Solving Somalia's aid conundrum

- Published

- comments

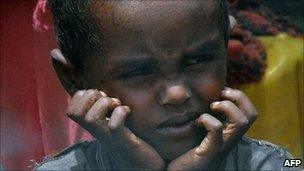

Local aid organisations are already working throughout Somalia

Mohammed Noor considers himself a lucky man.

I found him stretched out in the feeble shade of a dead tree surrounded by his three wives, and perhaps 20 children and neighbours.

The weary, hungry group arrived here, close to the border with Ethiopia, late last night after a relatively quick, four-day, 250km (155-mile) journey, by foot, car and donkey cart, from the central Somali town of Diinsoor.

"No-one died on the way," said Mohammed, a wiry 55 year old.

"We lost all our livestock to the drought, and we had lots of problems from al-Shabab. They are killing people, and taking food from them. They are enemies of our people and of the whole world. They are preventing aid from reaching our area. That's why we had to flee here.

"But I'm lucky. I had a little money to help us escape and to get food for the journey. We have nothing left now. But we are here."

The group is waiting - alongside a much larger crowd - to be registered by aid workers from the nearby town, and given food. Dolow is in one of several small pockets of territory controlled by Somalia's embattled, Western-backed government. By local standards, it is a relatively safe area - and as such a magnet for tens of thousands of families fleeing the famine.

But few people stay in Dolow. Instead they head across the border into the refugee camps in neighbouring Ethiopia. Mohammed says he intends to follow the crowds.

Cristalina Georgieva is hoping to stop him.

The European commissioner for humanitarian affairs is among a scrum of foreign dignitaries touring the drought zone right now. She has just announced a big increase in EU aid to the region. Now she has come to Dolow to work out how to spend it.

"Tell me what more you can do - and we will fund it," she announces to Dolow's local leaders in the dusty town centre. Smiles all round.

Commissioner Georgieva's plan is to try to push as much humanitarian aid as possible inside Somalia, so that families fleeing "don't have to cross into Ethiopia or Kenya and make refugee problems for the future".

"It's critical to identify communities that are friendly to IDPs [internally displaced people] and humanitarian workers and make sure help is there. I talk to people here and they tell me if there is a safe place inside Somalia where they can be helped then they'd rather be here."

'Loose umbrella'

There are dozens of experienced local aid organisations already working throughout Somalia - a fact that often gets lost in the furore over al-Shabab's hostile attitude towards some of the bigger international organisations, like the UN's World Food Programme.

The plan now is to try to use some of these local groups to funnel the vast sums of foreign aid money finally being promised into Somalia, taking the pressure off the swelling camps outside.

In areas like Dolow that may prove to be relatively straightforward, but the real struggle is to push aid - in the vast quantities now required - into regions controlled by al-Shabab.

"It's a dangerous environment… and time is not on our side," the EU commissioner concedes. "There are strongholds of al-Shabab where it is not possible today to reach out and help people.

"But it is categorically not true [that all al-Shabab areas are off limits]. We have learnt that in many villages nominally under al-Shabab control, local chiefs are asking for help and allowing humanitarian workers - mostly from organisations they already know - to come in and help."

There is no doubt that the drought - and the Arab spring - have shaken up the security situation in Somalia. Anecdotal evidence suggests al-Shabab is now seriously short of money, more divided than ever, and many of the foreign jihadist fighters who came to join it have left the country for other struggles.

The group is "nothing more than a loose umbrella - and a broke one", according to one well-informed source.

In some regions power has consequently shifted back towards local communities, potentially making them more likely to welcome foreign aid. But elsewhere, impoverished militia groups appear to be reverting to old ways - turning to banditry and extortion.

"Al-Shabab is like a dragon with many heads," said the EU commissioner. "Negotiating with one head doesn't mean you've received the blessing of the other.

"Our main danger today is that a substantial increase in funding may mean that less experienced organisations or individuals may rush in, out of the goodness of hearts, and may put their own lives and the lives of others in danger."

As for Mr Noor and his family, they still seem set on crossing the bridge and heading into Ethiopia.

"If the problem of al-Shabab goes away, and we have some assistance, then we can go back," he said. "But at home people are dying.

"I fear for those left behind - whatever livestock they have left will be taken from them, and it's likely they will die."