de Klerk: South Africa's last white president

- Published

FW de Klerk was a major force in South Africa's transition from racist state to fully fledged democracy.

While the tide of history would probably have made the change inevitable, it was De Klerk who accelerated the pace of reform.

Essentially a conservative by nature, the last president of a segregated nation came to believe that white-minority rule was not sustainable.

His ending of the ban on the African National Congress and freeing of Nelson Mandela were the steps that triggered the move to majority rule.

Frederik Willem de Klerk was born on 18 March 1936 in Johannesburg, into a line of Afrikaner National Party politicians. His father, Jan, had been a cabinet minister.

He went to Potchefstroom University, known for its conservatism, and by the time he took his law degree, apartheid was firmly established. After 11 years as a lawyer in 1972 he won a safe parliamentary seat for the National Party, which had introduced the system of apartheid in 1948.

A series of ministerial posts, the last in education, took him to the top of his party. At the time he was a firm believer in apartheid and its legal architecture: separate residential areas, schools and institutions for different race groups.

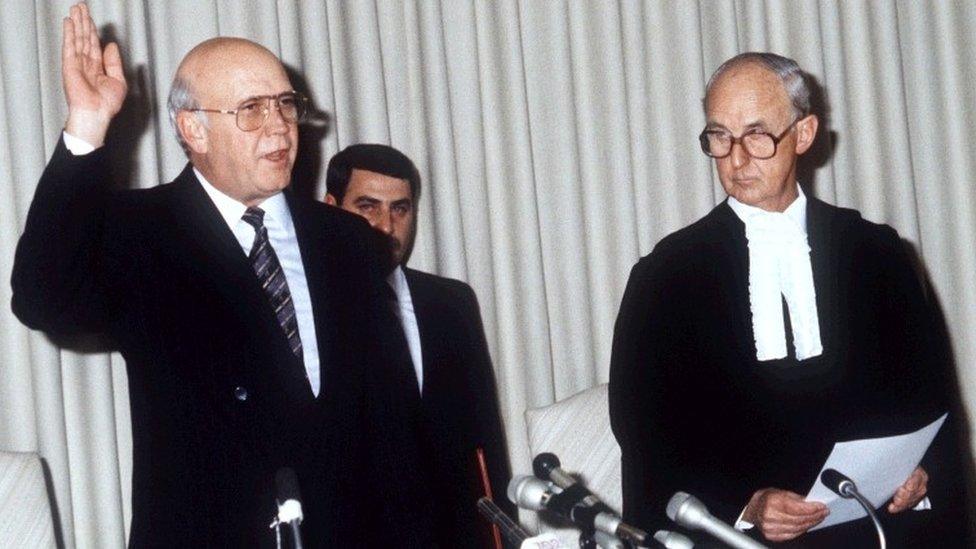

He became state president in 1989

Nevertheless, De Klerk was a relative outsider when he became party leader in February 1989, after President PW Botha suffered a stroke.

Six months later, after a bitter row with Botha, he took over as president.

The arch-conservative Botha had often spoken of the need for reform, but he had resisted calls for the removal of the ban on anti-apartheid groups, and his government had responded with force to the protests that engulfed the country in the late 1980s.

Old wounds

After just a few months in power, De Klerk demonstrated that he was prepared to tread where Botha had never dared. He publicly called for a non-racist South Africa and late in 1989 he freed top African National Congress (ANC) official Walter Sisulu and other political prisoners as a preliminary move ahead of his more sweeping reforms.

On 2 February 1990, President De Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC and released Nelson Mandela nine days later.

It must have been apparent to De Klerk, as he watched Mandela walk to freedom, that his own days in power were numbered.

The remainder of his term in office was dominated by the negotiations that were to eventually lead to majority rule.

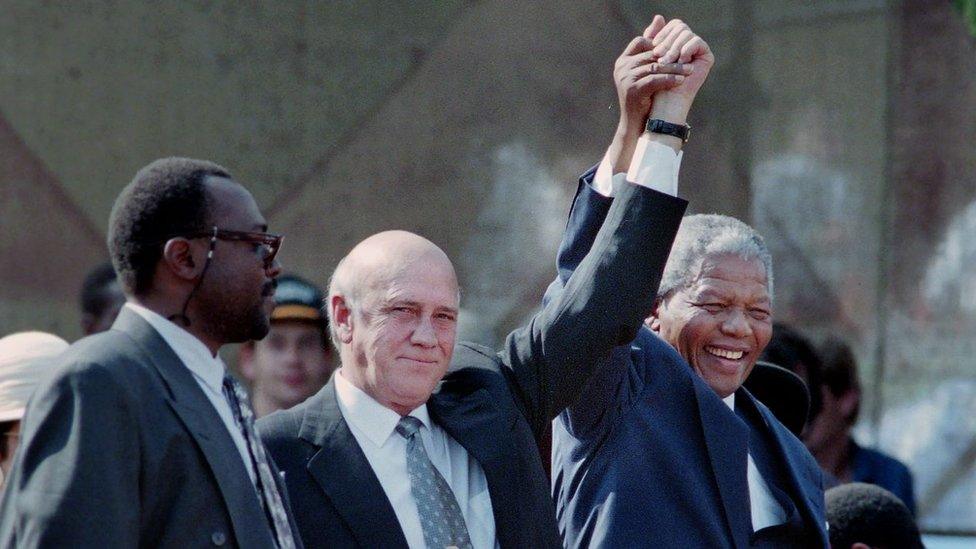

FW de Klerk and Nelson Mandela shared the 1993 Nobel Peace prize

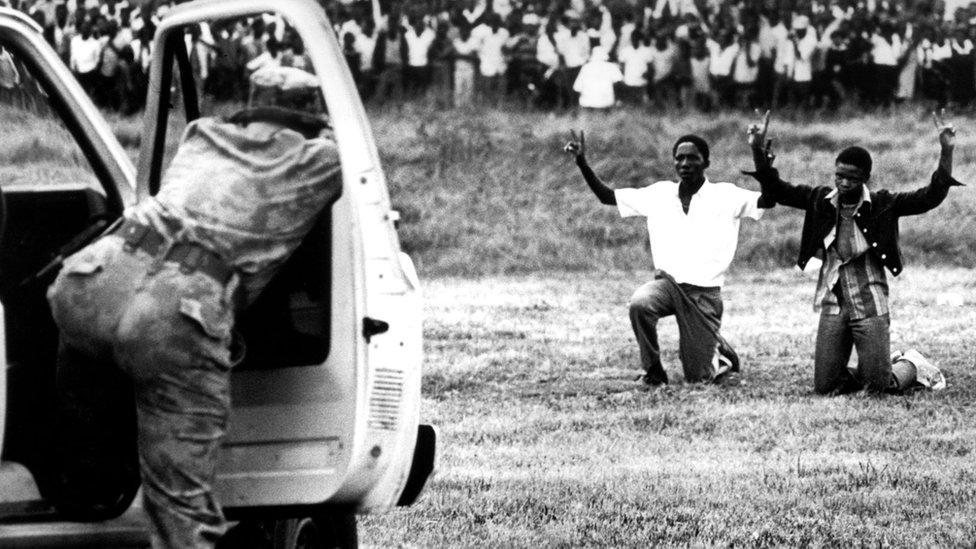

But talks about a new constitution opened old wounds. There was appalling violence between the ANC and its rivals in the Inkatha Freedom Party.

In April, De Klerk announced that security forces would be sent back into the townships. He stressed his government's desire to "finally close the old books and start on a clean page".

Those clinging to the armed struggle and insisting on continued domination "must realise that we are deadly serious about building the new South Africa without brutality and without unrest. Violence and armed struggle are misplaced".

Mandela's authorised biographer, the journalist Anthony Sampson, later suggested that De Klerk had connived with the security forces in an attempt to split the two main anti-apartheid factions. It was an accusation Mandela himself made in his book, Long Walk to Freedom.

"Despite his seemingly progressive actions, Mr. de Klerk was by no means the great emancipator," Mandela wrote. "He did not make any of his reforms with the intention of putting himself out of power. He made them for precisely the opposite reason: to ensure power for the Afrikaner in a new dispensation."

Pace of change

Sampson also alleged De Klerk allowed ministers to secretly support pro-apartheid organisations which collectively became known as the Third Force.

Anti-apartheid protests were brutally suppressed in the 1970s and 80s

De Klerk strongly denied the allegations, saying he had no power over those taking violent actions against the move to democracy but later admitted in a 2004 interview that security forces had conducted undercover activities. He also accused the ANC of harbouring extremist elements intent on disrupting the peace process.

Also agitated were white extremists - upset at the prospect of a black government. De Klerk sensed the threat and outmanoeuvred them by offering a "whites only" referendum in 1992, in which a majority of white voters endorsed further reform.

The pace of change now seemed unstoppable and world attitudes to South Africa were changing. In 1993, De Klerk was jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize with Nelson Mandela, the man who would replace him as president.

He served as deputy president after the first all-race vote in 1994 and retired from politics in 1997 saying: "I am resigning because I am convinced it is in the best interest of the party and the country."

Although the relationship between De Klerk and Mandela was often punctuated by bitter disagreements, the new president described the man he succeeded as someone of great integrity.

'Number of imperfections'

In 1998, De Klerk and his wife Marike divorced after 38 years when he was discovered to be having an affair with Elita Georgiades, the wife of a shipping tycoon, whom he later married.

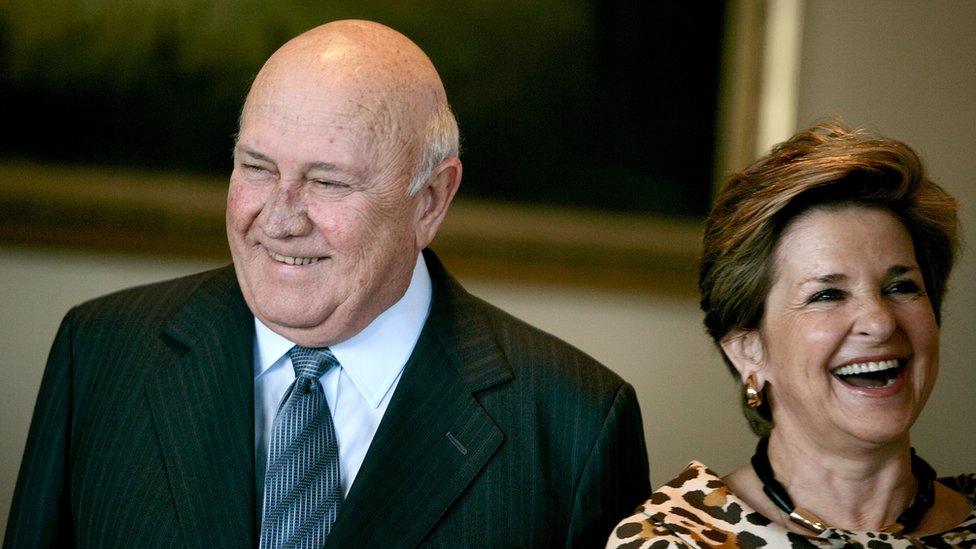

With his wife Elita in 2009

His actions were strongly condemned by Calvinist Afrikaners, one of the more conservative sections of white South African society.

Three years later, Marike was murdered during the course of a robbery. A 21-year-old security guard was later convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for the killing.

De Klerk did not abandon politics. He founded the FW de Klerk Foundation to promote peaceful activities in multi-community countries and travelled the world as an advocate for democracy.

In 2004 he quit the New National Party because of a planned merger with the ANC. He professed himself broadly satisfied with the changes in South Africa but admitted there were "a number of imperfections".

When Nelson Mandela died in 2013, De Klerk paid tribute to the country's first black president. "He was a great unifier and a very, very special man in this regard, beyond everything else he did. This emphasis on reconciliation was his biggest legacy."

In 2015 he waded into the row at Oxford University, criticising the demand of activists that a statue of Cecil Rhodes at Oriel College should be removed. "Students," he said, "have always been full of sound and fury signifying nothing."

FW de Klerk remained loyal to his Afrikaner heritage. Some former colleagues complained he'd been opportunistic, simply seizing a moment because he saw the inevitability of change.

But, whatever his motives, his role in the relatively peaceful transition to majority rule in South Africa assures his place in the history books of the 20th Century.