The politics of human rights in Ivory Coast

- Published

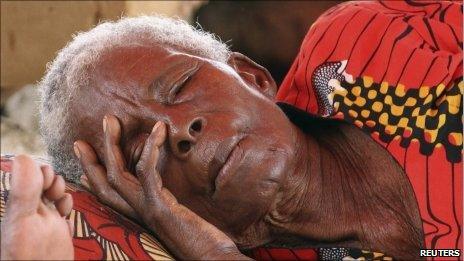

This woman is one of thousands still sheltering in a church compound

An Amnesty International report on Ivory Coast has said both sides in the country's recent political and military crisis committed war crimes.

But as well as cataloguing human rights violations during the six months since last November's disputed elections, the report is a reminder of the direct links, external between the worlds of human rights and politics.

Amnesty details massacres committed by forces loyal to the current President, Alassane Ouattara, and calls for an end to a decade of impunity.

But the decisions that would have to be made to end that impunity would be intensely political.

They would involve probing the roles played by some of the armed men who ultimately brought President Ouattara to power after his electoral victory was denied to him by Laurent Gbagbo refusing to leave office - men who also stand accused of responsibility for massacres.

This is where the worlds of human rights and high politics collide.

The report also accuses the forces loyal to former President Gbagbo of committing war crimes, including the shelling of civilian neighbourhoods.

On one notorious occasion, a group of woman who were demonstrating against Mr Gbagbo clinging to power - despite most of the world saying he had lost the elections - were fired on by troops loyal to him.

"They suddenly opened fire on us," one eyewitness told Amnesty researchers.

"Six women and a baby who was with her mother were killed immediately. Several people were wounded."

But if Mr Gbagbo can be accused of taking command responsibility for the actions of his supporters, so can the other side.

Duekoue massacres

In March of this year, prior to Mr Gbagbo's arrest, Mr Ouattara merged the military forces that supported him into a new army under his command, the Republican Forces of Ivory Coast (FRCI).

The leader of many of the men who joined the FRCI was Mr Ouattara's Prime Minister, Guillaume Soro.

So from the moment the formation of the FRCI was announced in a speech by Mr Ouattara on 8 March, there was a direct line of command - or, at least, a direct line of responsibility - from Mr Ouattara, through Mr Soro, to the armed forces that overthrew Mr Gbagbo.

Some of the worst human rights abuses committed by the FRCI and its allies occurred after 8 March.

According to detailed testimony in the Amnesty report, hundreds of men were systematically killed in western Ivory Coast by the FRCI and its militias in a campaign that started on 28 March.

The killings took place in an ethnically mixed area in and around the town of Duekoue.

The people in this part of Ivory Coast have been manipulated by politicians into forming two broad groups: the "indigenous" people who are mainly from the Guere ethnic group; and the "non-indigenous", who are from the north of Ivory Coast or from neighbouring northern countries.

This last group are commonly called "dioulas", but are in fact a mixture of ethnic groups. Although they are labelled as incomers, many have been settled there for several generations.

The "indigenous" group tended to support Mr Gbagbo and the "non-indigenous" were taken to support Mr Ouattara (although in practice of course, were it not for the power struggle in Abidjan, most people of both groups would happily ignore politics and get on with their lives).

The FRCI fighters targeted the Guere.

One woman in Duekoue said of the FRCI and their militia allies, known as Dozos:

"They came into the yard and chased the women away. Then they told the men to line up and asked them to state their first and second names and show their identity cards. Then they executed them."

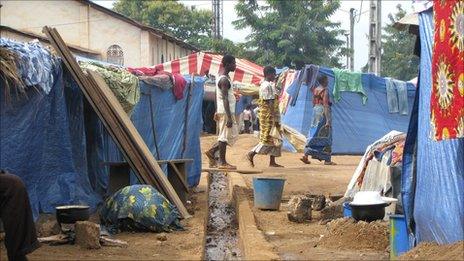

Many ethnic Gueres are still living in camps in Duekoue

'No impunity'

President Ouattara said in a recent interview in Abidjan with the BBC's Barbara Plett that there will be "no impunity".

When asked how far he was willing to go in prosecuting his own supporters, Mr Ouattara said:

"I think the courts will do their job. First, we have to investigate. I've sent the prosecutor to conduct a national investigation, and we've asked the United Nations Human Rights Commission to come and make an investigation... if they say specific persons have committed crimes, they will be judged like anyone else."

But when pressed in the interview that some of the people who committed atrocities had been under the command of his own prime minister for eight years, Mr Ouattara said:

"No, no... Let's be clear that the prime minister has nothing to do with this. These were crimes allegedly committed in specific areas at specific times, so the prime minister has nothing to do with this."

It appears this is where President Ouattara has decided to draw the line between human rights and politics.

Although there has not been a full public investigation that might point to Mr Ouattara or Mr Soro having command responsibility for atrocities, it seems the president has already ruled out any responsibility at this level.

Where the line is drawn between human rights and politics is crucial for Ivory Coast because the country has never had a rigorous system of justice that could end impunity and begin to entrench democracy.

Ivorian 'amnesia'

The Amnesty report speaks to a long period of "amnesia" in Ivory Coast during which "successive governments have deliberately refused to accept their responsibility to fight impunity".

The situation in Duekoue could become another example of that amnesia because the outbreak of violence there symbolises a wider debate in Ivory Coast over national identity.

At least a third of the population of the country hails from neighbouring states such as Mali and Burkina Faso. These foreign nationals are mainly Muslims, as are the majority of the people in northern Ivory Coast - and as is President Ouattara.

For many years, the southern political establishment has sought to exclude Mr Ouattara from power by promoting a nationalist policy of Ivoirite or "Ivorian-ness".

This policy, which sometimes borders on xenophobia, is interpreted on the streets of southern Ivory Coast as pro-southerner, anti-northerner, anti-foreigner - and anti-Ouattara.

If President Ouattara, a northerner, is seen to be trying to hide any aspect of the crimes committed in the Duekoue area, it could store up political trouble for the future.

A well-informed observer of Ivorian politics in Abidjan described this situation in another way.

"Ivorian politicians have a long history of avoiding the real issues facing the country. And that's dangerous because sooner or later, these issues of Ivoirite and national identity could explode again."