Hunger and child begging test Uganda aid experiment

- Published

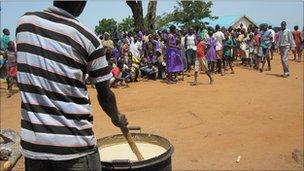

The people living in Karamoja are among the poorest in the world

As appeals continue for the drought in East Africa, aid agencies' eyes are on a region in nearby Uganda which is the focus of a global experiment in aid.

In the past year, the UN's World Food Programme has begun a project to try to end aid dependency in Karamoja and make the 1.2 million people there self-sufficient.

Food handouts are being strictly regulated, but many villagers are complaining of food shortages and charities report an increase in street begging by children.

"It's getting worse because now there's no food for the children, they all come back to Kampala to beg to earn a living," says Maureen Mwagale, who runs a small charity called Kaana, external.

"These children are both physically and mentally abused."

The children, as young as two, sit on the pavement of a busy shopping area, hands outstretched for money. We found two - Longorio, aged four, and his three-year-old cousin Lochien, being looked after by his 13-year-old sister, Nachiru Ellen.

She said she used to go to school but because of the lack of food in Karamoja her parents sent her to Kampala. Between the three of them, they had earned about $1 (£0.62) that day.

World's poorest

The children send much of the money to their village, Lorikitai.

Once there, we were told that up to 60 children from the community had been sent to Kampala to beg. Lochien's aunt, Napfu, said her own little boy was there, too, and her little daughter would go soon.

"There's nothing we can give them here," said Nachiru Ellen's father, Peter Lochoro.

The landscape of Karamoja is cruel and arid, the people among the poorest in the world.

The UN's experiment includes planting thousands of acres of robust crop like sorghum and cassava that can withstand drought, starting new businesses and bringing infrastructure and some economy to the area.

But even now, serious glitches have arisen. The UN has cut school meals because of what it describes as an administrative problem with the supply chain.

"We used to have breakfast, lunch and supper," says Diko Ben, the headmaster of Loodoi Primary School. "Now there's just a midday snack. Many here are now malnourished and if it stays like this, I don't think you will see a future."

Mr Ben says 200 children, a quarter of the whole school, have left because of the lack of food, adding that every child in school means one less under threat of being sent to beg in the cities.

The UN says meals will be restored by September and that, with the Ugandan government, it is drawing up a plan to end the crisis over Karamoja children. But it is not in place yet.

Children at the Loodoi Primary School only receive one meal a day now

One church charity rescues children - they are now at a boarding school in the town of Iriri.

"It was horrible," says Amei Mandy, now 10, who begged for five years. "At night people would come and beat me and take my money."

His friend Kodet Michael, also 10, says: "My mother said we had to go to Kampala because there was too much hunger. But when we got there she disappeared and left me."

Only about 20 children are at the school, while the UN estimates that more than 12,000 mothers and children from Karamoja are begging on Ugandan city streets.

Despite setbacks, the UN insists its experiment is on course. A year ago, $215m was spent on feeding people in Karamoja. This year that figure has been cut to $90m, the bulk of which goes not on food handouts but long-term development.

If this experiment does work, it will be rolled out in other parts of the world.