Angola victory for cyber activists?

- Published

In a rare climbdown, the Angolan government has withdrawn controversial legislation severely restricting how people use the internet.

It was scrapped this week at the eleventh hour when the government removed it from parliament moments before it was due to be voted into law.

Under the proposal, which had already passed a first round of voting, it would have been illegal to share information electronically that could "destroy, alter or subvert state institutions" or "damage national integrity or independence".

This would have meant anyone criticising the government on social networking sites such as Facebook, or receiving an email containing anti-government sentiment, could have faced up to 12 years in prison.

The law also wanted to ban the online sharing of videos, pictures or recordings without the subject's consent, criminalise "whistle-blowing" under the crime of "espionage" and make it illegal for anyone to search for information about the state, even if it was not classified.

Minister of State Carlos Feijo told reporters in the capital, Luanda, that a decision had been made instead to insert special clauses about internet crimes into the new penal code currently under revision.

But many believe pressure from civil society and local journalists, who had strongly opposed the legislation claiming that it was "totalitarian" and violated basic freedom of expression, played a role in the decision to abandon the law.

US-based lobby group Human Rights Watch said, external the legislation would have "undercut both freedom of expression and information, and posed a severe threat to independent media, whistle-blowers, and investigative journalism".

With most of Angola's traditional media controlled by the state, or owned by government ministers and their business associates, there is little free debate in the newspapers or on television and radio.

Opposition parties are rarely afforded column inches or air time, while government and presidential activities are covered in minute detail and nearly always with a positive spin.

Civil society and opposition groups have therefore turned to the internet, even though only 1% of Angolans have access to the web, to hold their debates and share information through blogs and social networking sites.

'Insult'

In recent months, several anti-government marches have been organised and promoted through Facebook, where there are pages dedicated to opposing the president of nearly 32 years, Jose Eduardo dos Santos. There, people make comments they would not dare speak out loud in public.

More than 15 people were detained during this week's protest

Angolans living in the diaspora have also been busy online, creating websites to rally support for regime change, and there have been several solidarity protest events held in South Africa, the UK and Belgium.

Many are growing weary of the current regime and want more to be done to share the country's oil wealth among the majority, two thirds of whom still live in poverty and many without access to water or electricity.

The introduction of a special internet law was seen as a deliberate attempt to quash the online discussion that was fuelling this unrest.

In an uncharacteristically emotional speech last month, President dos Santos lashed out at social media sites, saying they were being used to "insult, denigrate and provoke uproar and confusion".

Officially the government stuck to its position that the technology legislation was needed to curb crimes such as child pornography, hacking and online financial fraud.

The editor of the private weekly newspaper Angolense, Suzana Mendes, who was among the journalists who publicly voiced concerns about the law, welcomed its withdrawal.

"The fact that the bill has been cancelled is important, because if it had been approved, it would have endangered our fundamental rights to inform and be informed," she told the BBC.

Sizaltina Cutaia, from the Angolan office of the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (Osisa), which also opposed the bill, said they were pleased the government had backed down.

"This is definitely a victory for us and it is encouraging that we were able to get our message across." she said.

Small numbers

However, civil society celebrations around the scrapping of the legislation were short-lived after a number of activists were arrested on Wednesday for taking part in an anti-poverty demonstration in Luanda.

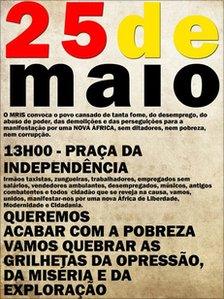

Organised via Facebook by a group calling itself the Revolutionary Movement of Social Intervention (MRIS), the protest was due to take place at lunchtime.

But following the arrest of MRIS leader Luis Bernardo, allegedly detained while putting up posters near his home in the district of Cazenga, only a few dozen people gathered in the city square.

According to reports, between 15 and 20 people were detained, among them a journalist and a representative from Osisa who had been trying to film the arrests.

They were later released and rejoined the protest, which at its height numbered around 100 people.

A spokesman for Luanda's provincial government told state media that the youth involved, who claimed they had authorisation to stage the protest, had acted "criminally" and the police force was within its rights to respond.

"What the government needs to realise is that the more they repress people, the more they will want to demonstrate," Ms Cutaia said.

Although small in size and number, protests like these are a relatively new phenomenon in Angola where few have dared to question the authority of President Dos Santos and his ruling MPLA.

"The people leading these protests are young and they don't have as much to lose. They were born after independence so they don't have that connection to the ruling party like older generations," Ms Cutaia says.

"All they see is that despite Angola's wealth under the MPLA most people have remained poor and they want that to change.

"Most of all they want the right to be able to make their voices heard."