Residents' brief return to Fukushima exclusion zone

- Published

Residents of Fukushima had to don radiation suits to visit their former homes

The people gathered in a school gym on the edge of the Fukushima exclusion zone could not have imagined, only months ago, that they would need a radiation suit to visit their own homes.

They were being helped into the unfamiliar outfits by workers already wearing the white plastic overalls, overboots, masks and hats. The floors and the walls had been coated with pink plastic.

They were people who lived in the area around the reactors, still leaking radiation more than four months after they were crippled by Japan's earthquake and tsunami.

Now they are being allowed to go home, but only for a few hours, to look at the places they left behind.

Some had pet carriers, hoping to pick up animals they had to abandon - if they had survived. Others were hoping to collect documents, or treasured belongings.

Organisers called on them to line up in groups, depending on which village or town they wanted to get to. A dozen buses were going in today, carrying just a few of the 80,000 people who have had to evacuate.

Japan's government has promised everyone will have the opportunity.

Abandoned zone

They struggled on board, sweating in the heat and the plastic suits. Even the very old were keen to go and they were pushed in wheelchairs to the steps.

With the reactors still out of control who knew when they would get another chance?

The Fukushima exclusion zone is enforced by police roadblocks

The exclusion zone is enforced by police roadblocks, 20km (12 miles) from the plant. Beyond the countryside is empty. Homes are shuttered, traffic lights have been switched off. Plants are creeping into the road and colonising the pavements.

Outside a hospital, beds had been left strewn in the driveway, a sign of how quickly the patients were evacuated. Gardens are filled with four months and more worth of weeds and the paddy fields are fallow.

A few cattle on the verge were startled by the buses and cantered off into the distance, enjoying their freedom with the farmers gone.

We were going to the town of Okuma. Two busloads of people from there were using their hour-and-a-half or so at home to remember their dead.

It is near the sea and was badly hit by the tsunami, but they had left in such a hurry as the power station just 3 or 4 kilometres up the road was rocked by explosions, that they had little time to commemorate those who were lost.

The people gathered in front of an altar set up on trestle tables in a car park. Freshly ironed white table clothes had been brought, and flowers in bowls and candles.

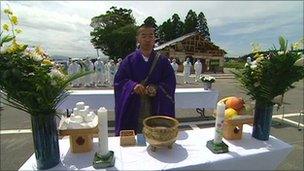

Only the Buddhist priest, chanting and ringing his bell chose not to wear a mask or radiation suit. He was in his purple kimono, his faith his only protection. His prayers competed with the clicking of geiger counters.

"Radiation is invisible, so we are worried," said Shigeru Suzuki, a former resident. "We're wearing these suits because we were told to. This is the only way we can come here. We just have to trust the people who brought us."

Slow rebuilding

The ceremony was led by the mayor of Okuma, Toshiami Watanabe. The community he leads no longer exists, it is scattered in evacuation centres across northern Japan. He admitted being angry with TEPCO, the operators of the Fukushima plant.

Only the priest chose not to wear a mask

"Yes, lots of thoughts are running through my mind," he said. "But we have to rebuild this town in the future and get back to how things were before, or even better."

Rebuilding will have to wait, though, until the nuclear crisis is over. Some progress has been made: phase one of the operation has been completed. A closed system has been installed to clean contaminated, radioactive water at the site, and use it to cool the reactors.

It means they no longer have to be hosed down. The plan is to bring them to a cold shutdown by January at the latest.

But cleaning up around Fukushima could take years. After the memorial service the people of Okuma got back on their buses to be driven out of the exclusion zone.

It may be a long time before they are together again.