Meeting the Algerian guerrilla leader who fought France

- Published

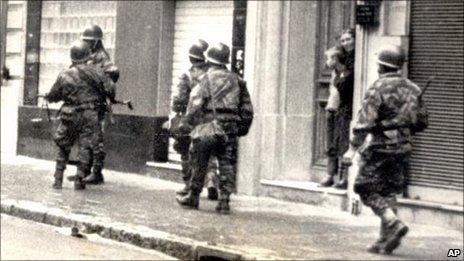

Algerians waged a brutal war against French forces to achieve independence

Sometime after the 9/11 attacks on New York, two Americans went to the Algerian capital, Algiers, on a secret mission.

For centuries, the city has been a place of grim fascination for outsiders.

The raising of the US Navy as a permanent full-time force was a response to the depredations of the Barbary Corsairs - the pirate force which based itself in the Muslim ports of the Maghreb and preyed on Western shipping.

The Casbah of Algiers - a steep and twisting warren of white stone buildings that spills down to the Mediterranean shore like a heap of dirty sugar-cubes - had been one of their strongest redoubts.

And 20 years ago, Algeria was gripped by a vicious civil war which may have killed as many as 200,000 people.

The conflict was triggered when the military-backed government scrapped an election in the early 1990s after the first-round results suggested that Islamists were on the point of winning.

But these Americans were interested in a third, equally dark and bitter period of Algerian history - the struggle for liberation from French colonialism in the 1950s and 1960s.

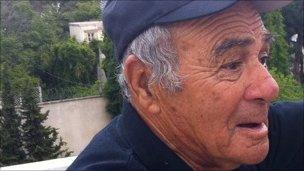

The Algerian guerrilla leader Yacef Saadi masterminded the war against French forces

They had come to seek out Yacef Saadi, the Algerian guerrilla leader whose memoirs of the independence war formed the basis of the film, La Bataille d'Algers (The Battle of Algiers), which remains one of the most compelling studies of insurrection and counter-insurgency ever recorded.

I made the same journey as the two US intelligence officers up the steep hills to the south of Algiers to find the spacious villa where Mr Saadi now lives, commanding a stunning view of the city he helped turn into a battleground to free his country.

It is possible that I had a more fruitful visit than the Americans.

When Mr Saadi realised from the nature of their questions that they were intelligence officials trying to gather information that might help the United States in its newly-launched war in Iraq, he had some blunt advice for them.

"Listen," he said. "The day you land in Iraq is the day you lose the war there."

Vietnam

He was not surprised that the Americans had sought him out.

It has long been said that the Pentagon uses The Battle of Algiers as a training aid, encouraging young officers to watch it.

In part, this is presumably because some of the observations about an army from a Western, Christian country fighting a Muslim, Arab insurrection are still valid.

It is also a salutary reminder of how hard an indigenous guerrilla force will fight against a foreign invader.

Mr Saadi makes the point that the Americans could have learned that story in Vietnam but he acknowledges that it is there in his own life-story too.

But partly the film's enduring power comes simply from the fact that it was a brilliant piece of story-telling, its grainy monochrome texture lending a newsreel authenticity and a dark urgency.

It is something of a miracle that it turned out to offer such a subtle narrative of intertwined stories and perspectives.

An early plan for the project was called Para! and would have told the story from the French point of view.

And the finished product is based on the memoirs of a man the French would have regarded as a ruthless terrorist.

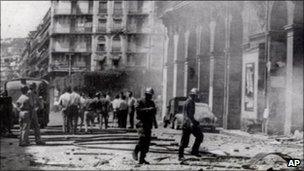

The US hoped to learn the lessons from Algeria before it went into Iraq

Even though he had been invited to make the film by the authorities in newly-independent Algeria, the Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo somehow managed to stick to his plan to reflect the parallel narratives which between them provide the full story of the war.

The French tortured prisoners, staged brutal reprisal raids and deployed paratroopers in the Casbah to bully the local civilian population into submission.

The Algerians used no-warning bomb attacks and were ruthless in hunting down agents of the French government - and anyone suspected of collaborating with them - when they were at their most defenceless.

There is one sequence in which three Algerian Muslim women remove their robes and headscarves and dress in European clothes to allow them to slip through French security and plant no-warning bombs in civilian area, including an airline office and a cafe.

The slow passage of time, as the minutes tick by towards detonation while young people in the cafe dance to a song called "See You Tomorrow," must be among the most tense moments in the movie.

For many of the dancers, you know, there will be no tomorrow.

I stood with Mr Saadi on his balcony looking over the dirty white stone city to the sharp blue of the Mediterranean.

Algerians did not give warning of their attacks

"There were battles everywhere," he told me. "Attacks even in the sleepiest suburbs, first to take their weapons and then to fight them."

I asked him, as I often ask old soldiers, if the darker memories of those violent days ever haunt his dreams. He gave me the shortest answer I have ever heard.

"Of course not," he said. 'Victory was ours."

I wondered what those two American visitors had made of the man whose life story has become a kind of handbook for how a small, irregular army with the right motivation can fight and beat a much larger and better-armed force.

"They didn't need to come to see me to ask that," he told me. "All you need to know to understand that is that we won our freedom."

- Published2 June 2011

- Published11 January 2011

- Published16 April 2011