Swaziland: A kingdom in crisis

- Published

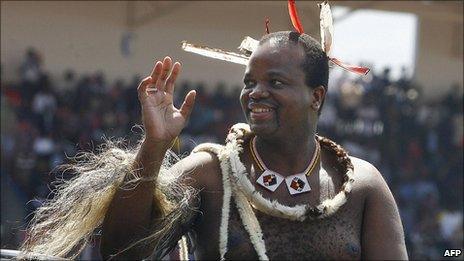

Swaziland's King Mswati III ascended to the throne 25 years ago but he has little to celebrate during his silver jubilee.

An absolute monarch who rules over 1.2 million people, his government is in financial ruin, running out of cash for salaries, health care and fuel.

"My wife works at the university. Last month they got paid late. And they don't know what will happen when it's pay day again," Sikelela Dlamini, the co-ordinator of the opposition Swaziland United Democratic Front (SUDF), told the BBC.

"In the health sector, it's worse. Some people got only half their salaries. There is no money - only panic," he says.

The crisis has been caused by profligate spending - on the royal family of 13 wives, as well as unbudgeted wage increases - and a sharp decline in income because of the global economic crisis and new trade rules in the region, analysts say.

Patient care is at risk, in a country with one of the world's highest rates of HIV/Aids infection.

According to a report in the privately owned Times of Swaziland newspaper, MP Joseph Madonsela told parliament recently that state hospitals would run out of anti-retroviral drugs within two months.

This was disputed by Health Minister Benedict Xaba.

"The two months stock that is reported to be left is just a buffer stock. Otherwise, we have reserve stock when the drugs are needed," he said.

The future of cancer patients is also bleak.

The tiny kingdom's hospitals have always been badly resourced - and it financed the treatment of some 300 cancer patients in neighbouring South Africa.

But this has now stopped, and patients have been brought back to Swaziland.

"Unfortunately, we do not have the chemotherapy equipment to truly treat these patients," says Timothy Vilakati of the Cancer Association of Swaziland.

'Generation of orphans'

Mr Dlamini says the government - which did not respond to BBC requests for an an interview - is facing a cash-flow crisis on other fronts as well.

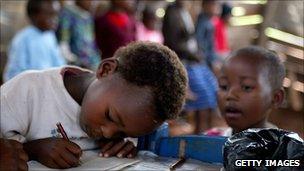

Education is free for some Swazi children

"You will see cars parked. There is no fuel; no money," he says.

An analyst with South Africa's Institute for International Affairs, Catherine Grant-Makokera, points out that companies which supply the government with goods and services are not being paid either.

"Even printers haven't been paid," she says.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which sent a team to Swaziland in May to assess the situation, says Swaziland faces a "serious liquidity crisis", and needs to curb expenditure.

There appears to be agreement among all Swazis on the need for cuts, but they disagree on what should be targeted.

Under the headline "Economic crisis", The Times of Swaziland ran a poll last month, external, asking readers whether the government should continue to spend on anti-retrovirals, free education or fuel.

The majority voted for fuel (51%), followed by anti-retrovirals (36%) and free education (13%).

Commenting on the poll, the chairman of the Swaziland Aids Support Organisation (Saso), Hannie Dlamini is not surprised by the importance placed on fuel.

"You need fuel to get things done, but the problem is that officials are wasting it. They use fuel to run errands - not to go to rural areas to serve communities.

"This government is not doing things right. There is a lot of corruption and wastage," he says.

He argues that Swaziland cannot afford to reduce spending on either anti-retrovirals (230,000 people are HIV-positive, of whom 65,000 are getting drugs) or free education.

"We have a generation of orphans [because of HIV/Aids]. Fifteen year olds are responsible for homes. The extended family system is breaking down and there is no-one to look after orphans.

"So, the government cannot reduce spending on anti-retrovirals. But free education is also important. The problem is that there was no proper planning when free education [for school beginners] was introduced a few years ago," Saso's Mr Dlamini says.

Ms Grant-Makokera says the financial crisis has been triggered by a sharp decline in the landlocked kingdom's income from the Southern African Customs Union (Sacu), following a new tariff deal.

"Sacu has a complicated tariff formula, where they assess what trade flows are likely to be, what each country should get and what adjustments should be made.

"In the end, the revenue Swaziland received [mainly from trade with South Africa] was lower than expected.

"There was also the global economic crisis. So, Swaziland faced a double hit," she says.

'Savage cuts'

The IMF also cited a 4.5% unbudgeted wage increase for civil servants and politicians last year, as well as overspending on "goods and services - notably defence", as other reasons for the financial hole.

Mr Dlamini of the opposition SUDF believes the military should face savage cuts, as it consumes nearly a fifth of the national budget of about $1.6bn [£1bn].

"Swaziland is not going to fight a war anytime soon so why this expenditure? It is typical of a dictatorship," he says.

The government has announced a wage freeze in the civil service to curb over-spending, prompting widespread protests from trade unions.

For Ms Grant-Makokera, there is no doubt that the civil service needs to be trimmed.

"Swaziland has to take a long, hard look at its fiscal expenditure. It has one of the biggest civil services in the world, in relative terms," she says.

Disagreeing, Mr Dlamini argues that Swaziland cannot risk job losses as it is already battling high unemployment.

Instead, he believes Swaziland should stop funding government ministries that promote the king's rule, as well as the royal family.

"The king has 13 wives, many children and many more servants. They take a huge chunk of the budget," Mr Dlamini says.

Ms Grant-Makokera believes the monarch may have hindered the government's efforts to resolve the financial crisis.

Critics say the 13 queens lead a lavish lifestyle

"I've got respect for the Swazi prime minister. Maybe, he didn't have the ability to implement tough decisions because of the rule of the monarch.

"But there now seems to be an acknowledgement [by the king] of the need to make adjustments. He has cancelled his silver jubilee celebrations," Ms Grant-Makokera says.

Swaziland has also asked South Africa for a reported bailout of about $1.4m after the African Development Bank turned down its plea for help.

"The expectation of Swaziland is that South Africa is going to help - that you are big brother and you are going to bail us out," says Ms Grant-Makokera.

South African officials have hinted that they will agree to the request because with another neighbour - Zimbabwe - in economic crisis, Pretoria cannot risk Swaziland's collapse.

Mr Dlamini says aid should be given on condition Swaziland accepts democracy.

"Otherwise, it doesn't make sense. The king believes power inherently belongs to him, and there are no real checks and balances. That is why we have this crisis," says Mr Dlamini.

But with the security forces ruthlessly stamping out any political activity, the king shows no sign of relaxing the ban on political parties.

- Published30 June 2011

- Published22 June 2011

- Published12 April 2011

- Published18 March 2011

- Published10 September 2010