Could Somali famine deal a fatal blow to al-Shabab?

- Published

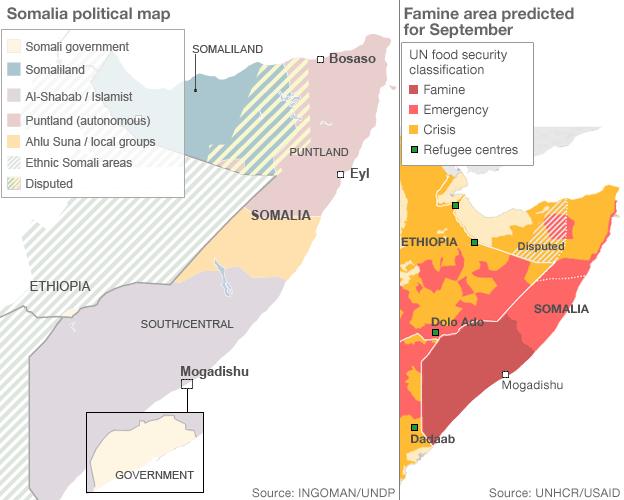

Somalia's militant Islamist group al-Shabab is in crisis, as it battles to cope with the famine that is far worse in areas under its control than other parts of the country, leading to reports of splits in the leadership of the al-Qaeda-linked group.

The famine has forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee the Lower Shabelle and Bakool regions in search of food.

Many are escaping to the capital, Mogadishu, where over the weekend the group made what it called a tactical withdrawal of its forces from the northern suburbs that were under its control.

Others are walking for days to reach camps in neighbouring Kenya and Ethiopia, arch-foes of al-Shabab.

"It is not a good picture for al-Shabab," says US-based Somali journalist Abdirahman Aynte, who is writing a book on the movement.

"Nearly 500,000 people have left. Al-Shabab cannot do anything about it. They have become bystanders."

He says al-Shabab - formed as the youth wing of the now-defunct Union of Islamic Courts in 2006 - had genuine support when it took power in most of south and central Somalia, as people longed for an end to the lawlessness that has gripped the country since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991.

"Even though al-Shabab had draconian laws, they were somewhat popular because of the stability they provided," says Mr Aynte.

"Government areas were not safe - even soldiers were involved in robbing and looting. In al-Shabab areas, you will have your hands amputated if you steal. It was a deterrent. "

Kenya-based Somali journalist Fatuma Noor, who travelled through al-Shabab territory last year, says the famine has damaged the group's credibility.

"Al-Shabab are losing support. People are saying that the drought in the region was caused by a lack of rains, but the famine was man-made. They are asking - why has it been only in al-Shabab's areas?" Ms Noor says.

Taxing charities

She says many Somalis are blaming al-Shabab for the severity of the crisis because of the ban it imposed on the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and some other Western agencies in 2009.

"There have been warnings of a famine since last year, but there was no proper planning to prevent it," says Ms Noor.

But a London-based al-Shabab observer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, argues that the UN blundered by declaring a famine.

He points out that al-Shabab lifted the ban on charities last month; only to reimpose it after the UN's declaration.

Nearly all al-Shabab areas are expected to be hit by famine

"Al-Shabab felt the UN was undermining it; that it wanted to move in and take over. The UN should have concentrated on building trust with al-Shabab and getting aid in to save lives. It didn't matter whether you called it a drought or a famine," he says.

But Mr Aynte accuses al-Shabab of refusing to take responsibility for the crisis.

"It says there is a drought, caused by Allah and people should pray for rain."

He says it is difficult for charities to work with al-Shabab because it demands money from them.

"Al-Shabab are suspicious of aid agencies but 10%-15% of their revenue comes from them.

"Al-Shabab has a humanitarian co-ordination office, which charges a registration fee of $4,000 to $10,000 (£2,400 to £6,000). They also charge a project fee - 20% of the overall cost of digging a borehole or setting up a feeding centre," Mr Aynte says.

The al-Shabab observer who preferred anonymity says the group's leadership is heavily divided over the food crisis - something the UN could have exploited to gain access to starving people.

Al-Shabab's southern leaders - especially Muktar Ali Robow, who comes from famine-hit Lower Shabelle, and Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, who is seen as the elder statesman of Somali Islamists - favour accepting Western aid.

However, they were overruled by the overall leader, Ahmed Abdi Godane, who has led al-Shabab into forging close ties with al-Qaeda.

"Robow's people are directly affected by this famine. So he wants aid agencies to come in. But Godane is suspicious of the UN and doesn't want them in Somalia. So he blocked it," the observer says.

"Robow is now accusing Godane [who hails from the breakaway region of Somaliland] of letting people starve."

Wracked by rivalry

The Somali observer says the famine has worsened divisions between Mr Godane and his rivals.

In June, a top Godane ally, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, who was al-Qaeda's military operations chief in East Africa, was killed at a government roadblock in Mogadishu.

"Fazul was from Comoros and did not know Mogadishu well. Godane is suspicious that his enemies in al-Shabab duped him into going to the checkpoint. At first, government forces did not even know it was Fazul - until they did DNA tests with American help," the observer says.

"It was a big blow to Godane and he became more paranoid. He feels he needs to keep tight control - not open up Somalia to the West."

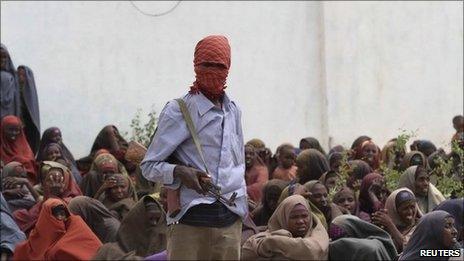

The crisis over the famine comes at a time when al-Shabab - which has between 7,000 and 9,000 fighters - has lost Mogadishu following an offensive by government forces, who are backed by about 9,000 African Union troops.

"Al-Shabab is under pressure. Its moral police [who do not usually fight] are now also on the front line," Mr Aynte says.

The al-Shabab observer said the group announced its retreat from Mogadishu after launching an attack on seven fronts.

"It was a show of unity and force to counter reports that they are weak and divided," the observer says.

He says al-Shabab was unlikely to withdraw completely from Mogadishu. Instead, it would switch to the guerrilla tactics it employed against Ethiopian forces when they invaded the country in 2006 in a failed attempt to defeat the group.

"Al-Shabab never controlled territory at the time. They waged guerrilla war and drove the Ethiopians out."

But the loss of Mogadishu will be a huge financial blow to al-Shabab, as it can no longer extort money out of the businesses in the main Bakara market - the city's commercial hub.

The AU has 9,000 troops in Mogadishu - not enough to patrol the whole city

"Al-Shabab was collecting taxes from about 4,000 shops - from $50 a month from the small trader to thousands of dollars from telecoms companies," Mr Aynte says.

He argues that the famine - along with the military setbacks and financial losses - means that al-Shabab is at its weakest since its formation.

"But it is too early to write it off. Organisationally, it is still intact," Mr Aynte says.

However, UN al-Shabab investigator Matt Bryden believes the group is still financially strong.

"Al-Shabab has evolved from a small, clandestine network into an authority that generates tens of millions of dollars a year," he says.

He also argues that deforestation in al-Shabab-held areas has probably contributed to the famine, as some environmental experts say that cutting down trees can reduce rainfall.

The trees are used to make charcoal, which is exported to Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia, Oman and the United Arab Emirates, Mr Bryden says.

He points out that al-Shabab controls several port cities - including Kismayo, Somalia's second city.

"Charcoal through Kismayo alone is estimated to be worth $15m a year in direct revenue for al-Shabab," Mr Bryden says.

"I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that the scale at which it is taking place is almost industrial."

Mr Bryden says al-Shabab is no longer dependent on foreign funding and has enough money to finance its war chest.

But for many observers the key question is: Will al-Shabab rally to the aid of starving Somalis - or will they continue to flee Islamist areas in search of food?

"I do not think al-Shabab really cares about the famine," says Mr Aynte. "It is more interested in fighting the government and the AU force."