Senegal's Mourides: Islam's mystical entrepreneurs

- Published

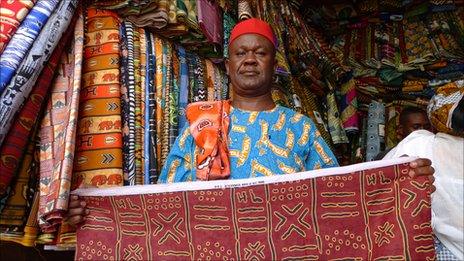

Many of the street vendors commonly seen in Italy, France and Spain selling sunglasses, bags and souvenirs are members of a highly industrious, entrepreneurial branch of Sufi Islam, which has its roots in Senegal.

At the entrance to Touba, Senegal's second-largest city, is a gateway arching over the road under which a sign urges visitors to respect the orders of the local Islamic leader and to not smoke.

Touba, a four-hour drive east of the Senegalese capital Dakar, is the spiritual home of the Mouride Brotherhood, a branch of Islam which holds the sanctity of work as one of its core beliefs. Perhaps this explains why the city is covered in adverts for international banks and money transfer services.

I am taken on a tour of Touba's great mosque by Cheikh Sene, a Mouride scholar from nearby Bambey University.

In a quiet corner of the mosque men sit chatting, while in a nearby room younger men are busy, hunched over computers working on the mosque's website.

A constant stream of people come to the mosque to pay homage at the tomb of Amadou Bamba - a Sufi mystic and founder of the Mouride Brotherhood.

For true believers, says Mr Sene, the path laid down by Bamba is nothing short of "the real practice of Islam". It is also a path of which many other Muslims in the world strongly disapprove.

"They think we are nothing," says Mr Sene, referring to many Arab Muslims, whom he says have done much to rid their own countries and east Africa of Sufi traditions.

"They think we are crazy. They think they are superior."

However, without a flicker of a doubt, he adds that if they come to Touba, "they will be dazzled by the light of Amadou Bamba".

Saint-like status

Following his death in 1927, Amadou Bamba was buried in the then small settlement of Touba, which he founded in 1887.

Watch: Inside the Mourides' grand mosque in Touba, Senegal

Today, Bamba has achieved saint-like status among his followers, and the great mosque, with four towering minarets and a green dome over his mausoleum, has grown and grown.

It can accommodate more than 7,000 people for Friday prayers, and is constantly being improved. When I visited, crates containing air conditioning units sat ready to be unpacked, the gift of a wealthy follower.

Replacement marble slabs, which are cooler on the feet in the heat, were also being laid.

Like the mosque, Touba itself has grown exponentially. Hot and dusty, it is now Senegal's second city, with an estimated population of one million.

But this can double during the Mouride festival of the Grand Magal, which is held early every year, and which can bring more than a million visiting pilgrims on to the streets.

Amadou Bamba's vision of Islam was one which has at its very core the precepts of non-violence and hard work.

Since his death, Touba and the Mouride Brotherhood have been controlled by Bamba's sons, and grandsons, several of whom have held the position of Caliph - the spiritual head of the order.

Out of a population of some 14 million, there are thought to be anything between three and five million Mourides in Senegal.

Famous followers

They include the humblest of peasants to Senegal's now somewhat beleaguered president, Abdoulaye Wade, who has recently faced intense criticism amid recent protests against proposed changes to the constitution.

More than a million Mourides make the pilgrimage to Touba each year

Perhaps the best-known follower of Mouridism is the musician Youssou N'Dour.

When I met him in the television station he owns in Dakar, he talked about his 2004 Grammy award-winning album Egypt, which celebrated Amadou Bamba and Mouridism.

He argues Mouridism is a counter to the post-9/11 stereotype of Muslims. "In the West, you read all about terrorism... we're all lumped together. But those of us who understand that it's a religion of peace, love and sharing mustn't give up.

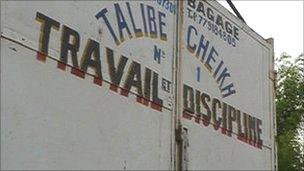

"Mouridism is for me two paths - one is the way to God, the other path is the doctrine of work and dignity. Because if you don't work, you hold your hand out and lose your dignity."

Amadou Bamba was exiled by the French, the colonial power in Senegal during his lifetime. So as well as preaching the virtues of hard work, N'Dour says Bamba inspired his followers to travel.

Of course, like other migrants from poor countries, many Senegalese go abroad because they are looking for work and because they want to send money home to their families, but Mourides have an additional spiritual motivation.

The Mouride motto is "Travail et Discipline" - Work and Discipline

Abroad and at home, Mouridism not only preaches self-help, but also the responsibility to look after others within the Brotherhood.

One of the things that distinguishes Sufism from other branches of Islam is the role of spiritual guides, known in Senegal as marabouts.

These marabouts help their followers make business deals and introduce their followers to important contacts.

After fighting through the choking traffic on the outskirts of Senegal's capital, Dakar, I visit Oumar Fall, the commercial director of Diprom, a major oil and gas firm.

It owns a chain of petrol stations called Touba Oil, whose logo is an image of the tallest minaret of Bamba's mosque.

He tells me that the firm has done well with contacts made through marabouts. Marabouts will even help negotiate and settle disputes, he says.

And if a business deal is successful, a marabout can expect financial compensation, and followers will usually donate money to the Brotherhood.

Political clout

Ninety five per cent of Senegal's population is Muslim, and the vast majority belong to one Sufi brotherhood or another.

Mouridism is the youngest, and said to be the most dynamic, not least because it is organised in a strict pyramid structure headed by the Caliph.

The structures of the others are far more dispersed and thus arguably weaker.

Another reason for the popularity of Mouridism is that it is the only brotherhood founded by a Senegalese. The image of Amadou Bamba is everywhere in Senegal, plastered on car and bus windscreens, in shops and carried in charms around people's necks. Giant portraits of him loom out at you from painted city walls.

But, says Latir Mane, the political editor of L'Observateur, a newspaper owned by Youssou N'dour, many non-Mourides chafe at what they see as the overweening economic and political power of the Mourides.

All politicians he says, even non-Mourides, look for endorsement from Touba because they want Mouride votes.

"Nowadays religion is deeply immersed in politics," he says.

If the Caliph issues an ndigel, or order, all Mourides are bound to follow, says Mr Mane, which gives the Caliph significant political clout.

However, he says, the fact that there are now so many Mourides, whose political interests are not all the same, means that the Caliph's power is less than it would have been in years gone by.

Still, with an aura of success about it, Mouridism is a growing movement and now says Mr Mane, many are joining, not because they believe in it as such, but because they see it as good way to get ahead in life.

You can listen to Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday 4 August at 11:00 BST and Monday 8 August at 20:30 BST. You can also listen via the BBC iPlayer or the podcast.

- Published1 July 2010

- Published9 July 2024