What now for Colonel Gaddafi's Green Book?

- Published

Study of the Green Book was compulsory for young Libyans

In the history of political thought, the Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi's Green Book will probably go down as one of the most bizarre sets of governing principles ever written. Now, for the first time, some Libyans are free to say what they really think of the text that has loomed so large in their lives for more than three decades, as the BBC's John Sudworth reports.

The small 82-page book is part Chairman Mao and part Marx and Engels.

Mostly, though, it's a glimpse into the mind of the man who has ruled Libya since 1969 and is now fighting to stay in power.

In it, Colonel Gaddafi waxes lyrical on subjects as diverse as democracy, tribalism, the tenderness of women and the inhumanity of the sport of boxing.

He rages against liberal democracy and capitalism, proposing instead his Third Universal Theory, a system of people's committees.

The book, Col Gaddafi once said, "had resolved man's problems", but in practice, of course, his political system has proved to be very much pyramid shaped, with him at the top.

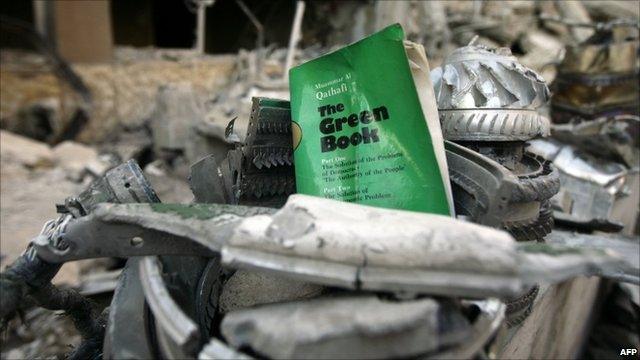

Here in the eastern city of Benghazi, now under rebel control, one of the first buildings to be attacked during the uprising two months ago, was the Centre for Recitation and Study of the Green Book.

It is now burnt and broken, and on the pavement outside is a pile of ashes, the remains of so many Green Books that the protesters brought along as fuel for their bonfire.

Mohammed Ramadan is an engineering student at Benghazi's Garyounis University.

Like all young Libyans, study of the Green Book was, until two months ago, a compulsory and constant aspect of his academic life.

"I had to study it from grade one until now, and I've almost finished university," he tells me.

"So you can imagine how many years, how many hours in my life I spent in lessons explaining what the Green Book is about."

Rambling text

The book, most impartial readers would surely agree, is rambling, contradictory and often simply bizarre.

Col Gadaffi even finds time to discuss the evils of sports clubs, dismissed as "rapacious social instruments".

The book sets out Col Gadaffi's political philosophy

So what about the teachers who took part in what is surely one of the most pointless academic exercises the world has ever seen?

What do they think now?

I met one man who spent his time before the Libyan revolution teaching the Green Book to university students.

In his biggest class, 300 had to sit through his lectures.

Perhaps, there was the odd raised eyebrow amongst his audience when exploring the colonel's insights into the subject of the difference between the sexes.

"According to gynaecologists, women, unlike men, menstruate each month," he tells his readers.

The lecturer is reluctant to give me his name; these are of course still uncertain times in Benghazi.

"For me, I needed the money. There were no jobs for me as a political scientist, other than teaching the Green Book," he says.

"In addition, it was the only way for me to advance my career, to get a scholarship to go abroad, for example."

I ask him what would have happened if he had stood up in class one day and told his students that the book was rubbish.

Copies of the Green Book were symbolically burned at the start of the uprising

"One word," he replies, "execution."

There were, of course, those who did challenge Col Gaddafi's rule and served time in jail, or worse, for doing so.

"I don't feel guilty," the teacher says, "just so sad because I had to do it, under pressure."

And what of the book itself? Now that he is free to talk, how would he sum up what value, what knowledge, there is to be gleaned from those 82 pages?

"Zero," he says.

The Green Book is not the worst aspect of Gadaffi's rule of course.

The rambling text forced on students for so many years appears almost comical when weighed alongside his feared interior police, the political prisoners and the extra judicial killings.

But it gives an important glimpse into the resilience of authoritarian regimes the world over.

Here in Benghazi, long after people had lost faith in their leader, and his book, it was still being taught by teachers who didn't believe in it, to students who didn't want to read it.