Horn of Africa drought: Survival of the fittest

- Published

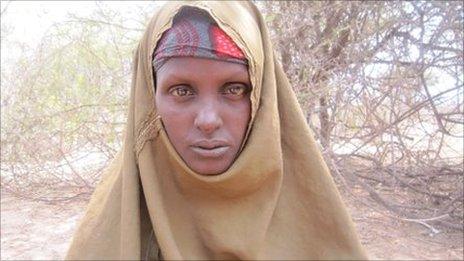

Weheleey Osman Haji gave birth after trekking for 22 days, still far from help

"It's a matter of life and death," says Weheleey Osman Haji, a day after giving birth near the Kenyan border town of Liboi.

She and her five other children arrived in Kenya after trekking for several weeks from their homeland in Somalia, whose ongoing conflict has left it the country least able to cope with the Horn of Africa's worst drought in 60 years.

The 33 year old has named her new baby Iisha, which loosely translates as "life".

Deep asleep in his mother's arms during the BBC interview, he was unaware of the circumstances under which he came into this world.

The one day old was born under an acacia tree 80km (50 miles) north of Kenya's Dadaab refugee camp, where thousands of Somalis are heading every day after arduous journeys.

They cross the border expecting immediate respite, but many of the refugees are unaware of the long distance they still have to go to reach Dadaab.

"There was drought; We have been walking for 22 days drinking only water," Mrs Haji says.

"Since I delivered, I haven't eaten a thing.

"I now need food, life, water and shelter - everything that a human being needs."

'Nothing for the children'

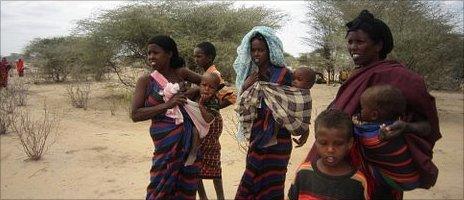

There are many mothers like Mrs Haji.

One-day-old Iisha's name loosely translates as "life"

One of them said how she left her sick child on the road because he was too weak to make the journey to Kenya.

Burdened by other small children, she left him in the desert.

"His eyes still haunt me to this day," she told us.

Rukiyo Maalim Noor too has been travelling for the past 20 days. She has a one-month-old baby.

"We just took off. We could not stay because of the drought. There was no food, nothing to give to the children,'' she said.

Some of the fleeing Somalis enter Kenya via the border town of Liboi, but most wander through the arid landscape towards Dadaab concerned that they will be turned away by Kenyan border officials.

The border between Kenya and Somalia was officially closed in early 2008 because of the conflict in Somalia, where Islamist militants have now taken control of most central and southern areas.

The journey from Liboi to Dadaab can take some people up to four days

The Kenyan authorities have feared that militias may cross the long and porous border.

However, the acting District Commissioner of Dadaab, Bernard Ole Kipury, says that Kenya is a signatory to international treaties and cannot turn away people who need help.

Smugglers

The challenge for the Kenyans is to track those who are off the road in the bush, sometimes unsure of the way to the camp.

Local leaders believe that smuggling cartels within Somalia are also exploiting the refugees, by promising to deliver them into the Kenyan camps if they pay a fee.

But the middlemen often abandon them in the desert.

Earlier this week, the al-Shabab militant group announced that it had lifted its two-year-old ban on food aid, which may allow foreign aid agencies into the large swathes of territory it controls.

When we told Mohammed Abdi, who was walking his wife and children towards Dadaab about the lifting of the ban, he was sceptical.

"They [al-Shabab militiamen] stopped us on the way and told us to turn back," the farmer and herdsman said.

"They said it was better to die in our motherland. They wanted us to pray for the rains."

But Mr Abdi said had no choice but to leave and he set out on his journey on 18 June.

"Most of my family is in the bush also making the trek to the Dadaab refugee camp."

He said he knows other people who have already made it to the camp.

"It's ironic. There is relative peace in Somalia where I live. But we are still fleeing.

"It's because of the drought. We have lost everything now other than these two camels. There is no need to hang on.''

There are actually three camps at Dadaab, which are already overcrowded with more than 370,000 refugees - way more than the 90,000 capacity they were built for.

Aid organisations say they are over-stretched. It can take between seven and 12 days to get the first food rations to the camps.

A UN refugee agency spokesman told the BBC he hoped a transit camp could be set up at Liboi to give immediate relief to those crossing the border.

Some of those who reach Liboi are too weak to walk any further.

If they are lucky they manage to get lifts from vehicles plying the route, but many cannot afford to pay.

Mr Abdi said he used to be a wealthy man.

"It breaks me to see my children suffer. But what can I do? I have tried where I could."

He walked away from us, throwing up his hands in the air as if in submission.